Byzantine Art

As the Roman Empire pushed farther east it came in contact with the arts of the Orient and, after the collapse of the empire in the West in the fifth century, the Byzantine Empire increasingly looked to the East for both the form and content of its art.Eastern Influences

Silk-weaving, ivory-carving and glass mosaics all benefited from this Oriental influence. The sumptuously coloured illuminated manuscripts from the sixth century onwards, replete with gold leaf, reflect the influence of Persia, but it was not until the end of the ninth century that representational art, in the style of the Classical Greeks, was revived and then rose to new heights. Most of the surviving examples from the later Byzantine period are associated with imperial portraiture or the representation of saints, out of which developed the tradition for icon painting which continues in Orthodox countries to this day.

The western Roman Empire disintegrated under the incursions of the Goths, Vandals and other barbarian peoples, but while its civilization was destroyed, it did not vanish completely. Western Christianity, with its headquarters in Rome itself, was eventually embraced by the pagan tribes, and from this developed the petty kingdoms of the Dark Ages and the revival of empire under Charlemagne. Italy was reconquered (or liberated) by the Byzantines in the sixth century and in the ensuing period Ravenna and Venice became major centres of Byzantine art and architecture, noted for their religious mosaics.

Although the Byzantine Empire briefly extended along the southern shores of the Mediterranean as far as Morocco, the rise of Islam in the seventh century gradually forced it back and Constantinople itself came under attack in the eighth century. Nevertheless, the Byzantine Empire endured until 1453, when its capital Constantinople fell to the Osmanli Turks. Its art had become somewhat stereotyped and what fresh impetus it had seems to have come from southern Russia (notably in the shape of icons), Turkey or Syria; but from the early 1300s there was a late flowering of Byzantine art, reflected in religious wall-painting, illuminated manuscripts and icons that, in turn, had a dramatic impact on Italian art in the fourteenth century.

Gothic Art

As the political and cultural heir of the western Roman Empire, the Holy Roman Empire founded by Charlemagne consciously imitated the art and architecture of the period before the fall of Rome. In architecture particularly this imitation was often crude and barbaric, and was contemptuously dismissed by Renaissance writers as ‘Gothic’. Although the term is grossly inaccurate and misleading, it has been retained as a convenient name for the art and architecture from the end of the first millennium to the start of the Renaissance.Extravagant Architecture

The Gothic style arose primarily out of a desire by newly Christianized peoples to build churches, monasteries and cathedrals on a grand scale; consequently, the term 'Gothic is largely associated with extravagant vaulting, spires, flying buttresses and elaborate tracery. These edifices were distinguished by their huge, tall windows which encouraged the development of stained glass, but whose walls left relatively little scope for mural painting.The Art of Illumination

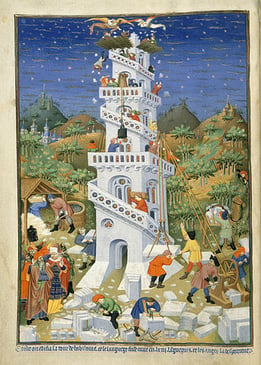

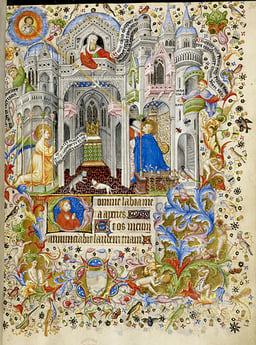

Fine art in this period made advances through the medium of illuminated manuscripts, but this was a skill practised in every monastery. Working on parchment, the limners outlined their pictures in various coloured inks and used tempera (a mixture of various pigments with egg-yolk, oil and water) and gold leaf to create everything from an ornamental initial letter to a complete illustration in the manuscript copies of the Gospels, psalters and breviaries. Before the invention of printing from movable type, the only books were those laboriously copied by hand, a labour of love for the greater glory of God.

