In our previous blog on Mondrian, we learned about his early life and influences. We started exploring the path Mondrian took to get from strict Dutch traditional Impressionism to the abstract work we now know him for. If you missed our first instalment, check it out here.

In our previous blog on Mondrian, we learned about his early life and influences. We started exploring the path Mondrian took to get from strict Dutch traditional Impressionism to the abstract work we now know him for. If you missed our first instalment, check it out here.

Theosophy

Mondrian became a member of the Theosophy Association in 1909 and was part of the group for the remainder of his life. Theosophy became a great influence on him and his work as Mondrian began contemplating spirituality, its connection to the physical world, and the harmony that makes up the universe.

A Theosophical theory was that vertical elements represent the masculine while horizontal elements represent the feminine. It became important to Mondrian to balance these two elements and he started to simplify his work even further. He began by reducing his forms to oval shapes in vertical and horizontal lines and restricting his colour use. It was his attempt to get to the essence of everything through painting.

It was during this time that Mondrian began attracting some wealthy buyers. His almost completely abstract paintings of trees and churches sold well and he drew up a contract with a family of wealthy industrialists for 50 guilders a month for four small paintings a year.

In 1916 he moved to Laren, an artists' colony, where he met several artists who liked discussing new theories about art. One particularly influential acquaintance was Dr. Mathieu H.J. Schoenmaekers (1875–1944). Schoenmaekers philosophised about 'Christophosy' an offshoot of Theosophy. It united mystic and mathematical concepts. He wrote: 'the joint task of the artist and the mystic is to penetrate nature in such a way that the inner construction of reality is revealed to us.'

Schoenmaekers saw the vertical line as active and the horizontal line as passive. He also wrote about colour, saying that the primaries – red, yellow, and blue – are absolute, pure and represent the elements of the cosmos. This had a huge effect on Mondrian and his circle of friends, and became an important catalyst for Mondrian's development into abstraction.

Theo Van Doesburg, a huge influence and friend of Mondrian, wrote:

‘Mondrian realizes the importance of line. The line has almost become a work of art in itself; one cannot play with it when the representation of objects perceived was all-important. The white canvas is almost solemn. Each superfluous line, each wrongly placed line, any colour placed without veneration or care, can spoil everything – that is, the spiritual.’

Neo-Plasticism

Inspired by his friend, Van Doesburg, Mondrian wrote a lengthy essay on his theories of art called Neo-Plasticism in Painting. In the essay Mondrian explains how art is about balance and counterbalance in an effort to create harmony. He encourages artists and designers to reach for a universal mode of expression, or a visual language. It is the rectangle and the black, white and primary colours that make up the purest forms of expression.

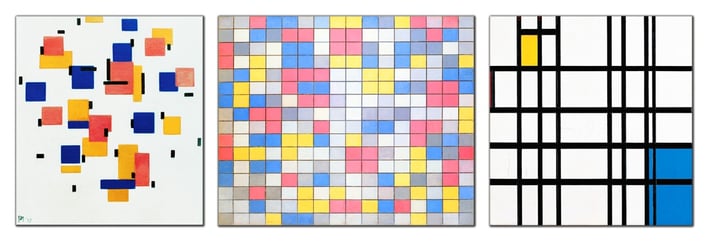

Mondrian began working on rectangular planes on white backgrounds. Combining Cubist, post-Cubist and his own Neo-Plastic ideas, he created Lozenge Composition with Grey Lines. The simple grid that focused on structure and balance became the framework for his future work.

His works became so pared down and radical that his previous patrons no longer wanted his work for their homes. Mondrian's style was now so different it was considered too radical for some contemporaries. After returning to Paris to see what new developments he had missed, Mondrian discovered that his own work had become more radical than anything in Paris.

Mondrian We Know Today

After finding his work too radical in Paris, Mondrian feared he would not be able to sell his work. He began to question his direction and contemplated giving up painting altogether. Mondrian wrote to Van Doesburg to declare his plans to retire, but his friend would not let him give up. An art collector and buyer of Mondrian's works helped him find clients to buy some of his paintings. Mondrian began painting flowers, like the ones from his earlier days, and sold them easily.

His spirits lifted and he reinvented himself, mingling with the Parisian art community. With a love of music and dance, Mondrian created a space for friends to come paint, dance, and discuss art.

By 1921 Mondrian had honed his style. His lines were bolder, his shapes more unequal, and his colour unevenly distributed. He focused on the nature of relationships in art, and expressed this through different sized and shaped planes. Each line was calculated, each colour deliberate. The whole painting was meant to represent harmony and balance.

The bold, abstract shapes and lines are a long way from the impressionist art he began with. Mondrian's style changed drastically over his life as he experimented with different interpretations and influences. He created his own style and became a major contributor to abstract and modern art.

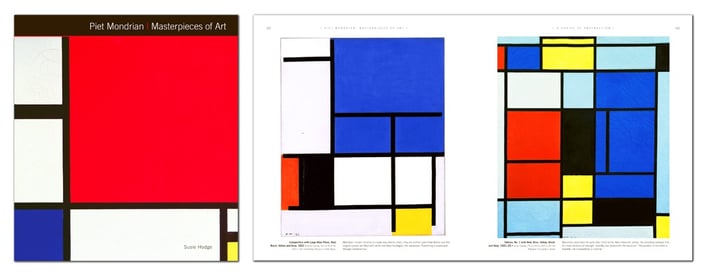

To read more about Mondrian, check out our book Piet Mondrian Masterpieces of Art (ISBN 9781783613557) here. Or on Amazon here.