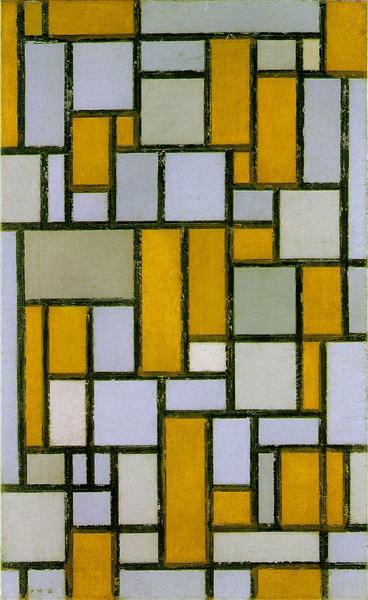

Neoplasticism was a twentieth century Dutch artistic movement consisting primarily of artists and architects. Founded in 1917 in Amsterdam, it advanced abstraction, simplifying paintings to the bare essentials of form and colour; for example only primary colours and black and white would be used alongside squares, rectangles or straight horizontal and vertical lines. Cubist painting and Neopositivism influenced the movement and Dutch artist Piet Mondrian (1872–1944) outlined the principles of Neoplasticism in his essay ‘Neo-Plasticism in Pictoral Art’. The movement would start to influence architecture, interior design, fashion and famously the German art school Staatliches Bauhaus, commonly known as Bauhaus.

De Stijl and Neoplasticism

De Stijl and Neoplasticism

Several artists in the first decades of the twentieth century, such as Robert and Sonia Delaunay (1885–1941, 1885–1979), Wassily Kandinsky (1886–1944) and Kazimir Malevich (1878–1935), had experimented with non-representational paintings. In France, Henri Matisse (1869–1954) had progressed from his Fauvist works to paintings like The Piano Lesson (1916), which asserted the flatness of the picture plane, eliminating depth and volume in favour of the abstract play of lines and colours. These developments, however, were to find their most extensive and coherent exploration in the work of Piet Mondrian, and of the group to which he belonged, De Stijl (‘the style’), active between 1917 and 1932.

Mondrian’s Early Years

Mondrian’s early work was inspired by Fauvist painting, showing brightly coloured and expressively painted landscape motifs, and between 1911 and 1914 he lived and worked in Paris, absorbing the new developments in Cubist art. A group of works based on single trees from this period show the artist’s paring down of his motif, reducing the leaves and branches to a series of schematic markings or signs on a flat surface, and creating an overall pattern that appears to be held in place by fragments of rectangular and squared-off lines. The abstract paintings that Mondrian produced in these years had their origins in landscapes or still-life, which were now totally integrated into a rhythmic grid of squares and rectangles composed in muted shades of grey, pale blue and ochre. In the most extreme works of 1914–17, the shapes of the sea and pier at Scheveningen, near The Hague, were indicated only through a succession of monochrome ‘plus’ and ‘minus’ shapes. In his writings, Mondrian felt that this point of departure in nature was hindering his art, as nature aroused feelings and emotions that got in the way of what he called ‘universal harmony’. He wanted to reduce the markings of his paintings even further, and create a new harmonious reality using elements of form and design.

Mondrian and De Stijl

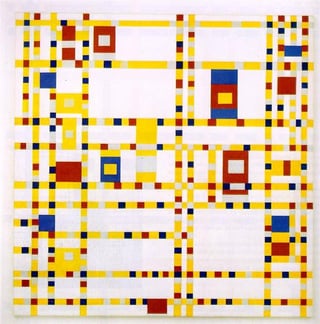

Around 1917, Mondrian met the painter Theo van Doesburg (1883–1931), who was the leading figure behind the founding of the De Stijl group and the editor of a journal of that name through which ideas could be propagated. For van Doesburg and for the designer Gerrit Rietveld (1888–1964), another member of the group famous for his Red-blue Armchair (1917–18), colour was crucial. Under their influence, Mondrian began to use colour as a fundamental part of his compositions in its most basic form: the three primary colours of red, yellow and blue; and the three non-colours black, white and grey. According to his own theory of what he termed ‘Neoplasticism’, published in De Stijl in 1919, Mondrian’s ultimate aim in painting was to reduce representation to its most elementary function: ‘In painting you must first try to see composition, colour and line and not the representation as representation. Then you will finally come to feel the subject matter a hindrance.’ Mondrian’s best-known works pursue this aim, consisting of a series of rectangles in primary colours separated by a grid of black vertical and horizontal lines. These separating lines were necessary so that a painted rectangle would not suggest any illusion of depth. Paintings such as Composition with Red, Yellow, Blue and Black (1921) were intended to be completely impersonal, controlled and harmonious, creating a sense of balance that for Mondrian had a strong spiritual meaning. Mondrian would maintain his austere artistic vision rigorously throughout the rest of his career, developing variations on the essential principles of his compositions, such as lozenge-shaped canvasses as the basis for his groupings of lines and colours.

