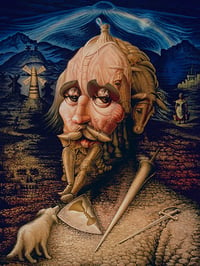

The Mexican painter Octavio Ocampo produces compelling, masterfully composed images that are testament to the idea that a picture’s meaning is constituted at least in part by the observer. Ocampo, who pursued a film and theatre career for some time alongside his art studies, uses the term ‘metamorphic’ to describe his art, which is also often described as surrealist. His evocative optical experiments are impressive, fascinating and somewhat disorientating. As he says: ‘Nothing is quite as it seems’. You look closer at his paintings and suddenly notice the plural realities within them, adding a sort of double-vision to the experience. Today we’ll explore some of Ocampo’s art, touching on the concerns that his paintings share with the works of the surrealist painter Salvador Dalí, the philosopher Ludvig Wittgenstein and the latin poet Ovid.

It is worth briefly unpacking the term ‘metamorphosis’ to understand its application to images and perception, and its use by Ocampo to describe his work. Metamorphosis expresses a physical or figurative transformation of some kind. The idea has a long literary history, including Ovid’s massively influential Metamorphoses and Kafka’s celebrated novella The Metamorphosis, which begins with the protagonist waking up one day to find himself transformed into a large insect: the story details the adjustment and transformation of his daily life and relationships as a result. Ovid’s work is comprised of fifteen books, and is effectively a collection of myths focussing on a ‘theme’ of metamorphoses, or changes, physical or otherwise. Metamorphoses progresses through a history of the world, beginning with the shift from chaos to creation in the universe. That it covers a ‘history’ brings to attention the element of time, which when coupled with the transformations enables those alterations instead to be regarded as a developments rather than a stationary changes. A change (in perspective, too) is as such movement forward, an addition to what has come before in the same way that Ocampo’s paintings let you first see one thing, then another, a double-take which broadens and develops your understanding of what you see rather than simply replacing the first impression.

Ovid’s great work is a masterpiece of stories within stories, just as Ocampo’s work embeds images and ideas within eachother. Ovid’s regular incorporation of Greek mythology, with its pantheon of deities embodying ideas such as Love or War, encourages his transformation of the figurative into physical symbols. It is a playful work that inverts the traditional portrayal – or image – of gods as important and human passions as trivial. As Metamorphoses also details a continuous process through time, death can be seen to transform into the life of something else: life and observation of that life is ever-changing. Ovid used this shape-shifting nature as a literary device, a way to play and create engaging narratives and events. In Ocampo’s work, it is similarly this versatile quality that is so captivating. His superimposed images allow for a protean interpretation: the observer finds themselves balancing two mutually exclusive ideas, vacillating between the realistic and figurative impressions. Seeing a previously hidden layer of meaning implies that there is more, and this forward progress and development in perception means that observing Ocampo’s paintings is far from being a static experience for the viewer.

Duck or Rabbit?

The well-known duck-rabbit image is an apt example of this form of illusion, where the brain experiences a second ‘recognition’ of an image as being something else. Wittgenstein, in his Philosophical Investigations (1953), uses this image in order to show the difficulty, or even impossibility, of ‘seeing’ both images at the same time. For Wittgenstein, observation and interpretation are inextricably linked – perception is itself an act of applying meaning and understanding. We see a picture, and automatically we see it ‘as’ something, our brain organising the observation by calling on memories of previous experiences and knowledge; we interpret the context through our particular lens. The massive role that our brain plays in creating what it sees or understands goes some way to explaining how the illusion of that infamous blue/black or white/gold dress worked so effectively. Wittgenstein used his work on Aspect Perception – seeing one thing in multiple ways – to posit that there is no fixed meaning for any word, arguing for the value in liberating the mind out of one-way interpretation. He describes the experience of realising another level of perception:

‘I contemplate a face, and then suddenly notice its likeness to another. I see that it has not changed; and yet I see it differently.’

While that the realisation and expression of a new perception feels like a change in the object, it is our awareness that has expanded, building on our memory of the first impression. Ocampo describes a similar process for the intended effect of his paintings:

‘I like to invite the observer to interact playfully with my paintings. First I capture his attention, and try to communicate a sense of beauty or of something terrible. Then, on the second or third impression, the observer should be feeling something quite different.’

