Pop Art first emerged in the mid-1950s in both America and Britain. It was in part a reaction against the emotional seriousness and introspection of Abstract Expressionism, which had been affected by the experience of the Second World War. The term ‘Pop Art’ was coined in 1954 by the British-born critic and curator Lawrence Alloway (1926–90) to describe the ‘popular art’ and imagery produced by a mass culture that ‘high’ art had begun to pick up and use: flags, jukeboxes, badges, advertising logos, comic strips and magazines. After the intensity of Abstract Expressionism, Pop Art favoured irony and impersonal techniques in the creation of art works, as well as a return to figurative painting.

Bridging the Gap from Abstract Expressionism

A painterly style deriving from Abstract Expressionism was employed by a number of artists of the so-called ‘Beat generation’ of the 1950s. The work of Robert Rauschenberg (1925–2008) was influenced by the use of everyday, ‘found’ materials in Cubist collage and in the ‘ready-mades’ of Marcel Duchamp (1887–1968). From 1954, Rauschenberg began to produce works that were not only unusual in colour and surface treatment, but also incorporated scraps of ephemera and even three-dimensional objects such as stuffed birds, rusty metal, rubber tyres, pieces of discarded clothing and any old junk. In Bed (1955), Rauschenberg suspended a bed vertically on a wall and splashed it with coloured paint, a parody of the Abstract Expressionists’ ‘drip paintings’, suggesting that their ideas had been brought into the realm of the banal and the everyday. The ‘all-over’ effect created by Rauschenberg’s work, where no single element appeared compositionally more important than the others – whether painted, reproduced or found – was similar to the ‘all-over’ paintwork of Abstract Expressionism.

Jasper Johns (b. 1930), too, broke away from the work of the Abstract Expressionists, using subject matter that was common to everyone: familiar mass imagery such as flags and targets. In 1952 Johns settled in New York City, where he met Rauschenberg, who shared his views on the brash banality of contemporary culture. The influence of Dada is evident as he deliberately set himself against the tenets of conventional art. He eschewed originality by taking previously existing and immediately recognizable objects and emphasizing their very ordinariness. In works like Three Flags (1958), attention was drawn away from the subject represented, with its well-known forms and colours, towards the handling of the paint itself. Johns’s use of bold, iconic imagery was a crucial inspiration for the Pop artists.

Visual Communication

In the United States, John F. Kennedy’s presidency, which began in 1960, marked a new era of optimism and a celebration of middle-class consumer values. The world of advertising and graphic design was a major source for Pop Art. James Rosenquist (b. 1933) worked as a billboard painter before incorporating the large-scale, clear-cut forms and slick realism of advertising into his works. The painting F-111 (1965) put together a jumble of images from the mass media, including a jet bomber and a child’s smiling face, to suggest the jarring juxtapositions of modern urban life.

The visual image as a form of mass communication had superseded the written word and this was a key feature of the work of Roy Lichtenstein (1923–98) from about 1960. Lichtenstein’s paintings were composed of a series of tiny, meticulously painted ‘Ben Day’ dots – the basic components of printed imagery – and they depicted isolated comic-strip frames, often complete with words and captions. The painting Girl with Hair Ribbon (1965), for example, showed a glamorous blue-eyed blonde with an anxious expression, suggesting the small-scale mundane dramas of American suburban life.

The visual image as a form of mass communication had superseded the written word and this was a key feature of the work of Roy Lichtenstein (1923–98) from about 1960. Lichtenstein’s paintings were composed of a series of tiny, meticulously painted ‘Ben Day’ dots – the basic components of printed imagery – and they depicted isolated comic-strip frames, often complete with words and captions. The painting Girl with Hair Ribbon (1965), for example, showed a glamorous blue-eyed blonde with an anxious expression, suggesting the small-scale mundane dramas of American suburban life.

