The Pre-Raphaelites were not afraid of social commentary in their work. From child labour to William Holman Hunt’s 1853 piece ‘The Awakening Conscience', which dealt with the problem of prostitution.Hunt, who had come up with the subject after reading Charles Dickens’ David Copperfield, said of it, ‘I arranged two figures to represent the woman recalling the memory of her childhood home, and breaking away from her gilded cage with a startled holy resolve, while her shallow companion still sings on, ignorantly intensifying her repentant purpose’.

Ford Madox Brown provided a commentary on the place of labour in contemporary society in his painting ‘Work’ (above) which shows a scene in Hampstead of a gang of men digging up a road, surrounded by the various layers of British society. There were many examples of this kind of social commentary in the Pre-Raphaelite’s work. They were a group unafraid to criticism the status quo and freely asked questions about the society around them, spreading their message through their art. These topics were covered all types of issues, one of which was the role of women.

In Victorian Britain, women were second-class citizens with rights similar to those of children. They did not have the right to vote, could not sue and were prohibited from owning property or possessing a bank account. Make up was frowned upon and clothing was not permitted to be tight, plus not an inch of flesh was to be shown. They were not allowed to work, unless as a teacher or domestic servant. Their role was, simply, to bear children and look after the house.

Women as the Victim

Prostitution was endemic in the towns and cities of Victorian Britain. Although prostitutes were regarded as unclean, it was considered natural for a man to want to use the services of a prostitute. Women destroyed by love – whether by false promises, tragic love or unrequited love – is a common theme in not just Pre-Raphaelite art but also in Victorian art in general. For the Pre-Raphaelites, however, the woman was often seen as the victim, a recurring motif, of course, of medieval romance. Generally speaking, in Victorian art the woman is depicted on her own - cast out into the world because of sexual transgressions for which she, not the man, is to blame. The Pre-Raphaelites often included the male in the picture – as was the case with Hunt’s 'The Awakening Conscience' – or at least made reference to his role in some way. She becomes, therefore, a person who has been wronged and the question is begged as to who is responsible.

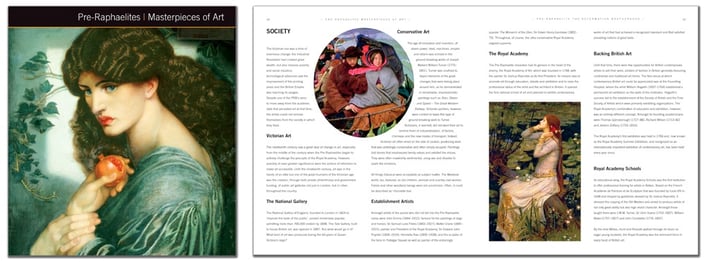

In Millais’ painting, ‘Mariana’, the female subject of the picture is shown stretching sensuously before a stained glass window, her hands somewhat provocatively on the back of her hips. The picture depicts a woman waiting in vain for her lover but Millais dispenses with the traditional representation of a woman grieving. She is separated from the natural world outside, the world of passion and human contact and the changing leaves outside her window and on the table in front of her suggest that she too is withering away as she waits longingly for his return. Thus, Millais presents Mariana to the viewer as a real woman with emotions and desires.

Discover more about Pre-Raphaelite art in our new art book Pre-Raphaelite Masterpieces of Art. To take a closer look at the book click here.

- To read more blog posts about the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood, click here.