Inspired by the RA’s new exhibition on Painting the Modern Garden, of which Monet’s stunning Garden of Giverny paintings are a big part, this blog takes a look at one of the most popular art movements: Impressionism. We put it into context – with a brief look first at Realism in France, and its move away from classical art; as well as an exploration into how it formed the roots of Post-Impressionism.

Naturalism and Realism

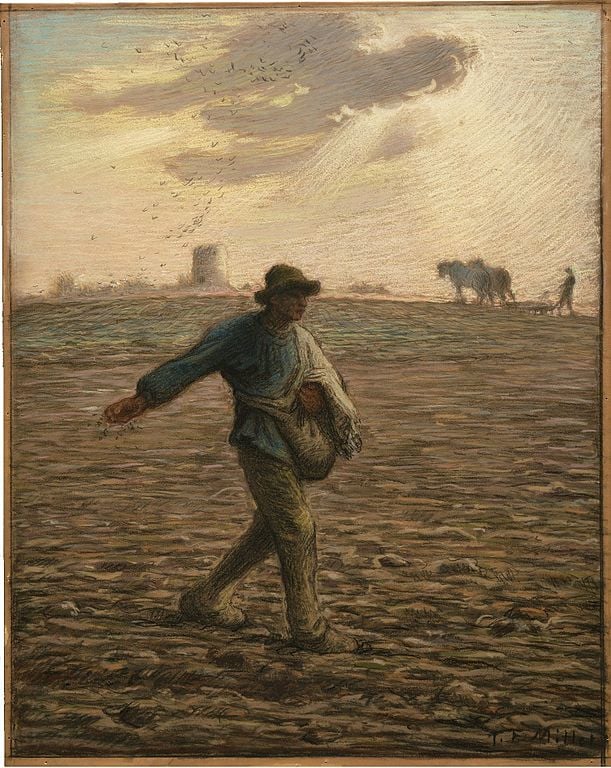

The artist Jean-Francois Millet (1814–75) came from a peasant background and grew up with an appreciation of nature, while living and working with his father on a small farm. His paintings of peasant subjects broke new ground and triggered a movement in France that combined naturalism with realism in order to make a statement with political undertones. France in the period of the Second Empire was still coming to grips with industrialization and the drift of the peasantry from the land to the burgeoning industrial towns. It was a period of great deprivation and social injustice. What Emile Zola and Victor Hugo achieved through their polemical novels, artists such as Gustave Courbet (1819–77) and Honoré Daumier (1810–79) sought to create through their paintings.

A Social Commentary

Courbet believed that the common people were the only true custodians of real values and simple truths, a viewpoint perhaps that comes across very vividly in the vigour and passion of his pictures. Not surprisingly, Courbet was severely criticized and reviled for coarseness and vulgarity when his paintings were exhibited at the Salon. Undaunted, Courbet persevered, and his later canvases became even more dedicated to putting across his notions of primitive socialism. True to his principles, he took an active part in the ill-starred Paris Commune of 1870–71.

Daumier went much further, neatly avoiding the cloying sentimentality that occasionally reduced the paintings of Camille Corot (1796–1875) and Millet to mawkishness. His chief forte was the lithograph, a medium that he used extremely effectively to put across his satirical and often savage comment on the ills of society. After the Revolution of 1848 he took up painting, and became increasingly strident in his attacks on the corruption and hypocrisy of the bourgeoisie after Louis Napoleon seized power. He was too satirical to be regarded as a Naturalist, but his use of Realism as social comment has never been surpassed.

Impressionism

The breakthrough of Realism and Naturalism over the classical tradition paved the way for a new style of art that would come to be known as Impressionism, which depicted similar subject matters of landscapes and contemporary life but with a looser, more emotive style.

Evolution of a new Style

Although the term ‘Impressionism’ did not come into use until 1874 when Claude Monet (1840–1926) exhibited a painting entitled Impression: Sunrise, Le Havre (see left) – provoking the comment by Louis Leroy that pictures of this kind were an ‘impression’ of nature, nothing more – the movement had been evolving for more than a decade. Camille Pissarro (1839–1903) had been a pupil of Corot, whose open-air landscapes pointed the way towards Impressionism. Edouard Manet (1832–83) had been influenced by Goya, whereas Edgar Degas (1834–1917) had studied under Ingres. Alfred Sisley (1839–99), Claude Monet and Pierre-Auguste Renoir (1841–1919) were among the other leading figures. While they were primarily preoccupied with landscape, Renoir became one of the leading exponents of the female nude, while Manet excelled in animated groups and Degas was renowned for his paintings of ballet dancers.

Claude Monet

Claude Monet was a key founding member of the Impressionist circle – as mentioned above, it was one of his paintings that gave the group its name. He was born in Paris, but grew up on the Normandy coast, where he developed an early interest in landscape painting. His early mentors were Johan Jongkind (1819–91) and Eugène Boudin (1824–98), and the latter encouraged Claude to paint outdoors rather than in the studio. This was to be one of the key principles of Impressionism.

