Surrealism was primarily a literary movement, dominated by writers and poets, and the definitions of its manifestos were intended to apply to writing more than to painting. The term was first used by the poet Apollinaire in 1917 to suggest a heightened sense of realism, but in Paris in the mid-1920s it came to designate a new art movement, whose influence was widespread and lasting.

Dadaism and Anti-Art

Artistic Anarchy

In the early twentieth century, the urgent need to liberate art from its past was nowhere more strongly felt than among the artists and writers associated with the Dada movement. The Dadaists reacted strongly against the generation of their parents and its associated morality, and responded to what they saw as the absurdity and mindless horror of the First World War. For them, the ‘end of art’ was already taken for granted: art had been discredited by its connection with the world of consumerism, and was the preserve of the ‘bourgeoisie’ – a past generation whose values were seen to be stifling and defunct.

Dada came into being in Zurich in 1916, with the name intended to be child-like and nonsensical. Dada was not a style but an attitude, central to which was the nonsense gesture, intended to turn the very idea of art on its head. In New York in 1917, Marcel Duchamp (1887–1968) presented for exhibition an upturned urinal that he entitled Fountain. This man-made object was rejected from the show, an outcome that was undoubtedly intended – in 2004, however, it was named as the most influential piece of modern art. Duchamp set about transforming perceptions of art, through ‘ready-mades’ like Fountain and interventions into famous paintings, like his addition of a moustache and an obscene caption to Leonardo da Vinci’s Mona Lisa. The sanctity of great works of art was rudely undercut by Dada – Duchamp also once suggested that a Rembrandt could be used as an ironing board.

Strange Juxtapositions

An emphasis on the absurd and the principle of random combinations was one of the means by which Dada artists responded to events in the wider world. In post-World War I Berlin, Dada took the form of a virulent political protest, as in the work of George Grosz (1893–1959), who produced drawings and paintings that brutally satirized figures of authority. In the hands of Hannah Höch (1889–1978) and John Heartfield (1891–1968), photomontage became a powerful tool for social commentary, for absurd and grotesque juxtapositions of words and images. Other key artists of the movement included Francis Picabia (1879–1953), Man Ray (1890–1976), and Jean Arp (1887–1966). Arp was a poet as well as an artist, and used words and sentences chosen at random from newspapers in his poetry, also producing compositions based on torn-up pieces of paper dropped in chance formations. Dadaists also held a very particular attitude towards modern technology: in contrast to the celebration of the machine that underpinned Futurism, Marcel Duchamp, along with Picabia, Man Ray and the German artist Max Ernst (1891–1976), produced works which ironized the new mechanized society.

Ernst studied psychology at Bonn University, taking a particular interest in the art of the insane. In 1919, he staged the first Dada exhibition in Cologne. Typically for this movement, visitors had to enter the show through a public urinal and were handed axes, in case they wished to destroy any of the exhibits. Ernst used a wide range of source materials in his paintings, drawings and collages, including illustrations from encyclopedias and engravings from technical manuals and sales catalogues, which he would juxtapose with other elements to create new and bizarre combinations. In his painting The Elephant Celebes (1921), a large metal corn bin is transformed into a grotesque imaginary creature.

Surrealism

Saying ‘Yes’ Where Dada Had Said ‘No’

Dada activities in Paris had fizzled out by 1922, and a group of young artists and writers led by the poet André Breton (1896–1966) had begun to search for a more positive means of expression. The former Dadaist Max Ernst settled in Paris in 1922, and his work was praised by Breton for the new poetic vision of reality it suggested. In order to try to stimulate new perspectives, Breton, Ernst and a group of writers including the poets Paul Eluard (1895–1952) and Louis Aragon (1897–1982) experimented with mind-altering drugs and hypnotic trances. In 1924 Breton produced the ‘First Surrealist Manifesto’, in which he set out a definition of Surrealist activity as ‘pure psychic automatism’, a way of thinking that would be completely free of ‘any control exercised by reason’, as well as ‘exempt from any aesthetic or moral concern’. As a kind of philosophical belief, Surrealism also set store by ‘the superior reality of certain forms of previously neglected associations’.

