The American artist Edward Hopper (1882–1967) was a popular portrayer of atmospheric modern life, from his depictions of the isolated and pensive figures in the city to the quiet intensity and melancholy of his houses and seascapes.

Depicting America

The styles and influences that characterize twentieth-century American art are myriad. In no other period and, arguably, in no other country, were so many modes of expression experimented with, so many techniques used, or so many mediums exploited.

A Time of War

This was a time of unprecedented social change in the United States. The Civil War (1861–65) had changed the face of the nation, and the process of rebuilding and healing took decades. The first half of the twentieth century wreaked further havoc, as the First World War (1914–18) was followed by the nationwide Great Depression, instigated by the Wall Street Crash of 1929 and succeeded by the Dust Bowl of the 1930s. President Franklin D. Roosevelt’s New Deal promised new hope to a desperate people, but that hope was snatched away when the Japanese bombed Pearl Harbor in 1941, dragging America into a global war.

European Influences

European Influences

The changing face and fortunes of the United States were reflected contemporaneously and nostalgically in art throughout the twentieth century. As the nineteenth century drew to a close, European influences still held sway in the minds of many American artists. The works of the French Impressionists in particular inspired artists such as Mary Cassatt (1844–1926) and Childe Hassam (1859–1935), and for many, a sojourn in Europe, and especially Paris, art capital of the world, was essential for their artistic education.

Looking Closer to Home

Alongside this, though, artists like Charles Marion Russell (1864–1926) and Frederic Remington (1861–1909) looked to their own country and its history, painting romantic visions of the old American West. This rendering of a national identity, however nostalgic its roots, took a new shape as the century progressed. The fascination with European art changed as the continent was scarred by battle and Paris itself fell under occupation. While modern European styles such as Cubism showed their influence, American artists began to look to their own country for inspiration and subject-matter.

The New York-based Ashcan School began the trend for realist painting, and their depictions of everyday American life, without frills or ambiguity, spawned a later generation of modern Realist artists that included Edward Hopper and Charles Burchfield (1893–1967). An extension of this was Precisionism, a detailed, almost photographic style most evident in the works of artists such as Charles Sheeler (1883–1965).

A Portrayal of Modern America

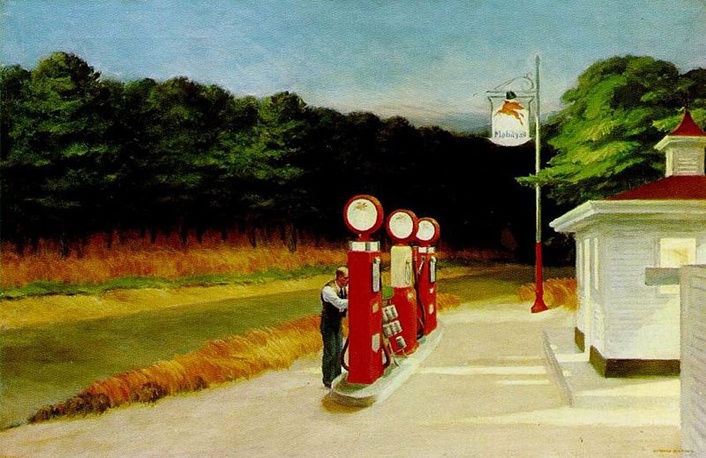

The terms ‘American Scene’ and ‘Regionalism’ are often used interchangeably and, from a technical point of view, this makes perfect sense. Some artists stayed aloof from what became an ideologically freighted Regionalism, however, and the American Scene description is better reserved for them. Hopper’s accounts of an everyday America are peculiarly unsettling. He shows a nation cut off from its productive countryside and from those wide-open spaces celebrated by the Regionalists.

Capturing a Sense of Isolation

Hopper’s figures frequently seem like spectres, making their way through the world like the living dead. Isolated, wrapped up in themselves, they come together in anonymous, transitional locations – motel rooms, diners, deserted offices – conversing without ever apparently making contact. Below are a few examples of Hopper’s artworks, which encapsulate his capacity to articulate a sense of loneliness.

Lighthouse at Two Lights

Edward Hopper spent almost his entire career living and working in New York. From 1912 onwards, however, he regularly travelled north to summer in Gloucester, Cape Cod and Monhegan Island, off the coast of Maine. In 1927 he bought his first motorcar and, from that point on, explored some of the more remote regions of Maine, spending several summers in a coastal resort known as Two Lights. Here Hopper painted the local sites, including Captain Upton’s House (1927) and the lighthouse positioned on a grass-covered promontory overlooking the ocean.

Hopper’s Lighthouse at Two Lights (1929) is painted from a low viewpoint, thus giving a sense of grandeur to what appears otherwise to be a rather squat structure. More importantly, he chose a very particular time of day – early morning, when the low sunlight cast long shadows across the landscape, modulating the forms of the lighthouse and silhouetting it against the sky. Hopper frequently depicted scenes at this quiet time of day, the stillness thus lending his images a sense of solitude and isolation.

