Last Wednesday saw the return of the popular ‘Museum Selfie’ day, a Twitter project initiated last year by the group of Museum professionals behind the website CultureThemes. The hashtag ran rife, with people posing in front of famous paintings, re-sharing the altered Vermeer image, and making museum exhibits look desperate to take a picture of themselves. The craze of the selfie in recent years – ‘selfie’ was named Oxford Dictionary’s 2013 Word of the Year – highlights what could be described as an addiction to self-portraiture, and the enthusiasm for the ‘museum selfie’ in particular indicates a fundamental need or desire to acknowledge that self: for the photographer to become a part of the photo and exist within its created art. With the upcoming release of Flame Tree’s ‘Edvard Munch: Masterpieces of Art’, we thought we’d have a look at how Munch’s tormented and emotionally vibrant paintings depict the self, and how his emotions and experiences flavour as well as constitute the subject matter of his work

Last Wednesday saw the return of the popular ‘Museum Selfie’ day, a Twitter project initiated last year by the group of Museum professionals behind the website CultureThemes. The hashtag ran rife, with people posing in front of famous paintings, re-sharing the altered Vermeer image, and making museum exhibits look desperate to take a picture of themselves. The craze of the selfie in recent years – ‘selfie’ was named Oxford Dictionary’s 2013 Word of the Year – highlights what could be described as an addiction to self-portraiture, and the enthusiasm for the ‘museum selfie’ in particular indicates a fundamental need or desire to acknowledge that self: for the photographer to become a part of the photo and exist within its created art. With the upcoming release of Flame Tree’s ‘Edvard Munch: Masterpieces of Art’, we thought we’d have a look at how Munch’s tormented and emotionally vibrant paintings depict the self, and how his emotions and experiences flavour as well as constitute the subject matter of his work

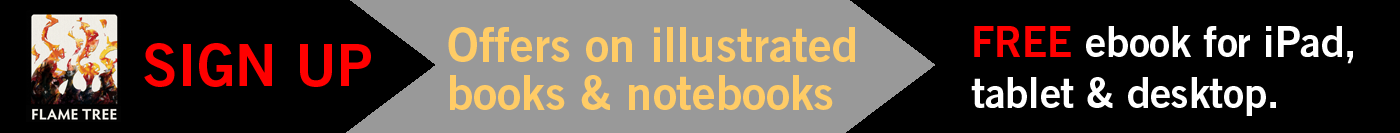

Self-portraits have long been a custom in paintings, and the work of Edvard Munch was no exception. Towards the end of his life he produced some especially gloomy self-portraits, though even in his earlier depictions of figures – for example, the androgynous character in The Scream – he expressed a version of the self. He documented his life through his paintings, attempting to convey the personal through art and inhabit his work with emotion, interiority and life. It is as though the inner self comes out of the subject of his paintings to seep into the background and very essence of the visible image.

Munch’s neuroses, which plagued him for most of his life, inspired much of his art, leading him to maintain that ‘without fear and illness, my life would have been a boat without a rudder’. He believed that he inherited ‘the seeds of madness’ from his father, and the early deaths of Munch’s mother and close sister Sophie affected him deeply. He began studies in engineering, though was frequently ill – he had been a sickly child too and kept a weak constitution throughout his life. Always, his work was a personal expression, giving form to an inner vision and attempting to probe and expose what lay beneath and behind the surface – what he called ‘soul art’. Munch considered perceptions of a place or person to be coloured by memory, contemplation and emotion, and chose to show this rather than an exact depiction – his wavering sense of self, as such, coloured any representation of himself. He captured moments, the feelings and pulsations of life. In effect, he attempted to paint the subjects of his paintings in all their subjectiveness: ‘people who live, breathe, feel, suffer and love’. In order for his work to authentically convey life, and age, Munch famously left his paintings out in the rain, and abhorred the varnish that was put on paintings to finish them, as he felt this coating did not allow his paintings to breathe.

Known to create multiple versions of the same picture, Munch obsessively reworked his paintings.For example, he produced at least twenty different versions of The Sick Child, including different colour combinations, and he considered this painting to be a breakthrough in his art. He would even go back, years later, and recreate new versions of his earlier works, painstakingly reconfiguring his images and bringing the lines, colours and shapes back to life. Munch’s best-known work, The Scream, formed part of a series entitled The Frieze of Life – a Poem about Life, Love and Death. A partner piece, Anxiety, has a very similar composition, and like The Scream captures an intense psychological expression, with the whole image, not just the figures, embodying those ‘oscillations of life’. Munch used colour and shape to convey emotion, and he intended his paintings to move viewers to their own personal reaction, believing the effect of the colours on people's emotions allowed him to create ‘an art that arrests and engages’.

Curiously, Munch had an idea of transforming the entire ‘Frieze of Life’ series into a graphic series called ‘The Mirror’. He started on the project, exhibited parts of it, and toyed with the idea for decades, but it never came to fruition. The suggested name ‘The Mirror’, however, still indicates the personal experience Munch expected his work to produce – he intended that anyone looking at those paintings would have seen themselves, as in a mirror.

