The clean, simple, pure forms of Neoclassicism arose as a counter movement to the frivolous Rococo style, particularly at a time when new discoveries from Pompeii were proving inspirational to artists. As a reaction against the Academies, however, the ideals of Romanticism – which favoured wilder, more emotional artworks – started to gain popularity. Offshoots of Romanticism began to appear throughout Europe, most notably in the work of the Nazarenes in Germany and the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood in England, who sought to take art back to a time before Raphael and his Classical influences had been a corrupting influence on art.

Neoclassicism

In 1755 archaeologists unearthed the ruins of Herculaneum and Pompeii, which had been engulfed by lava from Mount Etna in AD 79, and electrified the world by the beauty and naturalism of the mosaics and frescoes thus brought to light. Archaeology was then in its infancy, but the notion of lost civilizations that lay just below the surface of the modern world fired the popular and artistic imagination.

Johann Winckelmann (1717–68) studied theology then medicine before turning to art history, and it was while working as a librarian in Rome that he was inspired by the discoveries at Pompeii to embark on his great History of the Art of Antiquity (1764), which had a tremendous impact on the art world throughout the later years of the eighteenth century and right through the nineteenth century.

Classic and Simple

The first artist to exploit this resurgent interest in Classical subjects was J.M. Vien (1716–1809), whose painting La Marchande d’Amours excited favourable comment. He and his pupils, François-André Vincent (1746–1816) and Jean-Baptiste Regnault (1754–1829), took to heart Winckelmann’s famous dictum that beauty depended on calmness, simplicity and correct proportion, exemplified in Greek sculpture. These qualities were the direct opposite of Rococo and the reaction against its excesses resulted in the great movement known as Neoclassicism.

Its finest exponent was another pupil of Vien, Jacques-Louis David (1748–1825). Ironically, he gained little from studying under Vien but was inspired by the writings of Quatremère de Quincy, who seized on Winckelmann’s doctrine and expanded it for the benefit of his French audience. Greek painting of the Classical period had long since vanished but de Quincy urged French painters to study Greek statuary, and for this reason the earliest works by David and his contemporaries have a rather static appearance. Thus David’s great painting The Oath of the Horatii (1785) bears an uncanny resemblance to a Classical bas-relief in which form triumphs over colour. It was an immediate sensation, whose vigour and austerity were hailed as shining examples of all that was best in ‘republican virtues’.

‘Republican Virtues’

What was meant, of course, were the ideals of the Roman Republic, but the term would soon have an unfortunate resonance for France as the country was plunged into revolution. When the French Revolution erupted David shot to the top of the new artistic establishment, abolished the Academy and even designed a revolutionary uniform based on Classical lines. When Charlotte Corday stabbed Jean Paul Marat in his bath-tub, creating the first great martyr of the Revolution, David hastened to the gory scene to capture it in oils. His Death of Marat was painted in the best Classical tradition, with a patriotic feel that set the artistic standard for Roman republican ideals. Ironically, the man who dictated the doctrinaire precepts of the new republican art ultimately found himself in prison, as the Revolution took an uglier twist, but he survived the ordeal and was restored to favour under Napoleon Bonaparte.

In France, David strongly influenced Pierre Narcisse Guérin (1774–1833), a Neoclassicist who outdid even David in his sense of the melodramatic. Both Guérin and Antoine Jean Gros (1771–1835) became pillars of the French art establishment and received peerages in recognition of their achievement. Guérin then taught Théodore Géricault (1791–1824) and Eugène Delacroix (1798–1863), but like Guérin, they turned from Neoclassicism to Romanticism, unlike poor Baron Gros, whose attempts to keep Classicism alive led to his work being ignored – an unhappy situation that drove him to suicide.

Defending Classicism

Infinitely more successful in fighting for the Classicism cause was a strong supporter and student of David's, Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres (1780–1867). He succeeded because he strove towards a greater purity and in so doing created a style of expression that was all his own. But he was sometimes accused of being ‘Gothic’ or even ‘Chinese’, and he held a long artistic feud with Delacroix. Ironically, Ingres did what Gros failed to do, and eventually moved with the times, producing portraits – thoroughly modern in their realism – of the self-satisfied upper middle classes of the Second Empire when he was in his eighties.

The chief exponent of Neoclassicism in Germany itself was Anton Raffael Mengs (1728–79), who painted religious and historical subjects conveying the restrained emotions and heroic style of the neo-classical period (working as a painter to the royal courts of Saxony, Poland, Naples and Spain). Mengs lacked the passion and patriotic fervour of David, but in the last years of his life he worked in Madrid, where he created the great Apotheosis of the Emperor Trajan for the dome of the grand salon in the Escorial. Perhaps his greatest contribution to the development of European art was the fact that he taught Francisco Goya (1764–1828).

It should be noted that Goya, the spiritual heir of Velázquez, was very much his own man, using a great many sources for his work and developing his own highly individual style. As such, though he was introduced to a range of Neoclassical ideas and techniques by Mengs, this was quickly subsumed in the extremely versatile range of Goya’s output. The last of the great eighteenth-century painters, he was also the father of nineteenth-century art and the precursor of modern art.