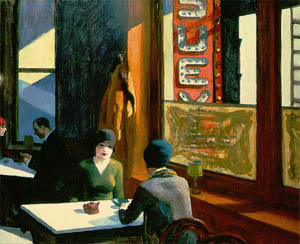

Chop Suey

Chop Suey

Hopper, perhaps more than any other artist, has captured the sense of loneliness and isolation that can only be experienced in the midst of a crowd in the modern city. His paintings, carefully constructed and composed to give the impression of a momentary glance – a voyeuristic gaze into the private space and emotions of an anonymous stranger – constitute a unique record of the changing sociology of modern America.

Chop Suey (1929) focuses upon two women seated at a restaurant table. Despite this company, however, each woman seems alone, lost in her own thoughts in a world of silence, while the couple in the background seem similarly uncommunicative. The high angle of view and the cropping of both the ‘Chop Suey’ sign, seen through the window, and the female customer on the left, all add a sense of strangeness and alienation to the scene.

Yet, for all its specifically American detail, Hopper’s work was highly influenced by nineteenth-century French painting. Here, Hopper explicitly refers to the café scenes of both Edgar Degas (1834–1917) and Édouard Manet (1832–83), while simultaneously updating and relocating them in modern America.

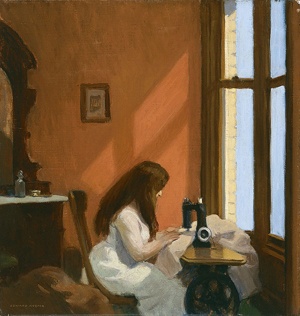

Summer in the City

Summer in the City (1932) presents two figures, a woman seated on the edge of a bed next to a naked man lying face down. Both inhabit a stark empty room devoid of any other furniture. No pictures adorn the plain walls and even the windows are positioned to allow the spectator no more than a partial view of rooftops and sky. Here only the contrast of light and shade generated by the sharply defined shadows falling across the room offers any relief to the monotonously plain interior.

Yet it is Hopper’s careful attentiveness to this monotony, to this visual inactivity, that reinforces the sense of isolation and alienation in the work. Who, we are bound to ask, are these two figures? Husband and wife? Lovers conducting an affair in a cheap, anonymous hotel room? And why do they sit in such physical proximity, yet convey such psychic distance from each other? Hopper offers us a tantalizing, voyeuristic glance at this mysterious, indefinable scene, but denies us any narrative closure.

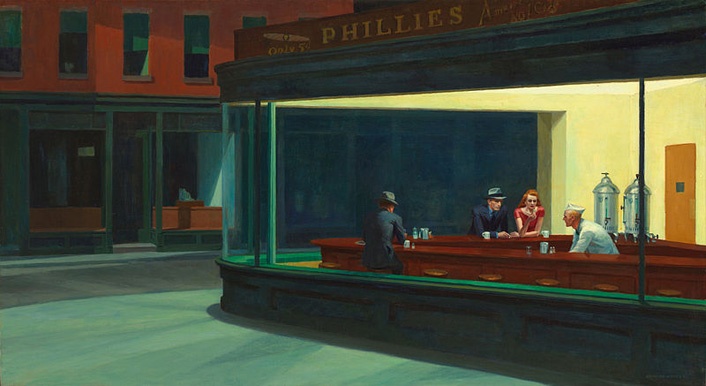

Nighthawks

Nighthawks is perhaps Edward Hopper’s most famous work. Produced in 1942, whilst the nation was at war, it depicts four figures, three customers and an employee, in a diner at night. In a typically Hopper manner, the narrative is obscure, the spectator remaining uncertain as to the relationship between the figures within, and indeed why he or she is situated on the empty street looking in.

Here Hopper has captured the effect of the artificial light flooding out from the diner and illuminating this nocturnal scene. He has also carefully plotted the position of each figure and the spaces between them so as to emphasize further the sense of isolation.

From preparatory drawings, it is evident that Hopper gradually shifted the viewpoint, from showing the diner straight on, as if from the opposite side of the street, to a more oblique angle. This shifted perspective, exaggerated still further in the final work, makes the spectator’s gaze more surreptitious, less confrontational, and thus adds greatly to the overall sense of mystery and alienation.

If you've been tantalised by what you've learnt about Hopper so far, you can find out more about him in our fantastic illustrated book Edward Hopper Masterpieces of Art. You can also buy a luxury journal with his haunting Nighthawks artwork beautifully foiled on the cover.

Links

- Austrian filmmaker Gustav Deutsch's film Shirley: Visions of Reality uses 13 of Edward Hopper's paintings to tell the story of a woman called Shirley. Watch the trailer here.

- Hopper’s wife, Jo, posed as his model for many paintings but was also an artist in her own right. Find out more about their relationship in this fascinating article.

- Get an insight into how Hopper created his masterpiece Nighthawks, by looking at his preparatory sketches for the piece, here.