Claude Monet (1840–1926) transformed French painting in the late nineteenth century. The term 'Impressionism' was taken from his painting Impression Sunrise (1872), which was exhibited in 1874, in the first of Monet's independent exhibitions that would give rise to the Impressionism movement. Throughout his long and successful career Monet became a master of colour and light; exploring the countryside, painting en plein air and capturing landscapes of Paris and Normandy and the beautiful water lilies and flowers in his own garden at Giverny.

Personal Life

Society

Monet was born at a time of tremendous change in France: industry was beginning to take hold, towns were being enlarged, transport networks were expanding, roads being improved and the development of railways opening up the interior. It was a time of growth, of the rapid expansion of the middle classes and also of political upheaval. Increasing wealth resulted in massive consumerism and a capitalist society that was nevertheless anxious about the acquisition of wealth and status.

The collection of art and the practice of art classes formed an important part of this bourgeois society and the background to Monet’s development. His family formed the very fabric of progressive French society and, despite Monet’s anti-establishment art, wealth and status remained crucially important to this complex artist.

The Formation of an Artist

His youth, one in which he exhibited a prodigious talent for drawing as well as a wicked sense of humour and a subversive nature, was spent under the auspices of the Second Empire and Napoleon III (1808–73).

He left school before taking his exams and shunned the traditional art academies in Paris, to his father’s chagrin, choosing his own path instead. Once chosen, he strode purposefully down this path to the end of his life, never deviating from his artistic aims.

Monet’s early friendship with the marine artist Eugène Boudin (1824–98) in effect shaped his career. It was Boudin who first took Monet to paint en plein air. The artist subsequently adopted the practice with vigour.

Throughout his life, with the exception of his still-life paintings, Monet continued to paint outdoors. His characteristic technique was to begin his paintings in this manner nearly always finishing them in the studio, creating a contradiction between the concept of painting the fleeting moment as it appeared and finishing it laboriously under studio conditions.

Friendships with other Artists

An important and often overlooked aspect to Monet’s development was his close friendships with other artists. Monet met Pierre Auguste Renoir (1841–1919), Camille Pissarro (1830–1903), Alfred Sisley (1839–99) and Frédéric Bazille (1841–70) in his early days in Paris; all of them young, avant-garde artists. These artists supported each other, painted alongside each other, exchanged ideas and techniques and formed long-lasting friendships. These bonds and shared experiences – the monthly dinners in Paris in later years and meetings in such places as Café Guerbois, a Mecca for radical artists and writers of the day – were fundamental in shaping all of their careers.

Evidence from Monet’s numerous surviving letters indicate he was a man of many friends from such diverse quarters as the radicals and critics Octave Mirabeau (1848–1917) and Gustave Geffroy (1855–1926), to the writer Emile Zola (1840–1902), the poet Stéphene Mallarmé (1842–98) and the politician Georges Clemenceau (1841–1929). He was a close friend of James Abbott McNeill Whistler (1834–1903) and in later years of John Singer Sargent (1856–1925).

By the end of his life, the little village of Giverny where he lived had attracted large numbers of young American artists, and it would be in America that his work would have particular influence on the development of modern art, seen through the work of the Abstract Expressionists.

Style & Techniques

Monet and his contemporaries shook the academic art world to its foundations during the latter part of the nineteenth century. They opened the door for progressive, modern art. Although Monet’s impact had waned in France by the time of his death, he was rightly established as a leading artist, if not the landscape artist of the twentieth century.

Depiction of Truth vs. Emotion

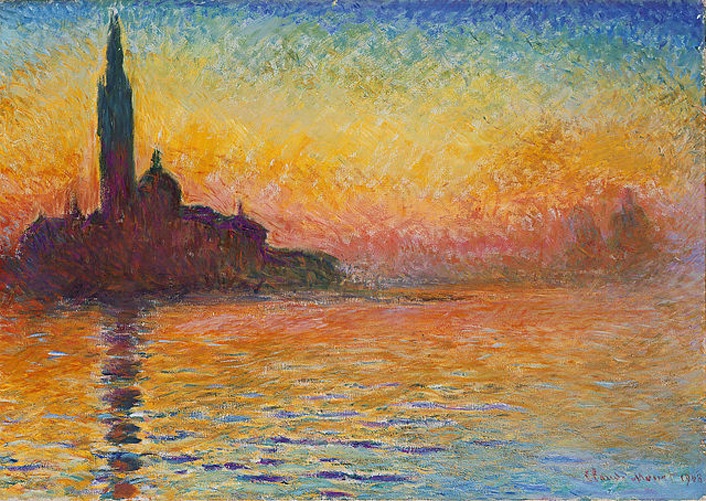

Monet’s absorption with the depiction of light and its effect on colour is clear in his early landscapes. It was a single unifying objective that ran throughout his work. He sought to create a visible record of truth, the fleeting moment of nature, but it was his own interpretation of truth and reality. As such, his paintings were a mechanical observation of the outside world, not necessarily a literal representation, but his own rationalisation of what he saw. This was a rationalisation without sentiment, which is one of the most defining aspects of Monet’s work.