The Surrealists set out to produce ‘automatic writing’ – a free-flowing chain of thoughts and associations coming from the subconscious mind, inspired in part by treatments for psychiatric patients. Some members of the group questioned whether painting could ever be free of conscious control, as it was dependent on the artist’s technical and compositional intentions. However, some artists did produce work that was seen to be – to some degree – ‘automatic’.

Fresh Techniques

Fresh Techniques

Surrealist artists found ways of creating works that suggested the absence of a controlling rationality. André Masson (1896–1987) experimented with sand and paint poured on to the canvas, taking inspiration from the random forms which resulted. Ernst used the technique of ‘frottage’ (‘rubbing’), in which he took the patterns of wood graining, stones or leaves as a starting point to create pencil or wax crayon rubbings, which could then become the basis of mysterious compositions such as The Great Forest (1927). At the same time, he exploited the ‘poetic sparks’, which were created by the juxtaposition of totally unrelated objects.

Looking Within

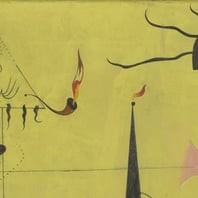

The Catalan artist Joan Miró (1893–1983) was introduced to the blossoming Surrealist group through Pablo Picasso (1881–1973). He joined the group in 1924, fascinated by the challenge of using art as a channel to the subconscious. From the mid-1920s, he began to fill his canvasses with biomorphic, semi-abstract forms, creating paintings using simplified marks and signs – schematic stick figures, body parts, animals and insects, suns and stars – combined with drawn lines and sometimes written inscriptions. These paintings, for example The Hunter (1923–24), had a child-like and spontaneous appearance, as if they were a more basic means of expression, freed from the limitations of a developed ‘civilized’ mentality.

The Surrealists also sought inspiration from the subconscious world that had been opened up by the writings of the Viennese psychoanalyst Sigmund Freud (1856–1939), and to the manifestation of this world in dreams and desires. The Surrealists were fascinated by the work of the Italian artist Giorgio de Chirico (1888–1978): they interpreted his paintings of deserted sunlit town squares with isolated statues, looming dark arcades and tall chimneys, such as The Enigma of a Day (1914), as full of hidden sexual symbolism. The dream-like atmosphere of de Chirico’s works also had a great influence on Surrealism, realistically painted and subtly disorienting the spectator through shifting points of perspective.

‘The Omnipotence of Dream’

The metaphysical paintings of De Chirico had a deep impact on the Spanish painter Salvador Dalí (1904–89), perhaps the most controversial member of the Surrealists. He studied at the Academy of Fine Arts in Madrid, until he was expelled, and in 1929 allied himself with the Surrealists. His relationship with the group was rarely smooth and, after several clashes with Breton, he was forced out of the group in 1939. In the interim, he produced some of the most memorable and hallucinatory images associated with the movement, describing them as ‘hand-painted dream photographs’. He produced works that suggested dream scenarios, and which explored his own sexual fantasies and fears. He used his own personal symbols to evoke taboo themes such as masturbation and castration anxiety: a hand swarming with ants; the sticky insides of an egg; a floppy extended limb supported by a crutch; and a snarling lion’s head to represent his feared father. Dalí’s oil paintings were meticulous in their use of illusionistic detail, a technique that was crucial to his development of what he called ‘paranoiac-critical’ activity, the cultivation of painted double images.

The paintings of the Belgian artist René Magritte (1898–1967) also took up the idea of art as an illusion. This great Surrealist master was initially influenced by Futurism and Cubism, before discovering the work of Giorgio de Chirico. He became a founder member of the Belgian Surrealist group in 1924, and went on to build his reputation for paintings of dreamlike incongruity, in which themes and objects are jumbled in bizarre, nonsensical situations, often showing paintings within paintings. He also explored contradictory combinations of images and words: The Key of Dreams (1930) depicted a series of objects including a hat, a shoe and a candle alongside handwritten labels that did not designate them at all.

