As explored in our previous Kandinsky blogpost, this is an artist who had a strong awareness of colour from an early age. This is brought out with great intensity in his later, more abstract paintings: the works that we now recognise most clearly as ‘Kandinsky’s’. Paintings like ‘Yellow, Red, Blue’ (1925) demonstrate the play of colour that Kandinsky used as a way of echoing, and influencing, emotions.

As explored in our previous Kandinsky blogpost, this is an artist who had a strong awareness of colour from an early age. This is brought out with great intensity in his later, more abstract paintings: the works that we now recognise most clearly as ‘Kandinsky’s’. Paintings like ‘Yellow, Red, Blue’ (1925) demonstrate the play of colour that Kandinsky used as a way of echoing, and influencing, emotions.

Wassily Kandinsky was concerned with communicating spiritual and emotional experiences, painting from that ‘inner necessity’ and using bold colours and vibrant shapes as vehicles for these truths. Colours, Kandinsky believed, were of value in themselves and worthy of being seen in isolation – but also in their relations with one another, with all their resonating tensions. ‘Tension’ is a word that crops up a lot in Kandinsky’s thoughts from this period, and he continually sought to bring out oppositions and dynamics through contrasting colours and forms.

So, following on from where we left off, this blog looks at Kandinsky’s developments in abstract art, as well as the difficulties his deeply spiritual expressions had in finding a place in both post-Revolution Communist Russia and the Nazi Germany that rose after the First World War.

The Quest for the Spiritual in Art

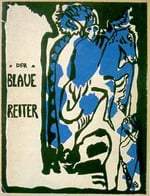

A landmark in Kandinsky’s artistic career was the creation of The Blue Rider Group, which held its first exhibition in 1911 and produced an almanac in 1912. This group of artists aimed ‘to awaken the ability to experience the spiritual in material and abstract things … to bring out this joyful ability in people who don’t have it.’ It was named after one of Kandinsky’s earliest paintings, ‘Der Blaue Reiter’ (The Blue Rider), which had embodied the romance of the search for the spiritual (Kandinsky associated the colour blue particularly with spirituality, as well as with the sky and heavens). Members of the group included Franz Marc, Gabriele Münter, August Macke, Paul Klee, Marianne von Werefkin, Clotilde von Derp, as well as one of the twentieth century’s most original and important composers, Arnold Schoenberg. As mentioned, Kandinsky felt a synonymy between vision and sound, between colours and music, and was fascinated by Schoenberg’s compositions. Along with picture plates and articles, the Blue Rider Almanac included musical scores, which, true to synaesthetic form, blended poetry and music. Kandinsky’s aim was to express the spiritual emotion through sensory experience – the surface sight and sound – so distinctions of medium did not really signify.

The Blue Rider Group necessarily dissolved in 1914 with the outbreak of the First World War. Kandinsky and Gabriele separated, and when Kandinsky was sent back to Russia he wrote vividly of the colours, ‘chords’, and ‘vibrations of the soul’ produced by the sunsets in Moscow. There, he married Nina Andreevskaya, and as Russia lurched first into revolution and then into the realities of Bolshevik rule, Kandinsky found himself increasingly marginalized. Soviet society was at first enthused with the ideal of bringing art, culture and ideas to the people, but over time the Communists scorned the individual and esoteric as ‘bourgeois’, and abstract art was seen as self-indulgent. Kandinsky returned to Germany in 1921, answering a summons from Walter Gropius, the founder and first director of Weimar’s Bauhaus.

Colours and Contrasts at the Bauhaus

Kandinsky’s time at the Bauhaus gave him the security and space he needed to develop his own aesthetic for a truly abstract art. The institution offered a completely new approach to construction and design, bringing form and function together. Kandinsky taught courses there in colour and in basic design, and he also gave classes in drawing and painting.

Aiming to realise feeling in the relationships recorded in his work, Kandinsky used the notion of contrast to create a sense of tension, believing that: ‘Content is nothing but the sum of organized tensions.’ As such, stark clashes of colour take centre-stage in works like White Zig-Zags, 1922, and oppositions animate his paintings from this period.

Kandinsky believed every colour had its own inherent character and meaning: Yellow was ‘brash and importunate’, and Green was ‘the most restful colour’. He felt that different combinations had very different effects on a viewer’s experience. As ever, synaesthetic identification of sight with sound fed his understanding, so that brown was able to ‘ring out a powerful inner harmony’. Moreover, Kandinsky believed that colours took on different characteristics when they were formed into different shapes. Triangles, for example, ‘sharp’ shapes, were particularly well adapted to ‘sharp’ colours, though as his work was often about confounding expectations too, he would combine sharp colours with soft shapes, and vice versa. Kandinsky always maintained that colours were for contrast rather than harmony, as he reasoned that for the unsteady modern age, ‘opposites and contradictions – this is our harmony.’ In this sense, Kandinsky saw his work as in its way representational.

Restlessly Innovative

The Bauhaus was not immune to the pressures of Weimar Germany, and it became a target with some of Kandinsky’s own works seized during a Nazi raid. After relocating twice, the Bauhaus closed in 1933, and Kandinsky moved to Paris with Nina. This was one of the most productive periods of his life, in which he experimented a little with materials, and came to recognise the character of the canvas too: no longer simply a blank surface to be worked on, he saw it as an actor in the drama of creation, with its own quivering identity: ‘crammed with thousands of undertone tensions and full of expectancy.’

When Hitler’s armies invaded France in 1940, Kandinsky fled with his wife, though soon returned and found that little fuss was made about his work – work which had been brandished ‘degenerate modern art’ just a few years earlier in Germany. Kandinsky’s period of artistic triumph had passed almost unnoticed by the wider artistic world. Towards the end of his life, he found success overseas instead. The American art connoisseur and collector Solomon Guggenheim was an important influence, and his interest in Kandinsky’s work attracted many young American artists to the paintings. This gave rise to Abstract Expressionism, though Kandinsky died in 1944 and never knew the scale and importance of this movement that he had inspired in post-war America.

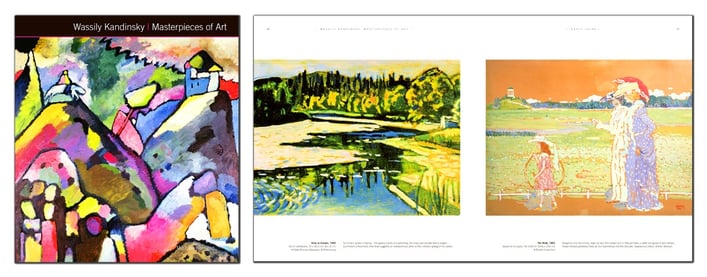

Kandinsky crossed boundaries, both artistically and literally, and in doing so created works that were essentially international in their abstraction – free of the particularities of place. In a letter to Gabriele Munter, in 1903, Kandinsky characterised himself as ‘constantly, chronically restless’, and it is this redevelopment, this movement, which his vibrant paintings embody. Get lost in the colours and shapes of Kandinsky’s masterpieces, and explore his work from the very beginning in our upcoming title Wassily Kandinsky: Masterpieces of Art (ISBN: 9781783612154). You can pre-order it on Amazon here.

LINKS

- Abstract Expressionism, the school that included Willem de Kooning, Jackson Pollock and Mark Rothko took its original inspiration from Kandinsky. Read more about it here.

- Have a listen to a famous piece by Kandinsky’s great friend and admired composer Arnold Schoenberg.

- How well do you know your colours? Check out this colour-matching game and test your reaction speed!