A Culture of Consumerism

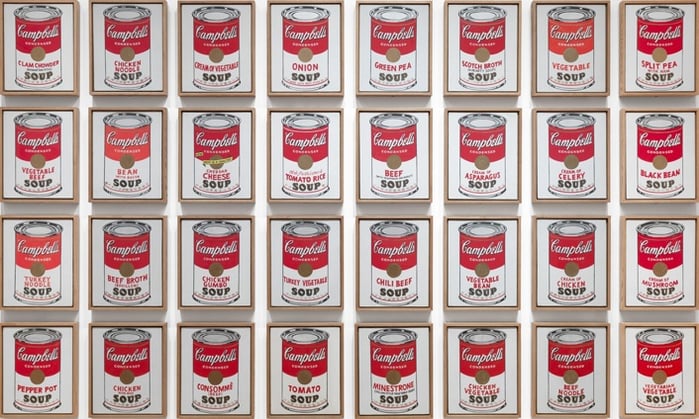

The American artist Andy Warhol (1928–87) first worked as an illustrator producing advertisements and fashion designs, creating in the early 1960s a series of stencilled paintings that depicted cans of Campbell’s tomato soup, dollar bills and Coca-Cola bottles. Like Johns, Warhol deliberately chose motifs that were part of a common American culture, and he developed a technique of screen-printing his images so that they could be mass reproduced. He used mechanical processes, with the aim to free the image from any connotations of craftsmanship, aesthetics or individuality – even describing his studio as ‘The Factory’. Warhol rapidly extended his references to popular culture by portraying famous personalities (Marilyn Monroe, Marlon Brando, Elvis Presley), as well as more sinister items, such as news clippings with car crashes or the electric chair. Such depictions suggested the superficiality of celebrity and media culture: his painting Marilyn Diptych (1962), created just after the film star’s death, evoked a melancholy sense of the inadequacy of the iconic image through the blurring and fading of Marilyn’s repeated face.

A stylistic neutrality and lack of emotion were important aspects of Warhol’s paintings, so that they maintained a deliberate distance from the realm of ‘fine’ or ‘high’ art. This interest in ‘low’ art forms as a means of rejuvenating artistic tradition had its precursors in American modern art in the work of earlier painters like Charles Demuth (1883–1935) and Stuart Davis (1894–1964). Demuth was one of the key figures in the American Precisionist movement, the main themes of which included industrialization and the modernization of the American landscape. His painting I Saw the Figure Five in Gold (1928), for example, had recalled the industrial look of mechanically produced billboard lettering.

British Pop Art

Pop Art in Britain as it developed in the early to mid-1950s expressed a desire for an American lifestyle of consumer plenty, in contrast to the atmosphere of post-war rationing and privation. In a collage entitled “Just what is it that makes today’s homes so different, so appealing?” (1956), the artist Richard Hamilton (1922–2011) presents an ironic, but also celebratory, homage to aspirational consumerism. The Scottish-born Eduardo Paolozzi (b. 1924) also drew upon popular American magazines, using a spicy women’s magazine called ‘Intimate Confessions’ in his early piece I Was a Rich Man’s Plaything (1947). Peter Blake (b. 1932) took inspiration above all from popular music, using collaged photographs, as evidenced in his album cover for the Beatles’ Sergeant Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band in 1967.

David Hockney (b. 1937) was an important mediator between British and American Pop Art. His early work drew upon popular culture, most notably in the form of graffiti. In Yorkshire, he exhibited at the Young Contemporaries exhibition of 1961, a landmark show that marked the arrival of British Pop Art. Hockney used simplified shapes – the horizontal forms of houses, lawns, hedges, pools and the blue Californian sky – in a series of works depicting the different movements of water, as in his painting A Bigger Splash (1967).

Art as Performance

The use of found objects and remnants of everyday life, as well as an ironic attitude towards the new consumer society, were features that Pop Art shared with the work of a group of artists in France in the 1960s known as the Nouveaux Réalistes. These artists wanted to involve contemporary society directly in their work through references to consumerism and the mass media. They experimented with performances and events, and with three-dimensional ‘assemblages’ based on the principle of collage. The artist Niki de Saint-Phalle (1930–2002) created a series of ‘shooting paintings’: large collections of assembled objects at which she and fellow artists would fire small cloth bags filled with paint, to produce a spattered, violent effect. The Anthropometries of Yves Klein (1928–62), who had no formal art training, were both literally figurative – a kind of portraiture of each individual body – and also abstract. The Italian artist Piero Manzoni (1933–63) met Klein in 1957, and under his influence moved away from figurative painting to the creation of plain canvasses enhanced with simple details such as a covering of white objects, which he called ‘Achromes’ (‘without colour’). He also slashed and stitched his canvasses to draw attention to them as objects in themselves. Manzoni took up the performative nature of art in his famous gestures of signing balloons filled with his own breath, and tins containing his own faeces.

Op Art and Abstraction

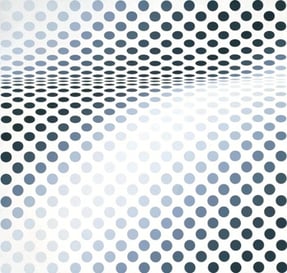

While Pop Art relied on recognizab le images to get across its celebration or parody of contemporary culture, the 1960s tendency known as ‘Op Art’ was uncompromisingly abstract. Op Art had its sources in Russian Constructivism and in the Suprematism of Malevich (1878–1935), in developing a painting style that was all about the spectator’s perception of abstract forms and about the sensations and illusions that these could provoke. ‘Op’ is a shortening of ‘optical’, and Op Art aimed to explore the effects of different kinds of retinal stimulation, using closely spaced black-and-white or coloured patterns. In line with other modern developments, Op Art sought not to provide the illusion of representation – one of painting’s traditional roles – but to make the viewer question their processes of seeing. Victor Vasarély’s (1908–97) coloured works, with their pulsating squares and circles, came to be seen as the epitome of Op Art. In Britain, Bridget Riley (b. 1931) also had a background in commercial design and advertising, going on to produce works like Burn (1964) – a composition in emulsion on hardboard, using repeated black-and-white triangles, which appear to fluctuate and move, disorienting the viewer. Influenced by the Futurists Giacomo Balla (1871–1958) and Umberto Boccioni (1882–1916), she began to develop this style in the 1960s, creating hallucinatory images consisting of endlessly repeated patterns.

