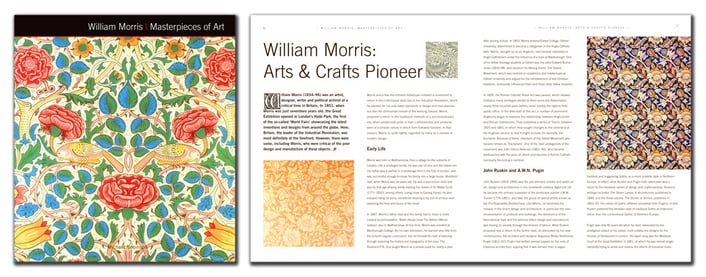

-crops.jpg?width=150&height=220&name=ransom_wallpaper_(fruit)-crops.jpg) On Thursday, a new exhibition on visionary artist, craftsman and activist William Morris opens at the National Portrait Gallery. It is exciting for its angle – rather than focus purely on the work for which he is probably best known (his understandably popular and beautiful wallpaper and textile designs), it will take a thoughtful look at his life, ideas and legacy, 'through portraits, personal items and fascinating objects'. It will explore his passionate belief in the democracy and availability of beauty – an 'art for the people' – alongside the work of his contemporaries (Rossetti, Burne-Jones) and those he inspired for decades to come (from courageously openly gay philosopher Edward Carpenter, and sculptor and typeface designer Eric Gill, to the artists of the 1951 Festival of Britain and post-war designers such as Terence Conran).

On Thursday, a new exhibition on visionary artist, craftsman and activist William Morris opens at the National Portrait Gallery. It is exciting for its angle – rather than focus purely on the work for which he is probably best known (his understandably popular and beautiful wallpaper and textile designs), it will take a thoughtful look at his life, ideas and legacy, 'through portraits, personal items and fascinating objects'. It will explore his passionate belief in the democracy and availability of beauty – an 'art for the people' – alongside the work of his contemporaries (Rossetti, Burne-Jones) and those he inspired for decades to come (from courageously openly gay philosopher Edward Carpenter, and sculptor and typeface designer Eric Gill, to the artists of the 1951 Festival of Britain and post-war designers such as Terence Conran).

But how much do you know of William Morris? Here's a bit of background on the man and artist for those of you unfamiliar with this giant.

Early Life

Morris was born in Walthamstow, then a village on the outskirts of London, into a privileged family. He was one of nine and the eldest son. His father was a partner in a brokerage firm in the City of London, who was successful enough to move his family into a large house, Woodford Hall, when Morris was six years old. He was a precocious child and was by that age already avidly reading the novels of Sir Walter Scott (1771–1832) among others. In 1847, Morris’s father died and the family had to move to more modest accommodation, Water House (now The William Morris Gallery) also in Walthamstow.

While at Oxford University, Morris demonstrated a great deal of physical energy, enjoying both rowing and fencing. He was also an eminent debater, full of passion and at times quite vociferous in his opinions, which delighted his close-knit circle of friends that included Burne-Jones. It was around this time he was to abandon his plans to enter the clergy, and instead, along with Burne-Jones and the 'Birmingham Set', he found inspiration in naturalism in art advocated by Ruskin and the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood, and committed to arresting what he and others saw as a declining aesthetic.

At the beginning of 1856 Morris began an apprenticeship at the Oxford-based architectural practice of George Edmund Street (1824–81), an enthusiast of the burgeoning Gothic Revival style. It was during this time that he met Street’s assistant architect Philip Webb (1831–1915). In the summer of 1856, Street moved his practice to London. Morris went with him until the autumn of that year, moving into lodgings with Burne-Jones in Bloomsbury.

Rossetti and Painting

At this time the most charismatic of the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood, Dante Gabriel Rossetti, persuaded Morris to take up painting and put architecture aside. But Morris's foray into painting was short-lived when he realized he was unable to accurately depict figures, an aspect that was to hinder some of his later design work. Morris moved from his lodgings into Red Lion Square, still in the Bloomsbury district, where he began experimenting in woodcarving and clay modelling.

Jane Burden and The Red House

After they spotted her on stage, aspiring actress Jane Burden became Rossetti and Morris's model and muse. Both were captivated by her, but Morris was the one to propose and the couple were married in April 1859 and moved to Red House in Bexleyheath, just outside of South East London, designed by Philip Webb. Many of the ceilings, as well as the hall, stairs and landing, were decorated by Morris in abstract geometric patterns. Burne-Jones was commissioned to design stained-glass windows and to paint murals of medieval scenes. Morris also designed and wove many of the textiles, such as tapestries and curtains and other soft furnishings. Webb too was kept busy designing furniture and fittings for the new house.

Morris, Marshall, Faulkner & Co.

Morris founded the firm Morris, Marshall, Faulkner & Co at Red Lion Square initially in order to provide furniture and furnishings for Red House. Its founders were Morris, Rossetti, Burne-Jones, Webb and another Pre-Raphaelite artist, Ford Madox Brown (1821–93), together with two of Morris’s Oxford chums, the mathematician Charles Faulkner (1833–92) and the engineer Peter Marshall (1830–1900). In 1861 the Firm produced its prospectus, clearly outlining its aim of providing quality decorative arts using ‘artists of repute’. The firm became renowned for their stained glass windows.

Morris founded the firm Morris, Marshall, Faulkner & Co at Red Lion Square initially in order to provide furniture and furnishings for Red House. Its founders were Morris, Rossetti, Burne-Jones, Webb and another Pre-Raphaelite artist, Ford Madox Brown (1821–93), together with two of Morris’s Oxford chums, the mathematician Charles Faulkner (1833–92) and the engineer Peter Marshall (1830–1900). In 1861 the Firm produced its prospectus, clearly outlining its aim of providing quality decorative arts using ‘artists of repute’. The firm became renowned for their stained glass windows.

