Cubism was one of the most influential twentieth-century art movements. Cubist works would provide a radical challenge to the painterly conventions for producing an illusion of depth, and they would attack the tradition of ‘high’ art by including within two-dimensional paintings and collages a range of extraneous materials not traditionally associated with high art, such as newspaper clippings, scraps of sheet music and stencilled lettering.

Picasso and Braque: Cubist Pioneers

Cubism flourished in Paris between 1907 and the outbreak of the First World War in 1914, and its impact was felt in artistic developments throughout Europe during this period. Two key artists who began to experiment with the Cubist style were French painter Georges Braque (1882–1963) and Spanish artist Pablo Picasso (1881–1973).

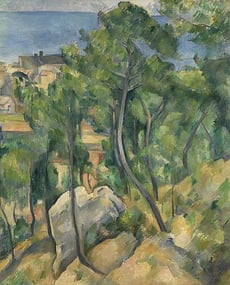

The Legacy of Cézanne

Braque had worked initially in a Fauvist style, but after seeing a major retrospective exhibition of the work of Paul Cézanne (1839–1906) in Paris in 1907, he pursued a new artistic vision. Cézanne’s work was an inspiration, particularly in its use of ‘passages’, the unification of parts of the picture surface through colour and tone, which meant that the difference between foreground and background was no longer sharply maintained. Braque made trips to the village of L’Estaque in southern France to paint the same sites depicted by Cézanne, and his resulting series of landscapes were exhibited in Paris in 1908, showing houses, trees and roads as simplified geometric forms squeezed into a shallow picture space. The box-like appearance of houses in these landscapes led the critic Vauxcelles – who had been quick to label the Fauves – to describe them mockingly as ‘cubes’, inspiring the term ‘Cubism’.

Les Demoiselles d’Avignon

In 1907 Braque had also made the acquaintance of Picasso, who that same year had produced his extraordinary large-scale painting Les Demoiselles d’Avignon. This work managed to bring together several radical and shocking elements. It showed five prostitutes with sharply distorted naked bodies within a room whose space seemed shattered into fragmentary shards, while the women’s faces derived from Egyptian, Iberian and African art, the latter still viewed as something crude and savage in this period. Picasso’s friends and collectors were unable to accept this painting, which they felt was ‘mad’ and ‘monstrous’, and it remained rolled up in his studio for almost 10 years. To the dizzying handling of space inspired by Cézanne’s landscapes, Picasso added a disregard for the European canonical treatment of the human body influenced by his interest in African art, preferring startling deformations and exaggerations to idealized proportions.

‘Analytical Cubism’

By the end of 1909, Picasso and Braque were close friends, and often painted together, producing works very similar in appearance. The period of ‘Analytical Cubism’, which lasted until 1912, saw the creation of paintings that took traditional motifs, such as still-life elements, landscapes and nudes, and broke these up into a series of facets, often incorporating fragmentary glimpses of an object or figure from different points of view. These motifs could sometimes become barely recognizable within an overall fluctuating mass of planes, painted in a limited colour palette of greys and browns, suggesting an emphasis on the conceptual process of coming to terms with the subject depicted.

The practice and problems of painting became the content and meaning of these Cubist works, where the central question was no longer what to represent, but how to represent it. The need to create an illusion of depth ceased to concern Picasso and Braque as painters; in fact they deliberately drew attention to the point that their explorations of objects in space were in themselves as paintings completely flat. In Pitcher and Violin (1909–10), Braque included a trompe-l’oeil nail at the top of the canvas, as if to suggest that the painting itself was simply tacked to the wall, and in 1911 he began to include stencilled lettering in his oil paintings. Picasso created the first Cubist collage in May 1912 when he included a piece of imitation chair-caning in a still-life of a table top. This fragment of oil cloth, painted to give the illusion of a chair seat, seemed to imply that all oil painting was a game, a means of fooling the spectator into believing what he or she sees.