The Influence of Theo Van Doesburg

Theo Van Doesburg’s work had made a crucial contribution to the development of De Stijl in his use of a strong asymmetricality, shown, for example, in his painting The Cow (1917), with its carefully placed flat blocks of colour – in this case pink, blue, yellow and black – on a plain white background. Van Doesburg also created a series of compositions based on diagonal forms, whose pattern of horizontal and vertical lines and rectangles were shifted through 90 degrees, to dynamic effect. Mondrian’s belief in contrasting pictorial elements was extended by Van Doesburg to a vision of all of the arts: painting, sculpture, music and architecture. Architecture and applied design, particularly interior décor, furniture and typography, were an important part of De Stijl’s overall programme. A style with clean, straight lines and no decoration was in part a reaction against the flowing qualities of Art Nouveau, and an assertion of the dominance of the man-made over the forms of nature. Van Doesburg’s interest in design and in the creation of functional objects also led him, in a manifesto of 1923 entitled ‘The End of Art’, to praise everyday items like bicycles, cars, irons and bathrooms, and to pronounce any attempt to renew art as it had previously existed as bankrupt: ‘Let us rather create a new life-form which is adequate to the functioning of modern life.’

Bauhaus

The Bauhaus (‘construction house’) art and design school has exerted an unparalleled influence on the visual culture of the last 90 years. It was founded in 1919 – in the chaotic aftermath of the revolutionary upheavals in Germany following its defeat in the First World War – with the intention of creating a place where all art could be brought together.

The characteristic ideology of the early Bauhaus was a Romantic anti-capitalism. It attracted as teachers artists such as Paul Klee (1879–1940), Wassily Kandinsky, Lyonel Feininger (1871–1956) and Johannes Itten (1888–1967), who at that time looked back to the imagined integrity of a pre-capitalist culture and forward to a new spiritual and social transformation. Klee and Kandinsky in particular brought with them the practices of Neoplasticism, influencing students towards abstraction with their own styles.

Bauhaus in Weimar

The first Bauhaus was located in Weimar, capital of the new republic but also symbol of the heights of eighteenth- and nineteenth-century German culture, of the Enlightenment and of Romanticism. Johann Wolfgang von Goethe (1749–1832), Ferdinand Schiller (1864–1937) and Franz Liszt (1811–86) had lived and worked there. From the beginning this new school and the unconventional, radical students it attracted were regarded with suspicion by local and regional government and by Weimar’s more respectable citizens. However, from late 1922 a change in school policy was evident. Walter Adolph Georg Gropius (1883–1969) had coined the slogan, ‘Art and Technology: a new Unity’. The old emphasis on the handicrafts seemed increasingly unsuited to the demands of modern industrial mass production. There were at least two factors involved in this change. The prolonged revolutionary crisis of 1918–23 seemed to be ebbing, and German capitalism was stabilizing and regenerating itself. Prospects for making links between the Bauhaus and industry looked promising. At the same time, cultural developments in the new Soviet Union seemed to show the way forward for a new unity of art, design and architecture, based on technology, not craft.

Wassily Kandinsky

Kandinsky taught at the Bauhaus in his later life, until it was closed down by the Nazis in 1933. He was born in Moscow and trained as a lawyer, but turned to art after visiting an exhibition of Claude Monet’s (1840–1926) work. He moved to Munich, where he studied under Franz von Stuck. Here, he demonstrated his talent for organizing groups of artists, when he founded the influential group Der Blaue Reiter (‘The Blue Rider’), which included Franz Marc (1880–1916), August Macke (1887–26) and Paul Klee – all Expressionist yet very distinct from each other in terms of technique.

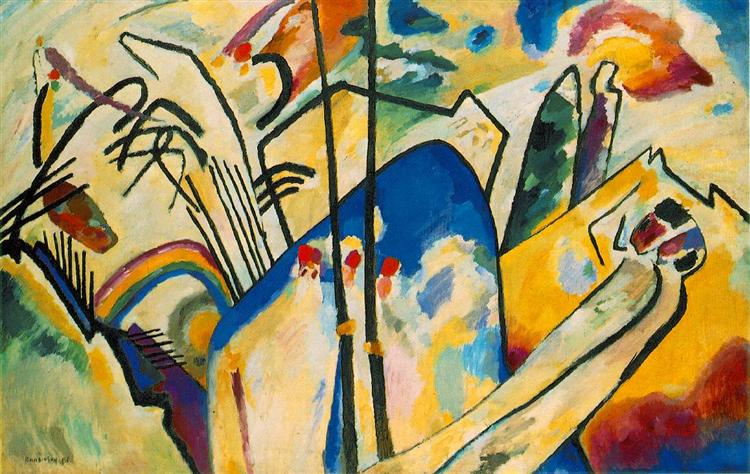

Kandinsky’s personal style went through many phases, ranging from Jugenstil (the German equivalent of Art Nouveau) to Fauvism and Expressionism. He is most celebrated, however, for his advances towards abstraction and Neoplasticism. This came about after he returned to his studio one evening, and was enchanted by a picture he did not recognize. It turned out to be one of his own paintings lying on its side. Kandinsky immediately realized that subject matter lessened the impact of his pictures, and he strove to remove this from future compositions.

Neoplasticism was an integral part of the journey of Modern Art. With its unique way of looking at painting and its methods of creating fascinating and emotive paintings from very simplistic colours and shapes, it is one of the more unusual artistic movements. If you’re interested in finding out more about the artists and works that shaped Neoplasticism, then be sure to have a read of our books, Wassily Kandinsky: Masterpieces of Art (ISBN 9781783612154) and Paul Klee: Masterpieces of Art (ISBN 9781783612086). If you’re already a fan of abstract works, perhaps this Mondrian foiled journal is for you.

Links

- For a more detailed look at Bauhaus, take a look at the Tate’s website here.

- Take a look at the Guggenheim’s website for more information on Piet Mondrian, and to see more of his works.

- For a fascinating biography of Wassily Kandinsky click here.