With rare exceptions, such as Jean Monet on his Hobby Horse (1872), a painting of his son that was never exhibited during his life, Monet’s paintings were without attachment or emotion. Considering the artist painted only what was dear to him – his family, friends and nature – his cool detachment and rational approach to colour, light and atmosphere is all the more pronounced. Instead, figures, such as his wife or stepdaughters, are used as surfaces against which to evoke an impression of colour and light. This is seen to even greater extent in his series paintings, particularly those of Rouen Cathedral (1892–94) and his last water lilies (1903–26).

His desire to capture the object in an instant of light and atmosphere brought him closer and closer to that object, finally leading to its structural disintegration as colour and effect took over. Even his painting of his first wife Camille on her Deathbed (1879) is coolly detached and was, by his own account, a study of the colours of her gradual decline.

Yet family was of central importance to Monet, providing a refuge from early public rejection and a haven for the artist in later life. Despite the lack of sentiment in his paintings, his abundant letters reveal a man who deeply loved his family. These same letters reveal a man plagued by self-doubt.

Art from Monet's Own World

His paintings were always creations of his own world, a world that was safe and often removed from reality: the grime of industrial growth in towns such Argenteuil appears as faint puffs of smoke on a horizon; the smog of London becomes an ethereal, coloured atmosphere.

References to the atrocities of war, the deaths of his friends, both wives, his son and stepdaughter are absent in any obvious form from his work, emphasizing the detachment in his paintings. The sincerity and single mindedness of his objectives are tremendous.

The most extraordinary in these terms are his final works, his giant series of water lily paintings that are deeply introspective and reflective on both visual and cerebral levels. There is no horizon in these works: sky becomes water and water sky in an endless inversion of truth and reality. Painted at the end of his life following various bereavements and with an increasing sense of mortality, these great monuments of twentieth-century art are infinitely contemplative.

An Overall Harmony

An outstanding aspect of Monet’s work is its sheer beauty. He painted lovely things, and in the first stages of his career often painted the wealthy, fashionable middle classes at leisure. These paintings of boating and promenading should have appealed to the very people they depicted, but it was the manner in which he painted that initially offended both academic art circles and the public.

Monet treated all aspects of his scenes the same way, with the same freely expressed, textured brushwork, making no differentiation between a human figure and a field of poppies. While he might have chosen to paint the middle classes and the beautiful countryside, he did so to express a moment in time: a flash of sunlight on water, the dapple of light falling across a white dress or the colours of reflection in deep water.

His human figures were no more important in a landscape than a bank of trees, and in time they became barely discernible from the tall grasses of a meadow or monumentally dwarfed by the cliffs of a shoreline. For Monet, truth was not achieved through detail but in the overall harmony of nature.

After Death

Some months after the death of Claude Monet in December 1926, the Musée de l’Orangerie, Paris opened its doors to the public exhibiting Monet’s final grand statement – his Grandes Décorations. These huge water lily paintings were the culmination of 70 years’ work, painted by an artist who had achieved considerable wealth, fame and critical acclaim, and yet by the time the public saw them Monet’s star had begun to fade in Paris.

The radicalism of his work was being overshadowed by new movements – the Cubists, the Expressionists, the Fauves and others. He was no longer a leading, revolutionary figure and his final, great monuments were largely misunderstood. The politician and ex-Prime Minister Georges Clemenceau (1841–1929) wrote in 1928 that there were hardly any people in the Orangerie viewing the paintings, and most of those were young lovers seeking a secluded spot.

The genius of Monet was not rediscovered for some years, when his canvases were dusted down and his contribution to modern art truly understood. His work remained particularly popular in America and Europe, and within several decades of his death his genius was globally appreciated and his poetic vision recognised.

Intrigued and want to learn more about Monet? Or impressed and want to see more artwork? Both? Check out our beautiful illustrated book Claude Monet: Waterlilies & The Garden of Giverny. Or alternatively, give the gift of Claude Monet Masterpieces of Art to yourself or a friend for an insightful overview of Monet's life and works.

Links

-

Claude Monet was a key founding member of the Impressionist circle. To learn more about Impressionism, visit our blog post by clicking here.

-

To learn more about Monet's relationship with plants and nature, click here.

-

To book a visit to Monet's home and garden in Giverny where he lived and painted from 1883 to his death in 1926, click here.

-

Explore Monet's incredible painting techniques here.