‘Synthetic Cubism’

Cubist works after 1912 began to include pasted papers, textures such as sand and a greater range of colours – a phase known as ‘Synthetic Cubism’. If ‘analysis’ consisted in breaking objects down from their starting point in the real world, ‘synthesis’ meant that they were built up again from the basis of the simple geometrical forms of a piece of collaged paper or a block of colour. The Spanish-born Juan Gris (1887–1927), who came to Paris in 1906 and was strongly influenced by Picasso, produced synthetic Cubist works using a variety of colours and collage elements such as wallpaper and newspaper which were carefully cut and positioned, creating the impression of meticulous control over the objects depicted.

Picasso and Braque produced no manifesto, and in their later careers gave little explanation of their Cubist works. Many of their paintings and collages were small-scale, experimental works, which were not necessarily intended for public view. They did not exhibit during the Cubist period, relying instead on the support of the dealer Daniel-Henry Kahnweiler (1884–1979), who agreed to buy the whole of their output at fixed prices, giving them financial security and encouraging experimentation. But this private orientation did not mean that the Cubism of Picasso and Braque declined to engage with the outside world. In fact, their Cubist works are full of references to popular culture, to music hall, café life and advertisements. From 1912 to 1913, Picasso produced a series of pasted papers using newspaper clippings that referred to the Balkan Wars then raging in central Europe.

The Public Face of Cubism

Cubism did, however, have a public face in the form of the so-called ‘Salon Cubists’, a group of artists who exhibited together and whose leading figures, Jean Metzinger (1883–1956) and Albert Gleizes (1881–1953), produced a theoretical tract, On Cubism, in 1912.

The ‘Salon Cubists’

The group included the young Marcel Duchamp (1887–1968) along with his two older brothers, as well as Robert Delaunay (1885–1941) and Fernand Léger (1881–1955). Léger had learned from Cézanne’s distortions of pictorial space, and broke the forms in his paintings up into cylindrical geometrical shapes, which were dubbed ‘tubist’. In 1913 he began to produce a series of works entitled Contrasting Forms – lively compositions based on abstracted discs highlighted with primary colours: red, blue and yellow. These paintings were inspired by Léger’s interest in the shiny metallic forms of machines, and in the simplified designs on advertising billboards, both of which for him epitomized the dynamic potential of new, modern experience.

Orphism

Robert Delaunay and his wife Sonia Delaunay-Terk (1885–1979) also began to create paintings using circles and arcs of contrasting colour which aimed to capture effects of light and movement. Their work was based initially on scenes of modern city life, particularly the motif of the Eiffel Tower, but paintings such as Robert Delaunay’s 1912 Circular Forms relied less on recognizable subject matter, reflecting Sonia’s abstract designs for fabrics and book-bindings. Delaunay’s use of colour, as well as the Cubist handling of space, were both important inspiration for the Russian painter Marc Chagall (1887–1985), who lived in Paris between 1910 and 1914. Chagall combined these effects and modern motifs like the Eiffel Tower with subject matter drawn from his own upbringing to produce dream-like poetic paintings.

The poet Guillaume Apollinaire (1880–1918), a crucial supporter of modern art before the First World War, called the Delaunays’ work ‘Orphic’, a variant of Cubism which would rely on colour and form rather than subject matter for its meaning; the name was drawn from the ancient myth of Orpheus, who created a kind of ‘pure’ music. In his seminal collection of writings The Cubist Painters (1913), Apollinaire claimed: ‘We are moving towards an entirely new art which will stand, with respect to painting as envisaged up to now, as music stands to literature. It will be pure painting, just as music is pure literature.’ The painters of Orphism, who also included Francis Picabia (1879–1953), did not, however, produce purely abstract works: ‘pure painting’ should rather be understood as a desire to create works which had their own internal coherence independent of the motif represented, and which could convey some of the dynamism of modern experience that to these painters was much more important than the depiction of external reality.

If you've enjoyed learning about Cubism, you should check out our Origins of Modern Art book which puts it into the context of the changing art of the twentieth century, or The World's Great Masterpieces of Art book, which takes a fascinating look at many of the important art movements from the beginning of the twelfth century right through to contemporary art.

Links

- Cubism had clear influences on Futurism and Vorticism. For more on these art movements, see our blog here

- To delve further into the world of Cubism, take a look at the Tate's introduction to it here

- If you're feeling inspired by Picasso, you might like to visit his official Museum in Barcelona. You can find their website here