Full Moon at Seba, c. 1837−42

In our last blog we talked about the origins of Japanese woodblocks and ukiyo art. We ended with the foundation of the Utagawa School, which was where Hiroshige, one of the greatest masters of woodblock art, took his first steps.

Andō Hiroshige was born in 1797 into the samurai class. When he was only twelve years old he succeeded his father as the fire warden at Edo Castle, and in 1811 he joined the Utagawa School under the tutelage of Toyohiro. Upon the latter’s death and although pupils would usually take their master’s name as their own, Hiroshige refused to be known as Toyohiro II. He wanted to build a reputation for himself, and he did not want that reputation to be associated with any other name than his own.

‘Thirty-Six Views of Mount Fuji’

In this he was indeed successful since his work is among the best known of the Edo period, alongside the landscapes of his contemporary Katsushika Hokusai. The woodblocks produced by Hiroshige and Hokusai can in fact to be considered as parts of the same whole since both artists drew inspiration from each other throughout their lives. Hiroshige even paid homage to the latter by giving his two series ‘Thirty-six Views of Mount Fuji’ the same name as Hokusai’s most celebrated collection of woodblocks. But while Hokusai’s work is most impressive in his technique and use of colours, Hiroshige manages to infuse life and movement into his landscapes, conjuring atmospheres with the tip of his brush. This feeling of a living, breathing nature is something that can be found in any of Hiroshige’s prints. He succeeded in making his ‘Thirty-six Views of Mount Fuji’ a rich collection of magical, dream-like images even though he used the same subject for all of them, and even though he produced two versions of the series. The first version was released in 1852 and is in landscape orientation, the second in 1858 in portrait orientation. Each print casts a new light on the surroundings of Mount Fuji: the purple mist over Edo Bridge and Nihan Bridge in the Eastern Capital shrouds the famous mountain in mystery while the untameable Sea off Satta in Suruga Province challenges anyone to dare to get closer.

Snow in the Precincts of the Temman Shrine at Kameido, 1831

‘One Hundred Famous Views of Edo’

The feeling is even stronger with his series ‘One Hundred Famous Views of Edo’ in which he offers a wide range of wonderful landscapes, from the sun rising over joyful decorations arranged for the Tanabata Festival in the city to a peaceful starry night on the Sumida River. His senses of colour and detail combine to make his 'Views' into windows, each one giving the onlooker a glimpse of another delicate and untainted world. Hiroshige even borders on the imaginary sometimes; in one of his ‘Famous Views of Edo’, he painted the Garment Nettle Tree at Oji bathed in an eerie, greenish light and surrounded by kitsune, white foxes straight out of Japanese folklore (at the time foxes were believed to be powerful, shape-shifting creatures and were sometimes treated as deities). These prints were among the last of Hiroshige’s. Although no one knows what the exact cause of his death was, he died during the cholera epidemic of 1858 two years after having decided to retire and become a Buddhist monk. But his legacy lived on: his daughter married two of his students one after the other and both took his name after he died (the first one as Hiroshige II, the second as Hiroshige III), although none of them came close to their master’s talent. Moreover, Japan’s isolation was coming to an end: in 1869, after the shogunate was defeated by the Imperial Court in the Boshin civil war, Emperor Mutsuhito allowed foreign trade to begin again.

The Meiji Period following the fall of Edo launched the process of modernization and industrialization in Japan and Japanese art became increasingly influential in Europe in the second half of the nineteenth century. From the 1870s all things Japanese became fashionable; Impressionist painters started producing pastiches of Japanese prints and Art Nouveau artists drew a lot of inspiration from ukiyo-e woodblocks. Alphonse Mucha’s The Flowers: Lily is a perfect example of that inspiration: its plain surfaces are alive with intense colour and its simple, elegant flowers seem to have been picked from Hokusai’s Lily Flower.

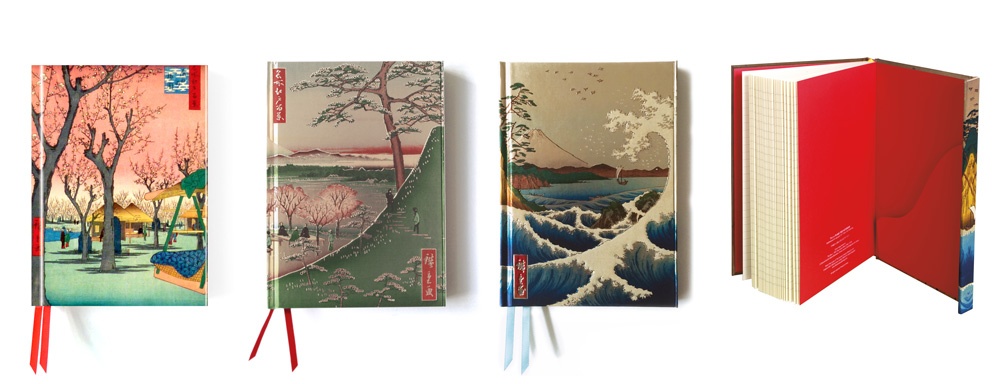

We're proud to feature Hiroshige's stunning work on several of our foiled journals. To take a closer look at the designs (going from left to right) click here, click here, or click here (BONUS: click here to see our new sketch book).

Links

- Read more about Japanese influences in European art in these articles here and here

- Find out why Impressionist painters were so excited about Hiroshige's work by clicking here

- For a guide to the complicated process of making woodblock prints we've got you covered

- Keep on learning about the astonishing legacy left by the ukiyo-e masters in this article on Hokusai’s Great Wave