While a student in Paris, he met Pissarro, Renoir and Sisley, and together they formulated the basic ideas of the movement. They staged their own shows, holding eight exhibitions between 1874 and 1886. Initially these attracted savage criticism, causing genuine financial hardship to Monet and his friends. His most distinctive innovation was the ‘series’ painting. Here, Monet depicted the same subject again and again, at different times of the day or in different seasons. In these pictures, his real aim was not to portray a physical object – whether a row of poplars or the façade of Rouen cathedral – but to capture the changing light and atmospheric conditions.

Impressionist Techniques

It was the Impressionists who began exploring new ways of working oils on canvas. Claude Monet was the arch exponent of this style, who succeeded in conveying the illusion of spontaneity, the image captured at a single moment in time. Obviously the actual execution of any painting, however rapidly it is carried out, takes more than a few moments. The secret lay in the preparation of the groundwork. Monet used a fine-weave canvas with a thin basic wash, on top of which he painted broad areas in two or three basic colours. Next he applied opaque paint in patches which allowed a glimpse of the underlying blocks and then used a wide variety of different brushwork, putting fresh paint on still-wet surfaces or dragging pure, almost dry paint, across the surface to create special effects and textures, often by using the wooden point of his brushes to let the pale ground show through. The resulting variety of colours and the scintillating play of light and reflection give his canvases their instantaneous character.

The Impressionists in general made extensive use of wet-on-wet techniques to soften the edges of contrasting colours, or softened the lines by rubbing them or painting over them with a thin opaque coat of colour – a practice known as ‘scumbling’. Pierre-Auguste Renoir was the first painter of his generation to explore the potential of warm-cool colour contrasts which he used to great advantage in his nude studies. He also employed rubbing and staining to build up form, colour and depth.

Post-Impressionism

On the fringe of Impressionism was Paul Cézanne (1839–1906), who felt uneasy at the lack of discipline in this style and wished to return to a greater reliance on form and content without sacrificing the feeling for light and brilliant colours. Out of this evolved Post-Impressionism, a term that originally meant merely ‘after Impressionism’, but which became the springboard to all the varied ‘isms’ that come under the heading of modern painting.

The Main Players

Apart from Cézanne, the leading Post-Impressionists included Georges Seurat (1859–91), an early practioner of Pointillism, the technique of applying small strokes or dots of pure colour so that from a distance they appear to blend together. Neither of these artists were particularly concerned with the emotional content of their paintings, but this was the principal feature of the works of Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec (1864–1901), Vincent van Gogh (1853–90) and Paul Gauguin (1848–1903).

Post-Impressionist Techniques

In the second half of the nineteenth century, scientists like James Clerk Maxwell studied the physical properties of light and colour and painters followed these developments closely. One of these was Georges Seurat who, in 1884, adopted a palette of 11 colours arranged in the sequence in which they appear across the spectrum, from raw sienna to yellow ochre, combined with white to enhance the effects of light. He strove for an opaque impression and deliberately left his paintings unvarnished to heighten the matt effect.

Taking his interest in the composition of colour to its logical conclusion he began in 1885 to build up different hues using patterns of dots. Whereas traditionally artists had mixed yellow and blue pigments to produce shades of green, Seurat aimed at the same effect by placing dots of yellow and blue paint in close proximity, varying the intensity of the colour accordingly. The result, however, was seldom as he intended, for he failed to realize that the eye picked up the signal as a fusion of pigment rather than a blending of light. Camille Pissarro was the other ardent practitioner of Pointillism, but in his case it proved to be an extremely laborious way of achieving subtle shades.

Conclusion

Thanks to those artists who had begun to depict realistic modern life as opposed to always looking back to the past, the groundwork for the new artistic style of Impressionism was born. Artists such as Monet – originally ridiculed but later establishing their presence as founders of one of the definitive art movements of the nineteenth century – captured modern subject matter by embracing colour to express form and mood. Their innovations in light and colour also laid the foundations for Post-Impressionism. We'll learn in another post about the further exploration of colour of modern art, as well as the fascinating influence of the invention of photography.

If you're feeling inspired by Impressionism and want to learn more, our beautiful illustrated book Claude Monet: Waterlilies & The Garden of Giverny (ISBN: 978-1-78361-607-7) is available on our website here; or why not treat yourself to a luxury journal with post-Impressionist masterpiece Starry Night by Van Gogh on its cover, available here.

Links

- Click here for more info about the RA exhibition.

- Julian Beecroft, author of our very own book Claude Monet: Waterlilies & The Garden of Giverny has written a fascinating article for The Telegraph. See it here.

- The Tate offers a great introduction to Impressionism here.