Author of ‘Rip Van Winkle’ (1819) and ‘The Legend of Sleepy Hollow’ (1820), Washington Irving (1783–1859) holds a great place in the canon of American short story writers. A leading author of early American gothic horror alongside Poe and Hawthorne, he was also a witty commentator and prominent literary figure in the New York public eye. Writing during a period when literary communities and publications were beginning to sprout up all over, Irving incorporated his keen knowledge of human society and relationships into his work. The dialogues between and within art forms that were happening at this time helped fuel various literary movements into existence, where writers would communicate openly, shaping each other’s works and accelerating the development of their ideas and careers. In this post we’ll be taking a look at the emergence and impact of these literary communities, and Irving’s place in this larger process. We’ll also explore some of Irving’s inspired marketing techniques and see how we have him to thank for bringing the words ‘Gotham’ and ‘Knickerbocker’ into common usage!

Author of ‘Rip Van Winkle’ (1819) and ‘The Legend of Sleepy Hollow’ (1820), Washington Irving (1783–1859) holds a great place in the canon of American short story writers. A leading author of early American gothic horror alongside Poe and Hawthorne, he was also a witty commentator and prominent literary figure in the New York public eye. Writing during a period when literary communities and publications were beginning to sprout up all over, Irving incorporated his keen knowledge of human society and relationships into his work. The dialogues between and within art forms that were happening at this time helped fuel various literary movements into existence, where writers would communicate openly, shaping each other’s works and accelerating the development of their ideas and careers. In this post we’ll be taking a look at the emergence and impact of these literary communities, and Irving’s place in this larger process. We’ll also explore some of Irving’s inspired marketing techniques and see how we have him to thank for bringing the words ‘Gotham’ and ‘Knickerbocker’ into common usage!

Early Days

Born to a large family, and named after George Washington, Irving is widely understood to be the first American Man of Letters: a medium of writing that we shall see proved advantageous to an author’s public success during this period. He was also one of the first people to be able to live successfully off his earnings as a writer, being a celebrated author in both America and Europe during his lifetime. A visit to Sleepy Hollow inspired the setting for his hugely popular tale, and later on in his life he owned a house (‘Sunnyside’) in the nearby village Tarrytown, where he hosted many of his literary fellows including Charles Dickens and his wife on their American trip in 1842. Irving was a traveller, with a very active social life and close connections to a number of other notable literary figures.

Early on in his life, Irving wrote satirical comments on society in the form of letters to the New York Morning Chronicle, and he went on to write many more essays, letters, histories and biographies – this latter collection included subjects like George Washington, the writer Oliver Goldsmith and the Islamic prophet Muhammad. He was writing during an incredibly formative period, when the short story was developing into an art form, and literary magazines were appearing all over. At the start of the nineteenth century, Irving was very much at the start of this process, playing a key role as various literary movements – the short story, and by extension the gothic short story – were gathering speed, facilitating this process as much as being a part of it. To put this into perspective: Irving’s major work, ‘The Sketch Book of Geoffrey Crayon, Gent.’, a collection of short stories and essays including 'Rip Van Winkle' and 'The Legend of Sleepy Hollow', was published between 1819 and 1820. Nathaniel Hawthorne’s first tales were published around 1830, and Edgar Allen Poe’s first tale wasn’t published until 1832, with ‘his’ era being the 1840s. 'The Sketch Book' was hugely popular in America and Europe, and inspired many other sketches and tales of its kind. The development of the American Short Story during the nineteenth century reflected the changes that were happening across the continent: the very speed of life in America was changing, with people frequently moving from city to city looking for economic opportunities. The short story format and the accessibility of newspapers that featured them suited this mode of life, and the many literary magazines that were set up during this period encouraged the form as well and strengthened communication between the writers.

Making a Name

In the first decade of the nineteenth century, Washington Irving set up his own literary periodical: Salmagundi. He wrote the satirical magazine along with his brother William Irving and James Kirk Paulding, who with Irving was part of a social group that nicknamed themselves 'The Lads of Kilkenny'. Humorously ridiculing New York culture, they wrote under pseudonyms like William Wizard, Launcelot Langstaff and Pindar Cockloft, stating their purpose as to ‘instruct the young, reform the old, correct the town, and castigate the age’. It is in this publication that Irving appropriated the nickname ‘Gotham’ for New York City, which has since stuck in popular culture.