Inevitably there was also a secular parallel development when kings, princes and great merchants commissioned prayer-books, known as ‘books of hours’, which differed from the monastic works in their greater use of scenes drawn from everyday life. These books were produced by artists who might have learned their craft in a monastery, but who operated in purely commercial workshops. It is significant that while we know little of the identity of the monastic limners and scribes, the earliest identifiable artists in western Europe were those like Jean Pucelle of Paris and the Limbourg Brothers of Flanders, the respective creators of the magnificent Belleville Breviary and the Très Riches Heures du Duc de Berry.

Painting in Miniature

The word miniature has passed into the English language as a synonym for something tiny, or a representation of something on a much-reduced scale. In fact the word is derived from the Latin minium, which had nothing to do with size at all, but was the word used to describe cinnabar or red lead, used in the decoration of the borders of medieval manuscripts and the initial letters around which were woven tiny pictorial elements. Later the word miniature came to apply to these decorations rather than the red lines and, in turn, to signify any painting executed on a very small scale. In the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries such works were often described as ‘paintings in little’ or ‘limnings’ and the artists who practised this craft were known as limners, a corruption of the French enluminer and Latin illuminare (the verbs ‘to paint’).The art of miniature painting has a long, if at times sketchy, history that stretches all the way back to the fragments of the Egyptian Book of the Dead and some scraps from Roman Imperial times – tantalizing glimpses of an accomplished art that perished because the materials used have themselves barely survived. Miniature painters worked in tempera and watercolours but it was their skilful use of gold leaf (and more rarely silver foil) to embellish their illustrations that gave them their distinctly sumptuous qualities. The illuminated manuscripts of medieval Europe represent an astonishing range of styles and techniques. The manuscripts of the Irish monks, for example, exhibit a highly idiosyncratic blend of Celtic and Norse art, totally different from the Anglo-Saxon art practised in the monasteries of England.

Fresco Painting

The fall of Constantinople brought a flood of refugees to western Europe with the accumulated learning, skills and technology of the East, but the Byzantine influence was making itself strongly felt long before this point.

Church Decoration

In the thirteenth century a change in Italian ecclesiastical architecture left more wall space, which demanded suitable decoration. We shall probably never know who was the genius who first stumbled upon the technique of painting on wet lime plaster, using colours ground and mixed with lime water. As the plaster dried the colours were fixed, just as if they had been applied to pottery then fired in a kiln. The problem with this technique was that the plaster set quickly, so fresco painting (as it was termed) had to be executed swiftly to a careful plan, because it was impossible to repaint once the plaster had dried. Although this style of painting was immensely popular all over Europe, by its very nature it was unsuited to the prevailing damp climate of northern Germany, the Low Countries or Britain, with the result that few medieval frescoes have survived intact. Even in Italy, many of the frescoes painted for churches have not stood the ravages of time and weather.

Assisi – a Cultural Centre

The greatest impetus to fresco painting came in the late thirteenth century, when the Franciscan order created the magnificent foundation at Assisi in honour of St Francis. The Franciscans recruited the best artists from all over Italy and thus Assisi briefly became an important centre where painters came together, argued and exchanged ideas. A large part of the decoration at Assisi was carried out by Bencivieni di Pepo, nicknamed Cimabue (‘ox-head’), in around 1280. Trained in the Byzantine tradition, Cimabue (c. 1240–c. 1302) transformed it and laid the foundations for a distinctive Italian style. Few frescoes by this Florentine painter have survived, but those that are still extant reveal his role in effecting the transition. The influence of Byzantine icon-painting is still very strong in his Maestà (1280), but the Madonna on her majestic throne has a much softer, more human expression than one would find in icons of the period.

The artist’s radical departure from the Byzantine tradition was continued by his pupil and successor Giotto di Bondone (1266–1337), who combined a more flexible approach to composition with portraiture, a style that conveyed both the feelings and character of the subject in a manner never previously attempted, far less achieved.

If you love the bright, sumptuous art of illuminated manuscripts, you’ll enjoy our book Illuminated Manuscripts Masterpieces of Art, as well as our beautiful perpetual diary A Book of Days, or our Marriage Feast at Cana journal.