The Renaissance period occurred from the 14th to the 17th century, starting in Italy and spreading to the rest of Europe to mark the fall of the Middle Ages and the rise of the Modern world. New techniques and artistic sensibilities began to emerge alongside a new humanist philosophy, which demonstrated itself in all areas of thinking, including art, architecture, literature, music, politics, religion and science.

Early Renaissance Art

It is widely accepted that the Renaissance began in Florence, with the first truly Renaissance artists emerging in 1401. Young sculptors including Donatello (c. 1386–1466) and Lorenzo Ghiberti (1378–1455) as well as Filippo Brunelleschi (1377–1446), architect of the dome of Florence cathedral, created a number of well-known works.

Although France was at the nadir of its fortunes as a result of the Hundred Years’ War with England (which occupied Paris itself), Renaissance artists started to emerge there too. Among them was Jean Fouquet (c. 1420–c. 1480), who raised portraiture to a new level (painting on canvas instead of the more usual wood support), in full-scale works as well as in miniatures, and demonstrated how, even in vicissitude, a country can still produce great art.

The wealth of the merchant princes who controlled the affairs of the great Italian cities created a patronage of the arts that has not been exceeded since. This period coincided with the rise of the papacy, and an unparalleled era of church building in the Italian style, which yielded huge expanses of interior walls for decoration. This was the golden age of elaborate altarpieces and fresco painting, a technique in which paint would be applied to wet lime plaster that would fix the colours in place as it dried. Artists vied with each other in painting the Holy Family and biblical scenes, into which was breathed the fresh air of the new Renaissance humanism. Religious works were given a contemporary slant and made free use of ordinary everyday scenes. A new realism pervaded these paintings, enhanced by much greater attention to detail. Pisanello (1380–1456) and Masaccio (1401–28) pioneered the study of the human form and made the nude figure a respectable subject for ecclesiastical decoration – a notion taken to its logical conclusion by Masolino da Panicale (1385–1447) in his great Baptism of Christ.

Mastering Perspective

The development of perspective in the Renaissance era was part of the artistic trend towards realism. In the background architecture of Masaccio’s paintings we can see the striving towards a mastery of perspective; had he not died so young, who knows what he might have achieved. As it was, it was his colleague Paolo Uccello (1397–1475) who solved the problem. Indeed, Uccello became obsessed with creating a three-dimensional illusion that might emulate the great bronze bas-reliefs of Lorenzo Ghiberti (1378–1455), in whose workshop he had originally been employed as a mosaicist. Andrea del Castagno (1423–57) also experimented with perspective and the use of space and lighting. Piero della Francesca (c. 1420–62), though not a Florentine, subsequently came under the influence of Uccello and Masaccio and likewise sought the solution to the problems of perspective, eventually writing a couple of treatises on the subject.

High Renaissance Art

Painters who had begun their careers as stone carvers or sculptors included Sandro Botticelli (1444–1510), Antonio Pollaiuolo (c. 1429–98) and Andrea Verrocchio (1435–1488), and they too strove to achieve those attributes which would give their paintings a proper sense of distance. These artists came to the fore just at the time the Renaissance ideals of secularism and humanism were at their most pervasive, but were overshadowed by the next generation.

Leonardo da Vinci

Foremost, of course, was Leonardo da Vinci (1452–1519), whose life was synchronous with the High Renaissance and who was the most perfect example of the Renaissance man, excelling in an extraordinary diversity of disciplines, as an architect, sculptor, designer, military engineer and inventor as well as a painter. Not only did he produce one of the greatest masterpieces of all time, the Mona Lisa, but he was also one of the first Italian artists to employ landscape as an extension of the subject rather than merely to fill the background.

Leonardo was the illegitimate son of a notary and probably trained under Andrea del Verrocchio (c. 1435–88). In 1482 he moved to Milan, where he worked for the Sforzas. His chief work from this period was a majestic version of The Last Supper. The composition dazzled contemporaries, but Leonardo’s experimental frescoe technique failed and the picture deteriorated rapidly. This was symptomatic of Leonardo’s attitude to painting: the intellectual challenge of creation fascinated him, but the execution was a chore, and many of his artistic projects were left unfinished. Leonardo returned to Florence in 1500, where he produced some of his most famous pictures. These were particularly remarkable for their sfumato – a blending of tones so exquisite that the forms seem to have no lines or borders. He spent a second period in Milan, before ending his days in France. Leonardo’s genius lay in the breadth of his interests and his infinite curiosity. In addition to his art, his notebooks display a fascination for aeronautics, engineering, mathematics and the natural world.