New Ways of Seeing

Magritte used striking distortions of scale and bizarre juxtapositions (like a bottle becoming a carrot here), to force his viewers to question what they saw. The Surrealist ‘revolution’ in ways of seeing went beyond painting though, moving into the fields of photography, film and object-making, and the cultivation of new artistic techniques combined well with the emerging attitudes – based on an acceptance of unconscious desires – towards social morality. Surrealism was also a significant context for the development of the expressive distortions produced by Picasso in this period. The Surrealist leader André Breton had praised Picasso’s Cubist works as seminal precursors in their creation of a ‘window’ on to a new world.

One artist whose approach to Surrealism was markedly different from that of Dalí and the other main European exponents was the Chilian artist Roberto Matta (1911–2002). He initially trained as an architect, but when he took up painting in 1937 he was immediately attracted to Surrealism, and became one of the outstanding figures over the ensuing decade. His work had an enormous impact on the younger generation of American artists, and his technique of apparently random brushstrokes free from rational control influenced the era of Abstract Expressionist painters such as Arshile Gorky (1904–48) and Jackson Pollock (1912–1925).

Female Perspectives

Surrealism encouraged the exploration of personal, autobiographical events and feelings through disturbing images, which was a key feature of the work of the American painter Dorothea Tanning (1910–2012) and the Mexican Frida Kahlo (1907–58). Tanning’s earliest paintings drew on childhood nostalgia interpreted in a surreal manner, and this brought her to the attention of the American Surrealists. She married Max Ernst in 1946, and then worked in France as a painter, graphic artist and designer of theatrical sets and costumes. Tanning’s later work has a more fully rounded character but still essentially explores the female psyche and sexuality through the medium of dreams. Leonora Carrington (1917–2011), too, attempted to explore and analyse the female psyche through the medium of painting. She came under the influence of the Surrealists in the 1930s and produced a number of paintings that combined scenes and images from her childhood with mystical and fairytale themes, mingled with bizarre Surrealist elements.

Frida Kahlo, whose work André Breton described as ‘like a ribbon tied around a bomb’, endlessly explored pain and suffering in her art. Her canvasses verge on the surreal and often shock with their savage intensity. They evoke the anxieties and physical distress she experienced in her life, which included a tumultuous marriage to (and divorce from) the artist Diego Rivera (1886–1957) and a long convalescence from terrible injuries in a streetcar crash at the age of 15.

Another influential Surrealist figure, Meret Oppenheim (1913–1985) was introduced to Surrealism through Alberto Giacometti (1901–66) and Arp, even modelling at times for Man Ray. Oppenheim began contributing her own three-dimensional objects to the Surrealist exhibitions in 1933 and achieved critical acclaim three years later with Object, Fur Breakfast: a cup, saucer and teaspoon covered with gazelle fur. This typified much of her later work, in which ordinary, everyday objects were transformed into articles with fetishistic or sado-masochistic undertones. In her paintings and sculptures she explored female sexuality and woman’s role as a male sex object. On one occasion she even staged a banquet in which a nude female formed the centrepiece of the table decoration.

Watch out for our upcoming Dalí: Masterpieces of Art book, which will feature images of his greatest Surrealist creations. If you can’t wait that long, the brilliant illusionistic work of Octavio Ocampo’s is strongly reminiscent of Dalí’s visions: take a look at our journals of his work here, here and here.

For a more general look at Surrealism in the context of the development of Modern Art, take a look at our books Origins of Modern Art and The World's Great Masterpieces of Art, where you’ll be sure to find many of the key figures mentioned in this blog!

Links

– Check out our previous blog on Octavio Ocampo, Metamorphic Art and the Illusions at play in Dalí‘s work here.

– Learn more about Georgio de Chirico here.

– Have a look at these interesting facts about Magritte.

– For even more information on Surrealism, head over to The Art Lovers Guide to Surrealism.

Images in Order of Appearance:

Lobster Telephone, Salvador Dalí, image courtesy of Tate Gallery

The Elephant Celebes, Max Ernst, image courtesy of Tate Gallery

The Hunter, Joan Miró, image courtesy of The Museum of Modern Art

The Enigma of a Day, Georgio de Chirico, image courtesy of The Museum of Modern Art

Object, Fur Breakfast, Meret Oppenheim, image courtesy of The Museum of Modern Art