Curiously, Munch had an idea of transforming the entire ‘Frieze of Life’ series into a graphic series called ‘The Mirror’. He started on the project, exhibited parts of it, and toyed with the idea for decades, but it never came to fruition. The suggested name ‘The Mirror’, however, still indicates the personal experience Munch expected his work to produce – he intended that anyone looking at those paintings would have seen themselves, as in a mirror.

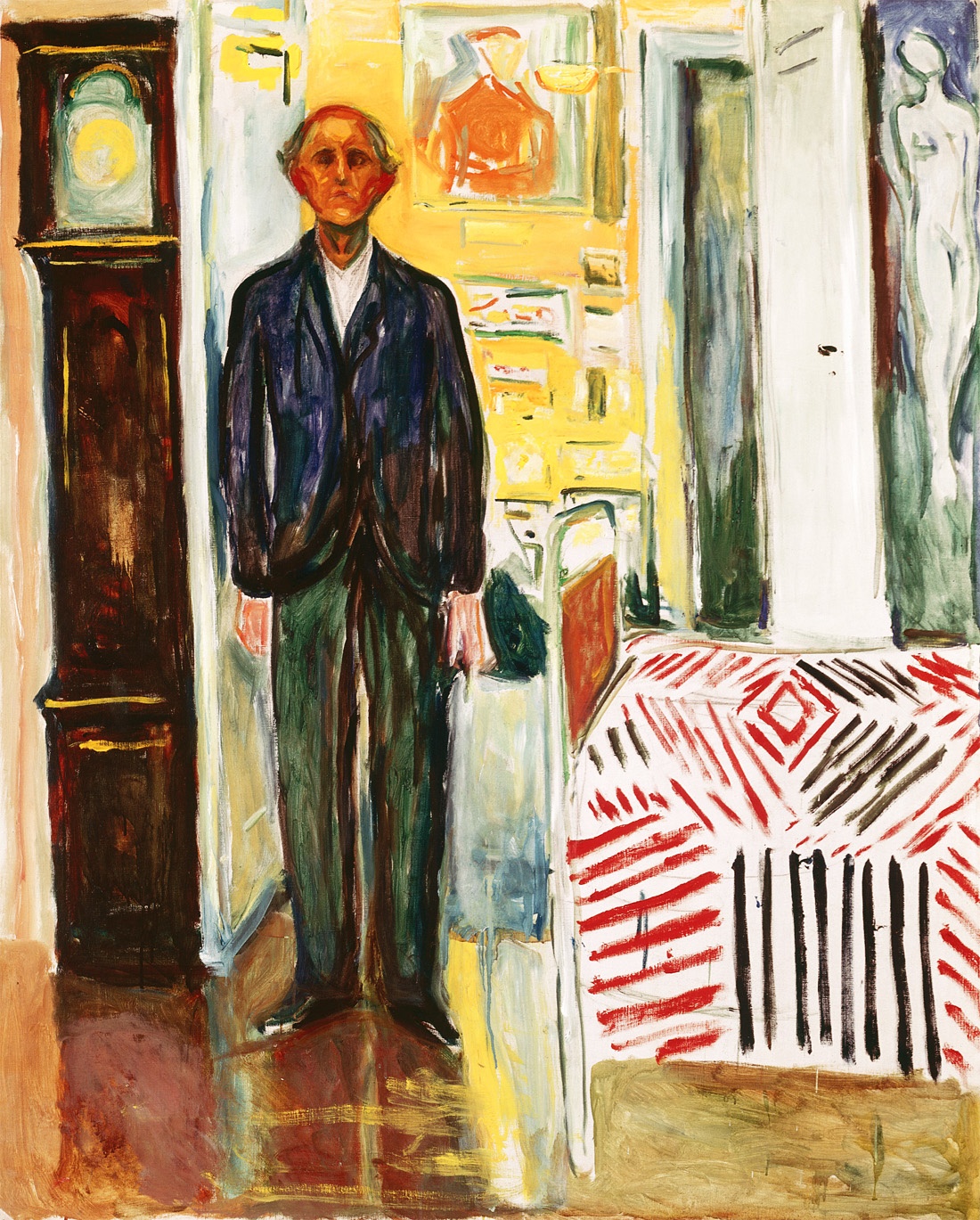

Munch’s later life was fraught with depression and breakdown, and he stayed in a number of clinics. A late self-portrait – Self-portrait between the clock and the bed (1940-43) – delivers the same impression of oscillation and intensity of colour as his earlier paintings, despite the seemingly passive expression on the figure’s face. The bed beckons like a final resting place, as the artist stands surrounded by his paintings and a grandfather clock marking the inexorable march of minutes and hours. Throughout his life, Munch wished to produce living, breathing paintings, and his expression of the self’s internal conflicts has made him a prominent figure in the art world.

You can read more about Munch in our upcoming title Edvard Munch: Masterpieces of Art, which you can preorder here [ISBN: 978-1-78361-356-4]. And if you’re a fan of Munch’s most famous painting The Scream, you might like to have a go recording your own interior thoughts in our Edvard Munch foiled journal, which is available now.

Links

-

Munch has been named as an influence by a number of Modern Artists, including Jasper Johns. Read about Jasper Johns here.

-

Danish art director Olivia Muus, who works at an advertising agency, has created the entertaining tumbler account Museum of Selfies.

-

See the top pictures from this year's Museum Selfie Day, via the Guardian.