The twentieth century saw many radical changes in people’s lives: an increased pace of technological and industrial change; the rapid spread of large urban centres; the development of new means of transportation and communication; innovative scientific discoveries such as the X-ray and the theory of relativity; the growth of consumerism on a large scale; and the chilling reality of mass warfare. Against this background of social, political and technological developments, Western art also underwent a series of radical shifts.

Art Nouveau

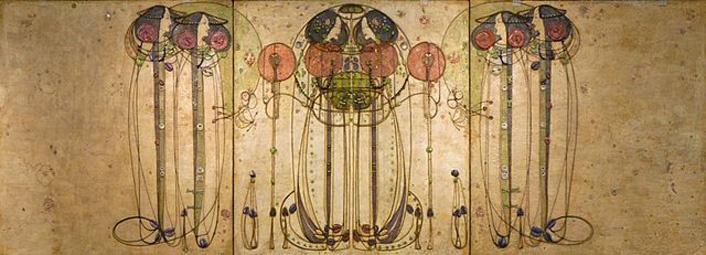

French for ‘new art’, this term was used in the English-speaking world to describe a style that came to prominence in about 1895 and continued until the First World War, being derived from the Paris shop of that name opened by the Hamburg entrepreneur Samuel Bing. Paradoxically, in France it was generally known as le style anglais and in Italy more specifically as lo stile Liberty, after the London department store which did so much to promote it. In the German-speaking countries it was Jugendstil (‘Youth Style’).

Natural, Flowing Lines

All of these names embraced a style distinguished by its sinuous curves, swirling lines and ethereal quality. Figures were elongated and in some cases distorted and its practitioners relied heavily on plant forms; tulips, lily pads and thistle heads being particularly favoured. It manifested itself in every medium of the applied and decorative arts, from the architecture of Antoni Gaudi (1852–1926) and Victor Horta (1861–1947) to the furniture of Charles Rennie Mackintosh (1868–1928) and the Wisteria glass of Tiffany. In the fine arts it was manifest in the drawings of Aubrey Beardsley (1872–98), and the paintings of Edward Burne-Jones (1833–98), Alphonse Mucha (1860–1939) and Jan Toorop (1858–1928). Art Nouveau gave birth to new and exciting interpretations of Modernism that were expressed in the Art Deco movement and the work of Bauhaus.Aubrey Beardsley

Aubrey Beardsley was an English graphic artist, the epitome of fin-de-siècle decadence. Born in Brighton, Beardsley was a frail child and suffered his first attack of tuberculosis in 1879. He left for London at the age of 16, working initially in an insurance office, while attending art classes in the evening. In 1891 Burne-Jones persuaded him to become a professional artist and, two years later, Beardsley received his first major commission, when J.M. Dent engaged him to illustrate Malory’s Morte d’Arthur. The success of this venture gave him the opportunity to work on an even more prestigious project, the illustration of Wilde’s ‘Salome’, while also producing images for a new journal, The Yellow Book.

Soon Beardsley developed a unique style, combining the bold compositional devices used in Japanese prints; the erotic, sometimes perverse imagery of the Symbolists; and an effortless mastery of sinuous, linear design, which prefigured Art Nouveau. A glittering career seemed to beckon, but in 1895 the scandal surrounding the Wilde

trial led to his sacking from The Yellow Book. His tubercular condition flared up again and within three years he was dead.

Futurism

‘Dynamism’ was one of the names considered by the Italian writer Filippo Tommaso Marinetti (1876–1944) for a new movement which he planned to establish; he eventually opted for ‘Futurism’, which also suggested his fascination with the technology and speed of the modern world. Futurism was the first major twentieth-century art movement to be launched explicitly through a series of written manifestos, sets of ideas which preceded the development of new ways of painting.

A Passionate Manifesto

Marinetti lived and worked in Milan, but he published his ‘Founding Manifesto of Futurism’ in French on the front page of Le Figaro in February 1909, as he wished to make an impact upon Paris, still the most important centre for art in Europe. This manifesto was a passionate and provocative attack on culture and tradition, calling for the destruction of museums and libraries and for the glorification of rioting crowds, violent revolutions and war. Beauty in this period, for Marinetti, was to be found in the products of modern technology and industry, and above all in speed, and he claimed that a car was superior in this respect to one of the Louvre’s most prized and famous antique statues: ‘a screaming automobile that seems to run on grape shot, is more beautiful than the Winged Victory of Samothrace’. The exaggerated rhetoric of the Futurist manifestos was an important part of their aim to raise the maximum publicity for themselves, and to communicate their ideas to as wide an audience as possible.

Key Artists

The Futurist group included the artists Umberto Boccioni (1882–1916), Giacomo Balla (1871–1958) and Carlo Carrà (1881–1966), who were involved in a series of widespread publicizing events. Futurist evenings were staged, which could include the showing of paintings, the reading of manifestos, theatrical sketches or the painter Luigi Russolo (1885–1947) playing his cacophonous ‘Noise Machines’. These evenings would often begin with the Futurists hurling insults at their audience, and sometimes ended in brawls and street fights, reported – to their delight – in the press the following day. Between 1912 and 1914 an ‘Exhibition of Futurist Painters’ toured extensively, from Paris via Berlin and London to Chicago and Moscow, accompanied by a series of lectures and publications.