Using pseudonyms was a common technique for Irving, and it proved to be an interesting marketing advantage as well as an acute observation on the workings behind celebrity culture. His first major book, A History of New York (1809), was a burlesque account penned by ‘Diedrich Knickerbocker’, a character that would also go on to narrate 'Rip Van Winkle'. For A History of New York, Irving undertook an ingenious advertising campaign centred on building mystery and intrigue around this ‘Knickerbocker’ fellow, in particular spreading the idea that this ‘dutch historian’ had gone missing from his hotel in New York City, leaving his book manuscript behind. Irving placed a number of missing person adverts in local newspapers and included a notice from the hotel's fictional owner stating that if Knickerbocker did not return and pay his bill, the owner would publish the manuscript. This brought the eager public eye to his book, which was as a result hotly anticipated before its publication. Moreover, Knickerbocker kept cropping up as a public figure, featured ‘in conversation’ in the early issues of the monthly magazine the Knickerbacker, which then changed its name to the Knickerbocker. Founded by Charles Fenno Hoffman in 1833 and with over 30 years of publication, it was hugely popular as one of the first publications that paid its contributors. This attracted great names (and therefore readership) to the magazines, as well as inspiring many more of its kind. In fact, by 1840 (while Irving was one of its staff writers), it was the most influential literary publication, with a circle of contributors including Henry Wadsworth Longfellow, James Russell Lowell, Oliver Wendell Holmes and James Fenimore Cooper. Irving knew already that it was the author as much as the story that brought success. This adds a very commercial aspect when appreciated with regard to short stories at this time, as having your story featured in a newspaper began to pay quite well. Such stand-alone tales became a very marketable product, with it being advantageous for writers to establish themselves as a ‘name’ and build a sort of brand. This was, in effect, the beginnings of nineteenth century networking, where communities of writers would open doors for one another, challenging and inspiring each other and keeping themselves in the public gaze.

Washington Irving (right) and His Literary Friends at Sunnyside, 1864 Image source

A Sense of Community

The Knickerbocker group was an effective band of brothers: lending each other money and making efforts to get each other’s manuscripts taken by particular publishers. Each person made use of their individual contacts to help others, who would then help them in turn. This brings us to the world of letters, and of public communication, which branched out from the New York writers to form an intricate network of contacts, opportunities and inspiration. The idea of literary circles was not a new one, but it easily took hold during this period. The English equivalent at the time involved Dickens, George Eliot and Thackeray, and also Mary Shelley’s travelling circle of acquaintances. Such circles continued to form in the twentieth century – an example being Virginia Woolf and the Bloomsbury set. Back in Irving’s time though, this was a flourishing concept, these very public relationships where writers would comment on each other’s work, drawing attention to both themselves and their fellow writers as they did so – indeed, the public mind soon easily associated Thoreau and Emerson together, as it did with Hawthorne and Melville. There was a sort of commerce within these circles, where the exchange of ideas propelled their careers – and literary production – forward, in a kind of symbiotic relationship. It was believed at the time that collaboration was in this way more effective than individual venture; it was socially and economically advantageous to have someone to discourse with as it permitted an author to have a public presence. These mutually beneficial affiliations granted each member professional support and intellectual stimulation, so artists and writers stood to gain a lot from this form of creative collaboration. Irving, again, was writing in the early days of these blossoming communities: Poe, back then a budding young author, would come to Irving for advice, asking for literary guidance on 'The Fall of the House of Usher' and other of his works. Irving’s Knickerbocker days established a lasting community of writers that served as each other’s support, inspiration and encouragement; when Irving died, Longfellow commemorated Irving’s grave and legacy in an 1876 poem entitled ‘In the Churchyard at Tarrytown’.