It was in 1862 that Morris created the first of his wallpaper designs, ‘Trellis’, which incorporated a floral motif intertwined within a wooden frame. Webb drew the design for the birds, as Morris’s figurative work was not sufficiently good.

Writing

An avid reader in his youth, it seems natural that Morris would turn his creative talents to writing. Morris’s first work of note was a collection of poems published in 1858 under the title The Defence of Guenevere and Other Poems. His next work was an epic poem, The Life and Death of Jason. The following year, in 1868, Morris began writing a series of twenty-four stories called The Earthly Paradise.

Queen Square Premises

In 1864 Morris decided to leave his country home and take new premises in Queen Square, Bloomsbury, to provide a shop, workshops and living accommodation on the top floor, living here until 1872. Jane moved back to London with him and began to move within the social circles that included Rossetti, with whom she was later to have an affair (using the country house that he and Morris were to lease together in 1871, Kelmscott Manor, as the base for his liaison). Meanwhile, Morris was designing and publishing more wallpapers.

Morris & Co.

Morris decided to dissolve the old partnership and Morris & Company was founded in 1875, with himself solely in charge. With Thomas Wardle (1831–1909), a dye maker with his own factory, was to work with Morris tirelessly to find the right sorts of colours using natural plants and he began building on the earlier successes of his wallpaper range, using heavier stock and more intricate designs. He expanded their range of domestic furnishings to include embroidered wall hangings, woven furnishing fabrics, carpets, rugs and tiles, as well as a limited amount of tableware. Furniture design and production continued under the direction of Philip Webb.

Politics

Towards the end of the 1870s, Morris became less involved with the running of the Firm as he spent increasing time pursuing his interest in politics. He had become acutely aware that it was only a minority of the population that could afford the products and services of Morris & Co., while a grinding poverty existed, which he attributed to the inequality of classes. He had become disenchanted with Liberal party politics under William Gladstone. Also, in 1877, Morris formed the Society for the Protection of Ancient Buildings (SPAB). This organisation flourished and exists to this day, working to save old and historic buildings from decay, demolition and damage due to insensitive or inexpert restoration.

He was later (in 1883) to join the Democratic Federation, a socialist organisation based on some of the principles of Karl Marx (1818–83). The Federation was seeking reforms in working practices, such as reduced working hours, the abolition of child labour and compulsory education for all. More radically they were seeking the nationalization of the means of production, wresting control from the privileged classes.

Kelmscott House ann Merton Abbey

Horrington House, the Morris’s London home since 1872, was proving to be too small for the family’s needs and in 1878 they moved into a much larger house called The Retreat. The house, still in the western suburbs, was closer to central London and Morris immediately renamed it Kelmscott House after his country home. This time coincided with a new direction for Morris’s design work: the weaving of carpets and textiles.

The success of Morris’s experiments in carpets and fabrics led him to begin a series of tapestries, which he considered the highest and most noble aspect of weaving. The first of these was ‘Acanthus and Vine’, woven at Kelmscott House in 1879. To facilitate the expansion of his business, Morris began employing weavers and, in 1881 Morris transferred his operation to Merton Abbey in Surrey, a former printing works about nine miles south of central London.

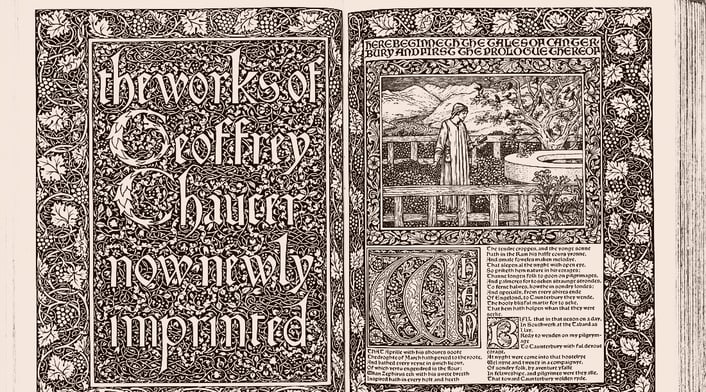

The Kelmscott Press

Morris loved medieval books and illuminated manuscripts, having seen these first hand in the Bodleian Library while studying at Oxford. Renting a cottage close to Kelmscott House, Morris established his own printing presses based on medieval examples to produce copies of his poems and tales, together with some medieval classics such as Chaucer’s Canterbury Tales. For Morris his book printing was a labour of love, his swan song. The books were expensive to produce and to buy, because they were intended to be savoured not just for the prose, but as objects of art in themselves.

Death and Legacy

Morris's health deteriorated after 1892, and in January 1896 he gave his last political speech. In June of that year, he and Burne-Jones were together to see the first two copies of the ‘Kelmscott Chaucer’ back from the binders. He died on the morning of 3 October.

During his lifetime Morris was best known by the public as a poet rather than a designer. Conversely, it is his legacy as a designer, rather than a writer, that continues to resonate today.

This text is based on extracts from our beautiful new book William Morris: Masterpieces of Art (ISBN 9781783612130).

Links

-

Apparently the sandal is the epitome of left-leaning, middle-class intellectuals such as Morris – this is the Guardian's take on the upcoming exhibition.

-

Visit the delightful William Morris Gallery in Walthamstow for the best introduction to the life and legacy of the Morris.

-

The V&A is also a fab place to go to see an extensive collection of wallpaper, textile and tile designs by Morris & Co.