Influenced by the gothic fiction tradition, ghost stories have long captivated audiences and readers, with ghostly beings so often fascinating precisely because of their ability to elude definition: obscurity and intrigue are necessary for the realm of ‘ghostliness’, and set ablaze the imagination as a result. Anything ‘supernatural’ seems at once displaced from yet close to reality, and it is this small shift, similar to Freud’s ‘uncanny’, which is so unsettling. The Victorian era – the supposed ‘golden age’ of the ghost story – lent itself well to the form. Roger Clarke (author of A Natural History of Ghosts: 500 Years of Hunting for Proof) has put this down to a number of reasons – such as it being the era of flickering gaslamps with possible hallucinogenic properties, an era also of large stately homes, with secret passageways for servants to flit through unseen by the guests of the house. This is also an age when representations of reality could be popularly captured through photography, giving rise to ‘spirit photography’ that distorted the reality captured in eerie and, at the time, convincing ways. We’re adding to our range of classic gothic novels with a series on short stories, and today’s blog will take an overview of ghost stories in particular, trying to snatch a glimpse of those many elusive ghosts that have graced pages in history.

Influenced by the gothic fiction tradition, ghost stories have long captivated audiences and readers, with ghostly beings so often fascinating precisely because of their ability to elude definition: obscurity and intrigue are necessary for the realm of ‘ghostliness’, and set ablaze the imagination as a result. Anything ‘supernatural’ seems at once displaced from yet close to reality, and it is this small shift, similar to Freud’s ‘uncanny’, which is so unsettling. The Victorian era – the supposed ‘golden age’ of the ghost story – lent itself well to the form. Roger Clarke (author of A Natural History of Ghosts: 500 Years of Hunting for Proof) has put this down to a number of reasons – such as it being the era of flickering gaslamps with possible hallucinogenic properties, an era also of large stately homes, with secret passageways for servants to flit through unseen by the guests of the house. This is also an age when representations of reality could be popularly captured through photography, giving rise to ‘spirit photography’ that distorted the reality captured in eerie and, at the time, convincing ways. We’re adding to our range of classic gothic novels with a series on short stories, and today’s blog will take an overview of ghost stories in particular, trying to snatch a glimpse of those many elusive ghosts that have graced pages in history.

Feeding Unquiet Spirits

We will start with Shakespeare’s Hamlet (c. 1600) – not a short story, and not even a short play, but it cannot fail to be mentioned here. The ghost of Hamlet’s dead father is the driving force of the story, with its parting words of ‘remember me’ resonating so strongly with the title character that they become an obsession. Throughout, Hamlet is haunted by the past, and he feeds his suspicions by dwelling on that ghostly remembrance. He is perpetually unsettled, and just as ghosts toe the line between tangible and intangible, he is caught in between states: his misgivings urge him to action while his doubts delay that action. The indistinct can linger this way in the mind, and this is a feature that will (appropriately) lurk throughout our exploration of fictional ghosts.

The rise of the periodical press during the Victorian era provided an ideal setting for ghost stories – a regular dose in a manageable length and format, stories like Dickens’s The Christmas Carol (1843) found success this way. Ghosts in this story too are a major influence on the main character, with Scrooge’s behaviour, attitude and perspective altered as a result of his encounter with ghosts. The serial form also encouraged a sense of community, the anticipation for the next installment building hype, and we will see how ‘feeding’ ghosts is an important technique at play within ghost stories themselves. Having its roots in an oral tradition, such stories were shared to pass the time round a campfire, the sense of community creating the atmosphere as much as the words. Washington Irving’s The Legend of Sleepy Hollow (1820) is a good example of how ghostly settings are encouraged, with belief in the headless horseman fed through legend and the villagers’ excitable speculations. The best ghost stories are often shaped this way – reality is pieced together through different accounts, information is incomplete, an accurate picture cannot be formed, and the mystery and suspense is thereby preserved.

A Guilty Conscience

Ghosts feature in another of Shakespeare’s plays, haunting and tormenting the protagonist in a similar fashion: in Macbeth (c. 1606), his guilt manifests itself in the ghostly figures that he sees at the banquet – the fact that no other characters can see them establishes these ghosts as personal ones, ultimately leading to his inability to distinguish reality from unreality. We need only bring to mind the oft-quoted ‘Is this a dagger which I see before me?’ or the blood on Lady Macbeth’s hands to observe the terror of such hallucinations. In this case, the unsettled soul, or ghost, is the ‘observer’, in whose trapped state of mental anguish the ghost becomes a displaced vision of themselves, their acts, their past. We touched on The Strange Case of Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde (1886) in the last blog, but it also deserves a mention here, if only to see this identity split in action: because they are so different in ‘character’, Jekyll and Hyde are regarded as separate identities for much of the book, with Hyde a ghostly, menacing and monstly figure to observers because his true identity cannot be pinned down. We also mentioned Poe in our last blog, and his relevance is just as strong here, as an author that detailed the psychological mechanisms behind guilt. The Tell-Tale Heart (1843) is a brilliant example of this, where a murderer is driven insane by what he believes is the sound of his victim’s heart still beating beneath the floorboards. The seemingly rational voice of the narrator exercises what M R James identified as one of the key aspects of a ghost story: ‘the pretence of truth’. We are trapped in the narrator’s ineffectual grasp on reality, and though not a ‘visual’ ghost in this case, his past actions haunt him with increasing intensity and just as effectively.