Futurist painting was just one part of an overall assault on the art world, and was intended above all to illustrate ideas laid out in Futurist manifestos. Boccioni’s ‘Technical Manifesto of Futurist Painting’ of 1910 sought to overthrow the art of the past, and described the swift succession and perceptual overloading of images of the modern world that this new art should strive to capture: galloping horses which appeared to have 20 legs; hurtling trams that seemed to merge with the houses around them; the human body becoming part of the furniture on which it is sitting. Balla’s Dynamism of a Dog on a Leash (1912) drew upon time-lapse photography to evoke the successive movements of a woman walking a small dog. Boccioni’s The Street Invades the House (1911) showed a woman leaning from a balcony, her form merging with the tumultuous activity in the street below.

Futurist Techniques

Futurist painters used vibrant colours, thrusting diagonals and energetic, swirling compositions in order to convey speed and movement. They drew upon painterly techniques that had already been established in the late nineteenth century, such as the principle of colour divisionism, a variant of Pointillism, as well as taking inspiration from Cubism. The faceted appearance of Futurist works, where the subject represented began to disappear beneath an overall pattern of shifting planes, and the use of lettering in the work of Carrà and the Paris-based Gino Severini (1883–1965), both derived from Cubist painting. To some extent Futurist painting could not live up to the strident requirements of its manifestos, and it relied more on other artistic developments than may have been intended.

Vorticism

The impact of Cubism and Futurism was felt in many European countries, and in Britain just before the First World War the dynamic treatment of the forms of the modern world found expression in the works of the Vorticist movement. The Futurist Boccioni had stated that all art should find its source in what he called an ‘emotional vortex’, and this terminology was taken up by the poet Ezra Pound (1885–1972) to describe a kind of imagery which would not be flat ‘surface art’, but ‘a Vortex, from which, and through which, and into which ideas are constantly rushing’.

A Brutal Energy

The paintings of Wyndham Lewis (1882–1957), the central figure of Vorticism, are a good illustration of Pound’s definition. Lewis used simplified angular forms suggestive of cityscapes in his compositions, arranged in such a way as to create the impression of plunging recessions and vertiginous depths. Edward Wadsworth (1889–1949) painted abstracted intersecting shapes of buildings, while David Bomberg (1890–1957), an associate of the group, fragmented his motifs, initially based on groups of moving figures, into a brightly coloured overall grid-like pattern. Bomberg’s paintings were the most radical in appearance: In the Hold (1913–14) was made up of a myriad of jostling flat triangles of colour, its original subject matter indicated only by its title. Vorticism crystallized around the publication of the periodical BLAST, which appeared in two issues in 1914 and 1915, and which proclaimed the aim of these artists was to overthrow the legacy of Victorian Britain in an aggressive and violent way. The brutal energy that was one of Vorticism’s central principles, along with its interest in machine technology, strikingly prefigured the mass warfare that brought the movement to an abrupt end.

Bauhaus

Largely a reaction against the florid, fussy styles in the applied arts of the late nineteenth century, the Bauhaus style developed in the early twentieth century under the inspiration and guidance of Walter Gropius (1883–1969), a German architect and designer who was influenced by the writings of John Ruskin and William Morris. Unlike these mentors, he did not reject mechanization but sought ways of harmonizing industrial methods to design. He was appointed Director of the Grand Ducal schools of art in Weimar in 1919, collectively known by the name Bauhaus (literally ‘architecture house’). Gropius and his colleagues strove to marry form and function in the applied arts, architecture and industrial design.

When the Nazis came to power Gropius and his disciples went to France, Britain and the USA, spreading the gospel and laying the foundations for the clean lines of modern industrial design. Paul Klee and Wassily Kandinsky were among the artists who taught at the Bauhaus and were, in turn, imbued with its concepts, leading to the development of Abstract art (which we’ll look at in another Art Movements post).

Art Deco

Art Deco

In the decorative arts the ideas of those at the Bauhaus influenced the development of Art Deco and Art Moderne in the 1920s and 1930s. Similarly The Futurists’ vision also played a part in creating a clamour for the edgy, streamlined Deco style. Art Nouveau, which celebrated the dawn of a new era, had also played a part in the evolution of the Art Deco movement, having sought to create aunifying force in the applied arts. Art Deco absorbed this aesthetic unity of design but employed different styles and techniques to achieve its aim: decorative effects were well designed and more geometric; less sinuous and flowing. However the main unifying factor – as with all the styles mentioned above – was the embrace of modern influences.

If you're feeling inspired by the art discussed here, why not take a look at our stunning Tiffany Magnolia Tree foiled pocket journal available here or our Aubrey Beardsley luxury journal here. If you're a fan of Art Deco our Erté Starstruck foiled journal is a winner.

Links

- This article takes a look at Art Nouveau and Art Deco

- Visit The Tate website for more about Futurism

- The Met Museum offers more insight into The Bauhaus here