Ocampo’s paintings create a curious sense that the eye has been tricked: as with most optical illusions the brain swings between the possible images with eternal ambivalence. Ocampo began his artwork by creating murals for churches and schools.

He joined a school of art while also dabbling in acting, stage-painting and film-making – he has made set designs for more than 120 American and Mexican films. Ocampo’s experience in the film industry may have helped to fuel his interest in optical tricks. Films predominantly seek to give the illusion of reality, and Ocampo would have been able to play with a scene, play with the reality it represented, and as such actively puppeteer an audience’s experience of what they see. Individual scenes and elements within those scenes constitute the impression of a whole film, as with his surrealist optical illusions. It is perhaps no coincidence that Salvador Dalí, too, was interested in film production. Dalí’s two films with Luis Bruñuel, L’Age D’Or (1930) and Un Chien Andalou (1929), brought his dreamlike ideas onto the screen. The films contain famously disturbing moments, such as an eyeball-slicing scene, and ants appearing crawling out of a human hand. The translation of Dalí’s ideas to film in this way made the images he created seem more ‘real’, as you could actually ‘see’ these things happening, or were made to think you saw them happening. Dalí’s own painting Metamorphosis of Narcissus (1937) is itself an optical illusion. Dealing with the myth of Narcissus (which, appropriately, also features in Ovid’s Metamorphoses), Dalí captures the part of the story were Narcissus is transformed by the gods into a flower: the double-image shows us the kneeling Narcissus, using the same shape for the hand holding the egg and flower.

Octavio Ocampo has also used the story of Narcissus in his work, and his paintings regularly feature famous figures as their ‘subject’: some examples include Mozart, Gene Kelly, Jimmy Carter, James Dean, Jane Fonda, John Lennon, Marlene Dietrich, Marilyn Monroe, Verdi, Cher and Don Quixote… as well as religious deities such as Krishna, Shiva, Buddha, and Christ, whose face is comprised – defined – by a prominent full body image of his crucifixion. Using recognisable figures in this way, the observer is already going into the image with a knowledge of the subject’s context. This would appear in keeping with Wittgenstein’s theory that such knowledge is fundamental to regard something ‘as’: to experience feelings of recognition and as such fully appreciate the multi-faceted representation of the person and scene. Ocampo’s images often involve a close-up of a face, with the face itself being made up individual, complete elements, such as flowers or landscape or scenes from that person’s life. The symbolic implications of such figures being actively defined by representations of their life or characteristics affords the interesting additional dimensions to his work.

Ocampo has also provided his take on paintings like Da Vinci’s Mona Lisa and Michelangelo’s Creation of Adam. His reimagining of the latter painting involves separate depictions of both the hand of God and the hand of Adam – Adam’s hand is comprised of a mini full Adam reclined and lazy, feet-first, lifted and pushed ahead by angelic putti. God’s hand again mimics the wider image that the hand has been taken from, a god-like figure determinedly reaching forward. In the same way, his close-up faces embody a whole scene, for example his composition of Einstein’s face is made up of a room in which an artist sits before a canvas showing the equation for the theory of relativity. The part represents the whole – from Einstein’s face we can then ‘recognise’ his context. This is the visual equivalent of Synecdoche, a literary technique of using a component of something as a symbol for the entire thing, for example when people refer to a car as ‘wheels’ (see more examples here). Adam’s hand, as such, microcosmically represents the whole image that people know as the Michelangelo’s Creation of Adam. The impression of the whole is the illusion, it is the observer that sees the ‘larger picture’ with sudden realisation, and it is Ocampo’s masterful arrangement of picture elements that gently guide the eye to this realisation.

Our new foiled journals feature some of Ocampo's stunning metamorphic artwork. Embossed and printed on foil, our products really bring these striking pieces to life. Take a look at the different designs we have here, here and here.

Our new foiled journals feature some of Ocampo's stunning metamorphic artwork. Embossed and printed on foil, our products really bring these striking pieces to life. Take a look at the different designs we have here, here and here.

If that's still not enough for you, we also have a lovely 2016 calendar featuring 12 of Octavio Ocampo's incredible paintings. It's available right now and you can check it out here.

Links

- Click here to learn about dream art and surrealism.

- Discover history's best optical illusions...

- Have a look here for a gallery of Octavio Ocampo’s work.