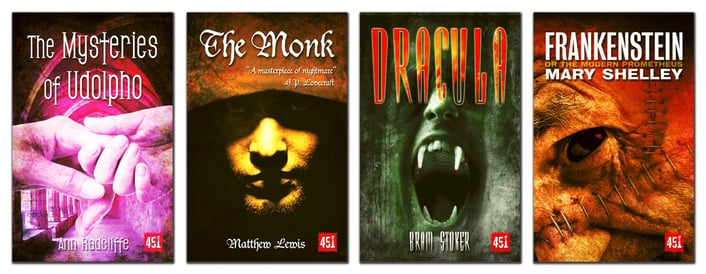

Take a look at our Gothic Horror titles by clicking here

Tricks of the Mind

Sheridan Le Fanu was another Victorian writer with a wealthy collection of ghost stories. His short stories served as preparatory material for his longer novels, and relied on the strength of the implied, always leaving things open-ended and avoiding any explanation as to the ‘reality’ of his ghostly figures. The evil monkey in his short story Green Tea (collected in his 1872 anthology In a Glass Darkly), for example, is invisible to all other characters and could be explained as a hallucination – with no explanation that it is ‘just’ a delusion, however, the mystery lingers long after the story ends. Henry James’s The Turn of the Screw (1898) operates in a similar way, and has been all the more terrifying and successful for it. He weaves the sinister elements gradually into the governess’s account, and trapped in this particular viewpoint, the reader never receives confirmation of either the unreliability of her account or the reality of the supernatural figures she witnesses.

M R James is another landmark in the history of the form, with his vast body of works effectively defining the ghost story style during the 20th century. Taking "Oh, Whistle, And I'll Come To You, My Lad" (1904) as an example, the tension is built up through unclear connections (the role of the whistle in summoning spirits, the animation of the bed sheets) – it is again a want of explanation that fuels the intrigue, and the creepiness. M R James was a keen user of malevolent ghosts, negative forces actively seeking to terrify. Oscar Wilde’s ghost in The Canterville Ghost (1887) provides a comic take on this, where the theatrical ghost Sir Simon, despite his best efforts, fails to scare the family who’ve just moved into the house he haunts. His own tricks are turned back onto him, reversing the role so that the ghost is the one that is terrorised, weakened and frightened. The tone is humorous, but the ghost is nevertheless in a state of entrapment – he can only be released through a specific form of closure. The lack of closure enables such ghosts – in the mind or otherwise – to persist.

Hauntings and Obsessions

Ghosts in their most insubstantial form can be simply ideas and memories that haunt their subjects just as effectively as visions. Though there are too many examples of this form of ‘ghost’ to list here, a particular one to mention would be any in Ibsen’s Ghosts (1881). Just as in Hamlet, echoes from the past lead the action in this play, with the ghosts being the residual repercussions of past deeds that bubble beneath the surface – the sinister re-emergence of events or genetic traits incorrectly believed to be long-gone. This play in particular details a fear (and denial) of such ghosts being aired, as characters battle to stop being haunted by the past. The dissolution of ghosts, however, is often the only way for ghost stories to truly end: only when ghosts are ‘laid to rest’ can they be transformed from their ‘ghostly’ intangible identity into something that can be dealt with and understood. Again, therefore, we can see ghosts as influencing background forces, not fully understood and so inhabiting a strange supernatural state.

The short story format lends itself well to the nature of ghost stories – brief, engaging, not quite enough room to paint a full picture but space enough to allow mystery to breed. It seems that there has been not so much a development of the form in the history of the genre, but rather a variety of ways in which ‘ghosts’ have been used as a device to indicate obstructed clarity, and so encourage suspense and intrigue.

Although not a short story, Daphne du Maurier’s Rebecca (1938) contains many of the elements mentioned above. The story chronicles the plight of a second wife stepping into the shoes (and inhabiting the house) of a deceased first wife. The second wife sees echoes of the first wife in everything, feels her presence everywhere, and is haunted by the memory of the first wife. Her torment is fuelled by the sinister figure of the housekeeper Mrs Danvers, whose own obsession and ghostly influence keeps the first wife very much alive. Through all these examples, the ‘ghosts’ show themselves to be powerful precisely because of their lack of substance: they succeed in being chilling through their closeness to reality, yet prolong suspense in their inability to be fully explained. As Susan Hill’s terrifying novella The Woman in Black (1893) has shown, the supernatural continues to disturb and unsettle, to engage and thrill the imagination.

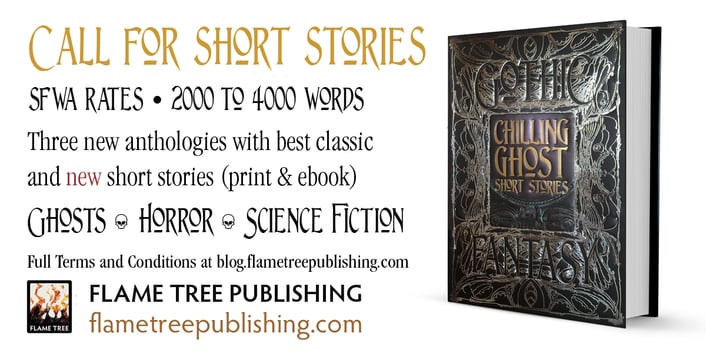

Watch out for our next installment in this series of blogs, which will explore the origins, influences and developments of Science Fiction. Right now, we’re looking for short story submissions for our upcoming anthologies covering Ghosts, Horror and Science Fiction. Take a peek here if you'd like to find out more!