Michelangelo

Michelangelo (1475–1564) had many of Leonardo’s attributes, as well as being a poet of considerable ability. Though best known as a sculptor, in later life he produced paintings of such sublime power as to place him in the first rank. He was raised in Florence, where he trained briefly under Domenico Ghirlandaio (1449–94). Soon Michelangelo’s obvious talent brought him to the notice of important patrons. By 1490, he was producing sculpture for Lorenzo de Medici (1449–92) and, a few years later, he began his long association with the papacy.

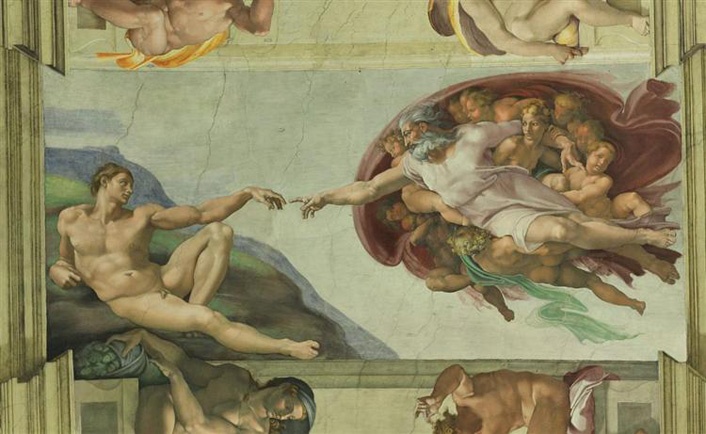

Michelangelo’s fame proved a double-edged sword. He was often inveigled into accepting huge commissions, which either lasted years or went unfinished. The most notorious of these projects was the Tomb of Julius II, which occupied the artist for over 40 years. Michelangelo always considered himself primarily a sculptor, and he was extremely reluctant to take on the decoration of the Sistine Chapel. Fortunately, he was persuaded, and the resulting frescoes are among the greatest creations in Western art. The ceiling alone took four years (1508–12), while the Last Judgment (1536–41) was added later on the altar wall. In these, Michelangelo displayed the sculptural forms and the terribilità (‘awesome power’), which made him the most revered artist of his time.

Raphael

Michelangelo’s near contemporary was Raphael (1483–1520), who trained in the Umbrian School but later acquired the positive qualities of the Florentine School. He had the good sense to graft on the best precepts from Leonardo and Michelangelo. The end result was a noble style that transcended the sum of its parts and was universally regarded as the quintessence of a pure and perfect harmony. The religious paintings of Raphael are so well known that it is difficult to realize how startlingly novel they struck his contemporaries. He breathed new life into the hackneyed subject of the Madonna and Child and other aspects of the Holy Family, which were an obligatory part of the repertory of every artist of the period.

Raphael received his education in Perugino. In 1504, he moved to Florence, where he received many commissions for portraits and pictures of the Virgin and Child. Soon, his reputation reached the ears of Pope Julius II, who summoned him to Rome in 1508. Deeply influenced by Michelangelo he added a new sense of grandeur to his compositions and greater solidity to his figures. Michelangelo grew jealous of his young rival, accusing him of stealing his ideas, but Raphael’s charming manner won him powerful friends and numerous commissions. The most prestigious of these jobs was the decoration of the Stanze, the papal apartments in the Vatican. This was a huge task, which occupied the artist for the remainder of his life. The School of Athens is the most famous of these frescoes. Other commissions included a majestic series of cartoons for a set of tapestries, which were destined for the Sistine Chapel, and a cycle of frescoes for the banker, Agostino Chigi.

In the midst of this frantic activity, however, the artist caught a fever and died, at the tragically young age of 37. Despite this Raphael, more than any other artist of the High Renaissance, is due the credit for establishing Rome as the artistic centre of the Western world – a position that remained unchallenged for more than 200 years.

Depicting light and perspective with greater realism and effect than had ever been conceived before, the Renaissance artists brought us in to the modern world. If you’re interested in finding out more about this incredible era, then be sure to take a look at our book Michelangelo: Masterpieces of Art (ISBN 9781783613618) and our Da Vinci Vitruvian Man luxury foiled journal.

Links

- For a broader look at the Renaissance period itself take a look here.

- The Tate offers a fantastic introduction to Renaissance era art.

- Learn more about Leonardo da Vinci’s Mona Lisa.