A French painter and graphic artist, Edgar Degas (1834–1917) was one of the leading members of the Impressionist circle.

Degas was not a typical Impressionist, having little enthusiasm for either landscape or plein-air painting but he was, nevertheless, extremely interested in capturing the spontaneity of a momentary image. Where most artists sought to present a well-constructed composition, Degas wanted his pictures to look like an uncomposed snapshot; he often showed figures from behind or bisected by the picture frame. Similarly, when using models, he tried to avoid aesthetic, classical poses, preferring to show them yawning, stretching or carrying out mundane tasks. These techniques are seen to best effect in Degas’ two favourite subjects: scenes from the ballet and horse-racing.

Early Studies & Influences

Originally destined for the law, Degas’ early artistic inspiration came from the Neoclassical painter Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres (1780–1867) – who taught him the value of sound draughtsmanshipy – and from his study of the old masters. However, he changed direction dramatically after a chance meeting with Édouard Manet (1832–83) in 1861. Manet introduced him to the Impressionist circle and, in spite of his somewhat aloof manner, Degas was welcomed into the group, participating in most of their shows.

A Traditional Education

Degas was born into a wealthy family in Paris, which is where the young man received his education. His father insisted that he attend law school, but Degas was uninspired and turned instead towards painting. He studied under a pupil of Ingres (Ingres himself would remain important to him throughout his career) for a short period and briefly enrolled in the École des Beaux-Arts, where he received a traditional artistic education that could have seen him progress as a history painter.

He painted several history pieces and exhibited at the Salon early in his career, but his diary, published in 1921, shows entries dating back to 1859 that list modern subjects he considered important to study. This shows the artist developing his unorthodox and unique approach at the same time as continuing his conventional education.

He travelled to Italy several times early in his career where he made copies of Old Masters – something that he continued to do later at the Louvre.

Cultural Influences

Degas had been brought up in similar social circles to Manet, and had enjoyed an early introduction to the arts, music, opera, literature and painting – his father was keen on music and the family home was frequented by musicians. Degas became friendly with Désiré Dihau (1833–1909), a bassoonist in the Opéra orchestra and probably through this friendship was given permission to sketch in the wings and orchestra pit of the Opéra. Degas was welcomed into the Dihau home, and it was here that he was introduced to Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec (1864–1901), who would become one of his greatest admirers.

Dihau’s portrait appears in several of the paintings Degas made of this subject. The Opéra was the perfect subject for a painter of modern life, as was the ballet, which Degas also famously painted. In Musicians in the Opéra Orchestra, 1868 he has taken a unique view of the scene, focusing on the musicians who are crowded in the foreground, while above their heads float the truncated and brilliantly lit bodies of the dancers.

Love of the Races

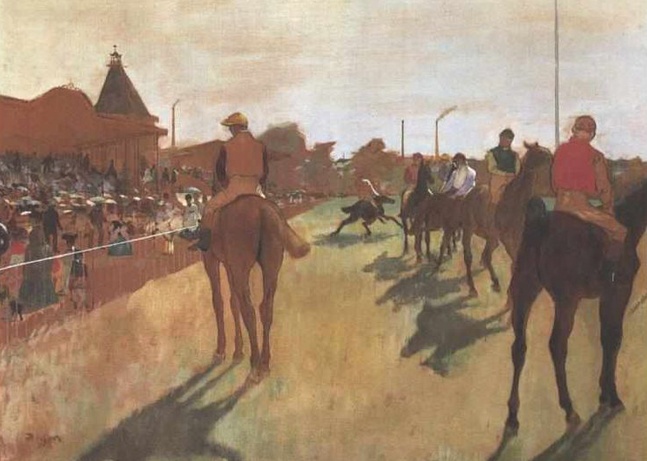

In 1861 he went to the races at Mesnil-Hubert with some friends and was immediately entranced. Horses became one of his few primary subjects, and the following year, in 1862, he began sketching scenes at the Parisian racetrack, Longchamps. Race Horses in Front of the Tribunes of around 1866–68 depicts one of his favourite moments, that of the tension before the start of the race. This was something that he frequently depicted, drawn by the excitement and restlessness of the horses and the crowds. He also characteristically cropped his scenes, providing an unusual view and implying that his painting was just a small part of a bigger event going on beyond the frame.

A Painter of Modern Life

By 1873 the idea that a group of artists could challenge the Salon and operate independently, bringing a progressive art with a new language to the public, had grown.

Société Anonyme des Artistes

Towards the end of the year discussions about forming an independent exhibitor’s association were rife and eventually, on 27 December 1873, the Société Anonyme des Artistes was registered. They held their first exhibition two weeks before the Salon opened in April 1874, and although well attended by the public, the financial handling of the Société was poor and by December of that year the members decided to disband it.

Degas, who was a founding member of the group, had by this time already made a name for himself as a painter of modern life. He focused his attention on people, turning to dancers, theatre and racecourses for his inspiration, and tackled his subjects with an unerringly honest eye. He concentrated on composition and the relation of his figures to each other, often incorporating unusual angles and truncated views that created ‘a moment of life’ sensation, much like a photograph.

Art Should ‘Precisely Render Life…’

In 1866, Jules and Edmond de Goncourt published their novel Manette Salomon, in which they propounded the idea that art should ‘precisely render life, embrace from close at hand the individual, the particular, a living, human, inward line…’. It was an approach based on the examination of modern life, and one that Charles Baudelaire (1821–67) had also addressed, but more significantly it was one that had great effect on Degas. The eccentric artist, who was already working in a highly original manner, strove to find new vehicles to express modern life, filling notebooks with his ideas about subjects to paint.