Gothic Elements

We’ve already written a blog on why short stories were so well suited for the emergence of ghost stories, though it has become apparent here that other aspects of literary development could have inspired and encouraged the popularity of gothic short fiction during this period. Irving was a master of satire, and his understanding of people and gossip fuelled his marketing plans as well as the content of his work. ‘The Legend of Sleepy Hollow’ is a prime example: its subject is a ‘legend’, predicated on an atmosphere of superstition, mystery and gossip. In the story the narrator describes ‘the witching influence of the air’ in the area, and it seems this breeding ground for the imagination is one that Irving, involved in an era of connections, publicity and reputation, was only too familiar with. His use of various personas, such as Geoffrey Crayon and Diedrich Knickerbocker, were a way of disassociating himself from the story, allowing a further layer of commentary and amplifying the ability of a story to hold intrigue: Poe also ‘concealed’ the true author of many of his tales, and Hawthorne too would use a ‘story within a story’ technique to blur the facts of a tale’s provenance, and so augment its mystery and potential for horror.

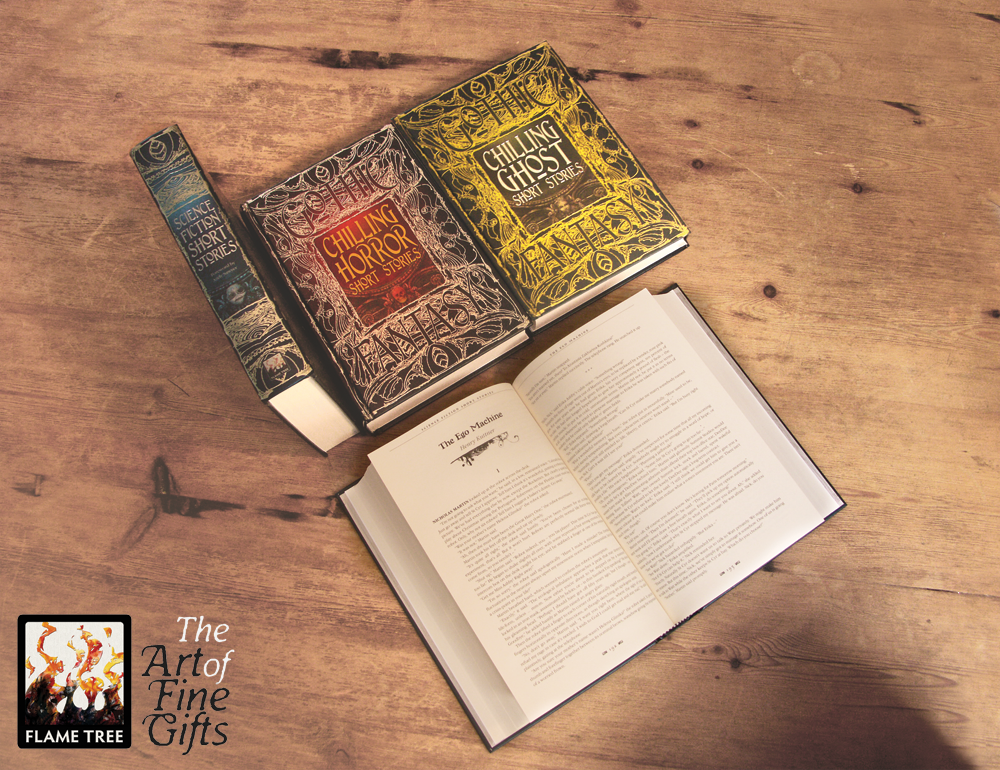

Our new Gothic Fantasy Anthologies feature short stories by a range of new and classic authors, including Hawthorne, Poe and Irving. ‘The Legend of Sleepy Hollow’ appears in our beautifully bound Chilling Ghost Short Stories, which you can buy right now through our website or via Amazon.

LINKS

- We have two other anthologies as part of our Gothic Fantasy series: Chilling Horror Short Stories, and Science Fiction Short Stories.

- Have a look at Washington Irving's historic home 'Sunnyside'.

- Learn more about the history of the Knickerbocker, and it's development into 'Knickers', here.