Offshoots of Romanticism

As we saw in a previous Art Movements blog Romanticism | The Power of Imagination, the popularity of Neoclassicism began to wane in favour of a new style: Romanticism. Although France dominated the Romantic movement, as it had done Neoclassicism, it had its counterparts in other parts of Europe.

German Romanticism

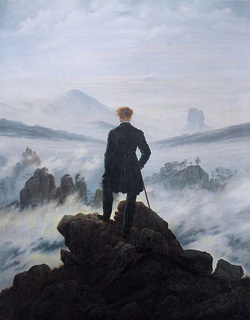

Friedrich – Painter of Wild Landscapes

The German artist Caspar David Friedrich (1774–1840) is usually regarded as belonging to the Romantic movement, although there was a fundamental difference between the French Romantics, who tended to regard nature as a substitute for God, and Friedrich, who saw painting as a medium for worshipping God. His preference was for the grandeur of lofty and rugged mountains and wild places, invariably painted by moonlight or at dawn or sunset in order to make the most of the special effects of the sun’s rays. He was something of a loner, supremely confident in his own talents without the need to seek out like-minded artists from whom he might learn, or to whom he could impart his ideas.

Friedrich studied drawing under J.G. Quistorp in Greifswald before going to the Copenhagen Academy between 1794 and 1798. On his return to Germany he settled in Dresden, where he spent the rest of his life. His drawings in pen and ink were admired by Goethe and won him a Weimar Art Society prize in 1805. His first major commission came two years later in the form of an altarpiece for Count Thun’s castle in Teschen, Silesia, entitled Crucifixion in Mountain Scenery. This set the tone of many later works, in which dramatic landscapes expressed moods, emotions and atmosphere. Appointed a professor of the Dresden Academy in 1824, he influenced many of the young German and Scandinavian artists of the mid nineteenth century and as a result he ranks high among the formative figures of the Romantic movement. For many years his works were neglected, but in the early 1900s they were rediscovered and revived.

The Nazarenes

To be sure, there was a group of German painters who sought a spiritual aspect to their work, but they were expatriates, working in Rome, where they formed a quasi-monastic order known as the Brotherhood of St Luke. This group was founded by Friedrich Overbeck (1789–1869) and Franz Pforr (1788–1812) as a reaction against the doctrinaire academicism of Vienna. After Pforr’s death the group was reformed as the Nazarenes, whose later members included Peter Cornelius (1783–1867) and Julius Schnorr von Carolsfeld (1794–1872). Their paintings of biblical subjects and historic scenes were distinguished by their bright colours and deliberately medieval appearance.

The Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood

The counterpart of the Nazarenes in Britain was the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood, founded in 1848 by Dante Gabriel Rossetti (1828–82), William Holman Hunt (1827–1910) and John Everett Millais (1829–96) as a reaction against the prevailing Neoclassicism of the Royal Academy. They consciously strove to return to the early Italian Renaissance, before the advent of Raphael (hence their name). Like the Nazarenes, they had a penchant for sharply incised outlines and brilliant colours.

Rossetti – Father of the Femme Fatale

Rossetti came from a hugely talented family. His father was a noted scholar while his sister Christina became a celebrated poet. For years Rossetti wavered between a career in art or literature, before devoting himself to painting. While still only 20, he helped to found the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood, the radical group that shook the Victorian art world with their controversial exhibits at the Royal Academy in 1848. The Pre-Raphaelites were appalled by the dominant influence of sterile, academic art, which they linked with the teachings of Raphael – then regarded as the greatest Western painter. In its place, they called for a return to the purity and simplicity of medieval and early Renaissance art.

Although championed by the art critic John Ruskin, the Pre-Raphaelites’ efforts were greeted with derision and this discouraged Rossetti from exhibiting again. During the 1850s, he concentrated largely on watercolours, but in the following decade he began producing sensuous oils of women. These were given exotic and mysterious titles, such as Monna Vanna and were effectively the precursors of the femmes fatales, which were so admired by the Symbolists.

The Pre-Raphaelite Legacy

Although the Pre-Raphaelites soon went their individual ways, they exercised a profound influence on the next generation of English painters, notably Edward Burne-Jones (1833–98) and Lawrence Alma-Tadema (1836–1912), while their principles were also endorsed by William Morris (1834–96).

Burne-Jones studied at Oxford where he met Morris and Rossetti, who persuaded him to give up his original intention of entering holy orders and concentrate on painting instead. He was also heavily influenced by Ruskin, who introduced him to the paintings of the Pre-Raphaelites and with whom he travelled to Italy in 1862. On his return to England he embarked on a series of canvasses that echoed the styles of Botticelli and Mantegna, adapted to his own brand of dreamy mysticism in subjects derived from Greek mythology, Arthurian legend and medieval romance. Burne-Jones, made a baronet in 1894, was closely associated with the Arts and Crafts movement, designing tapestries and stained glass for William Morris, as well as being a prolific book illustrator.

If you love the ethereal style of the Pre-Raphaelites, then you should take a further look at our book Pre-Raphaelite Masterpieces of Art, which showcases many of their artworks in full-page glory.

Links

- The Metroplitan Museum offers more insight into Neoclassicism here

- Caspar David Friedrich's artworks have been collected together on this website

- The Tate offers even more detail on the Pre-Rapahelite movement here