Subjects, Styles & Techniques

Unlike the other members of the original group, Degas painted primarily in the studio from memory and sketches rather than in front of the motif. He did not often paint landscapes and rarely, if ever, painted en plein air. Degas also chose to depict those subjects of modern life that had not been addressed before, such as tired laundresses, women bathing, his scenes from the racecourse and his famous ballet dancers.

Depicting Women

Increasingly Degas concentrated on just a few subjects that were gradually whittled down to images of women, their gesture and movement eventually eclipsing background details. He was interested in the juxtaposition of figures and their surroundings to create an oblique or truncated view, or one that created confusing perspective, raised questions and challenged the viewer.

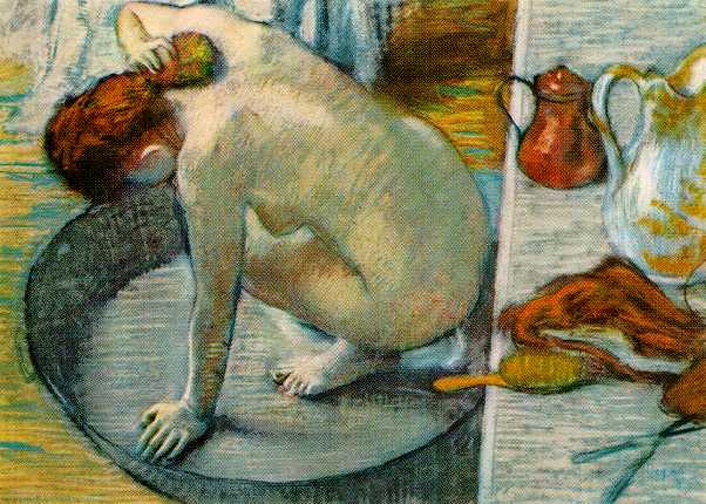

From around 1877 onwards Degas increasingly began to depict women washing and in various stages of undress. The women in his pictures, such as in Woman Washing Herself, 1886, are unaware of the viewer, which lends them a voyeuristic quality that has caused debate over Degas’s motivations and opinion of women ever since. These images, which he did in pastels, charcoal, oil and sculpted, were approached with an almost obsessive intensity, matched only by the vigour with which he depicted his ballet dancers.

In The Laundresseses, c. 1884–86 the honesty of his image and the candid depiction of women working recalls the spirit of the Barbizon artist Jean-François Millet (1814–75) and his paintings of labourers toiling. Degas has painted the women, seemingly unaware of his scrutiny, so they appear totally unaffected and natural in stance and attitude. It was an angle he took almost consistently, especially in his later works, and is one that evokes the sense of a photograph, a snapshot of mundane life. At this time great advances were being made in photography, something that Degas was aware of.

Degas’ Dancers

Degas’ Dancers

Degas increasingly isolated himself from his colleagues in the Impressionist circle from the late 1880s, and instead worked and lived in Paris, surrounded by just a few friends. He exhibited only once following 1886 and, struggling with his deteriorating eyesight, took up sculpting wax figures of ballet dancers and horses.

In these last years of his working life, his output consisted almost entirely of pastels and drawings (and wax figures) of dancers. The pastels allowed him to work more quickly and freely than oil paint, and gave his works a softness of outline that lent them an evocative, atmospheric feel. The pastel medium has a certain textured surface quality that creates a different sensation to paint – a sense of immediacy that is lost through the labour of oils.

Due to his failing sight, his works tended to become more vibrant in colour, with colour and surface texture becoming more important than preciseness of form. However his Green Dancers, 1900 shows an incredible lightness of touch, with the impressionistic rendering of the dancers’ skirts creating an astonishingly realistic image of the net and toile material.

Late Works

1886 was the year of the eighth and last Impressionist exhibition, though by this point the group had in terms of style and technique dramatically fragmented. It was also the year that the dealer Paul Durand-Ruel (1831–1922) staged the first exhibition in New York, showing works by Degas, Manet, Pierre-Auguste Renoir (1841–1919), Claude Monet (1840–1926) and other members of the group. Despite some criticism, overall they were well received across the Atlantic, and the American market looked set to be relatively favourable.

From the mid-1880s to the end of his life, Degas increasingly surrounded himself with his few close friends, the Rouart family, the model and artist Suzanne Valadon (1865–1938) and the sculptor Paul Albert Batholomé (1848–1928). He stayed in Paris but did not participate in the monthly gatherings at the Café Riche, which many of his contemporaries attended. After the last Impressionist exhibition Degas refrained from showing his work in public, with the exception of one small exhibition of a series of pastel landscapes in 1892.

By the 1890s Degas had changed his working practice and instead of producing a single picture he had started to work on series of related images. He would draw and sketch a succession of very similar works that formed a group of pictures, some as small as three different images, while others were as large as 30. Degas was also concentrating on his sculptural works, although he only ever exhibited one. After his death a host of models of dancers and horses, many of them damaged and crumbling away, were discovered in his studio.

If you've enjoyed reading about Impressionist painter and master of modern life Degas, then why not treat yourself to our sumptuous foiled journal, available here; or have a go at this jigsaw available here.

Links

- Find out more about MoMa's exhibition Edgar Degas: A Strange New Beauty.

- You can enjoy a vast array of Degas' artworks on this website.

- The Art Story website offers an in-depth look at Degas.