The elegant figures and geometrical, bold designs of Romain de Tirtoff (1892–1990) – better known by the French pronunciation of his initials, Erté – are instantly recognisable and have left a lasting legacy in the art and fashion industries. Much of Erté's success stems from the sheer range of materials his works encompass, with his sinuous shapes and vibrant designs gracing not only magazine covers and book illustrations, but also jewellery, furniture, textiles, stage sets and costumes. Hailed as 'the father of Art Deco', the designer produced more than twenty thousand designs during his long life, and as a keen experimenter, he was growing in fame and continuing to sample new mediums for his art well into his nineties. Today we'll be taking a tour of the myriad forms his iconic, sleek designs took and how his eagerness to learn new techniques kept him and his work at the forefront of the design world.

Lifelong Learning

Beginning with work for Paul Poiret's studio in Paris, Erté's earliest illustrations were created using pen and indian ink. He also made extensive use of gouache, which he preferred over oils for the density, texture and consistency afforded by the pigments being bound together by glue. He used this medium predominantly for his major contract with New York's Harper's Bazaar, producing more than 200 magazine covers with this technique between 1915 and 1938. He was also employed as a designer of stage sets and costumes for music halls, ballets and operas – at age 86 he designed the sets and costumes for Strauss's and Hofmannsthal's comic-opera Der Rosenkavalier – and he even held the position of art director for a number of films. Erté greatly enjoyed learning new skills, and as he eagerly adapted to new techniques and media, he was able to build up a strong base of contacts in print and sculpture production and receive many commissions as a result.

He was learning new methods of graphic printing and jewellery design well into his later years, for example producing brooches and bronze sculptures based on his original designs, and undertaking a number of varied projects, from designing a playing card pack for a cigarette brand to experimenting with aluminium for costumes in a ballet called Metal. Embracing the development of printmaking techniques with enthusiasm, Erté later produced lithographs and serigraphs (silkscreen prints) of his work. Serigraphy, a higher quality method of reproduction than lithography, was especially useful for limited edition prints, and also allowed Erté to experiment – and set trends – with various techniques such as cut templates, additional embossed surfaces, built-up layers of colour pigment, and printing on black paper. He was able to continually rework earlier images in different mediums in this way, and in so doing create a 'collectors' market and give his works a combined sense of familiarity and newness.

Glamour and Ornament

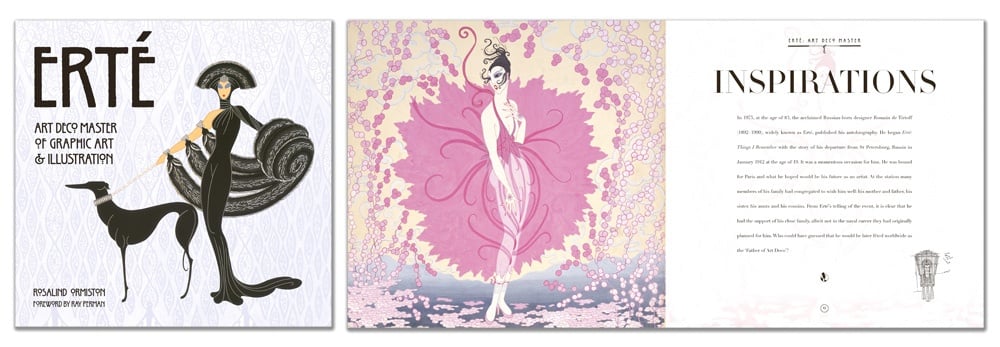

Erté's personal and professional interests from very early on lay in the theatrical, and he was greatly influenced by the extravagance of the stage, with the music, lighting and especially theatre costumes feeding into his work. His visual interpretations often involved beautifully draped clothes and sensuous figures adorned with fur and feathers, visual symbols that established the glamour and elegance of his iconic style. His ability to redesign original paintings into new forms – jewellery, costumes and sculptures – suggests he had the complete three dimensional aspect and potential in mind when producing any image, to the extent that he could translate between mediums with ease (useful when turning illustrations into real-life clothes for human bodies).

Erté was uninspired by male fashions of his day – in the later 1920s, he was the first designer to advocate a unisex fashion – and much preferred the artistry and extravagance possible with women's clothing and accessories. The women in his paintings were objects, but his objects were also women, fusing into the human form and vice versa with graceful fluidity. This is most noticeable, perhaps, in his Alphabet series, which he considered his most successful. There, as with numbers in his Numerals series, the human form and its accessories are twisted into the shapes of letters. His projects would usually in this way consist of a series, a 'suite' of related items all in the same medium, so that prints in the same album would be forming a narrative of some kind in a progressive movement forward.

If the alternative versions and inverse colours of his complementary images are anything to go by, it's clear that Erté liked variety, seeming to want to avoid being defined by any one particular type of work as well. Over a long career, his enthusiasm to explore new methods (for example learning to make bronze sculptures at age 87) kept his designs fresh and desired, making his work entirely suitable to the ever-changing 'a la mode' world of fashion, where his influence can still be felt today.

You can admire some of Erté's most beautiful work and find out more about his inspirations and techniques in our fantastic coffee-table book (ISBN: 9781783612161), available from our website here, or via Amazon.

Links

- If you'd like to know more about Erté's life, click here for our previous blog on the subject.

- The Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York hosted an Erté exhibition this year to mark twenty five years since his death. In case you missed it, here's a taster of what was on display.

- Take a look at Erté's fabulous Alphabet series here.