le images to get across its celebration or parody of contemporary culture, the 1960s tendency known as ‘Op Art’ was uncompromisingly abstract. Op Art had its sources in Russian Constructivism and in the Suprematism of Malevich (1878–1935), in developing a painting style that was all about the spectator’s perception of abstract forms and about the sensations and illusions that these could provoke. ‘Op’ is a shortening of ‘optical’, and Op Art aimed to explore the effects of different kinds of retinal stimulation, using closely spaced black-and-white or coloured patterns. In line with other modern developments, Op Art sought not to provide the illusion of representation – one of painting’s traditional roles – but to make the viewer question their processes of seeing. Victor Vasarély’s (1908–97) coloured works, with their pulsating squares and circles, came to be seen as the epitome of Op Art. In Britain, Bridget Riley (b. 1931) also had a background in commercial design and advertising, going on to produce works like Burn (1964) – a composition in emulsion on hardboard, using repeated black-and-white triangles, which appear to fluctuate and move, disorienting the viewer. Influenced by the Futurists Giacomo Balla (1871–1958) and Umberto Boccioni (1882–1916), she began to develop this style in the 1960s, creating hallucinatory images consisting of endlessly repeated patterns.

Minimalism

Like Op Art, the Minimal Art of the late 1950s and early 1960s looked to earlier twentieth-century movements like Suprematism and the Neoplasticism of Mondrian (1872–1944) as precedents. It had in part evolved out of Abstract Expressionism, from the increasingly pared-down paintings of Barnett Newman (1905–70). Ad Reinhardt (1913–67) had been a close associate of the Abstract Expressionists, but partly through the inspiration of Indian art began to produce paintings using a single colour and simple symmetrical rectilinear forms. In a statement of 1962 entitled ‘Art as art’, Reinhardt claimed that the only aim of abstraction could be to make art ‘purer and emptier, more absolute and more exclusive’. Minimalism sought to eliminate all self-expression from art, creating works that were meaningful in their own right without representing anything, and that were conceived in the artist’s mind rather than found in nature. For example, the work Harvest (1965) by the painter Agnes Martin (1912–2004) consisted of a fine grid of thousands of criss-crossing pencil lines on a plain cream canvas – intended as a geometric work that was emotionless and impersonal.

Conceptual Art

The representation and incorporation of real objects in Jasper Johns’s paintings, and his sculptures of beer cans and flashlights in real-life scale and detail, raised the issue of art as a process of thought, making Johns an important forerunner of Conceptual Art. Both Pop artists and Mimimalists had been concerned to some degree with art as a means of thinking – ‘art as idea’ – which could go beyond the boundaries of the traditional media of painting, drawing and sculpture to include gestures, performances and happenings. The common starting point of these different manifestations was the rejection of the conventional art object: something tangible and unique that could be exhibited and sold. The work of Marcel Duchamp in the 1910s was a crucial inspiration for this, through his designation of objects – a bicycle wheel, a bottle rack and a row of coat pegs – as well as transactions – a cheque for his dentist, a bond for a roulette game – as ‘art’. The Conceptual Art of Roman Opalka (1931–2011), for example, included an extensive series of paintings called 1 to Infinity, in which canvasses were filled with infinite sequences of numbers, each one recorded into a tape player at the same time as it was painted.

Conceptual Art, an international movement bridging the 1960s and 1970s, often resulted in events and activities that were short-lived, existing for posterity only in the form of photographs, film or written documentation. However, painting was also used by Conceptual artists to raise questions in the mind of the observer, whose role now became more important than ever by participating in and ‘completing’ the work of art. A shift of emphasis away from the art object itself and towards a set of ideas about the role and function of art led to the frequent use of language as an integral part of an art work. The artist Ben Vautier (b. 1935) painted bold slogans in acrylic on canvas that were intended as a kind of anti-establishment propaganda, as with the painting Art is Useless, Go Home (1971), a playful and provocative piece that transforms painting into a paradoxical ‘anti-art’ activity. Conceptual Art was often austere and unrelenting in its appearance and its attitude towards artistic tradition, seen as ideologically loaded and unacceptable. The movement began to fade in the mid-1970s, when artists began to take a renewed interest in painting’s materials and subject matter. It had, however, brought to the fore the use of irony, humour and autobiographical content which would all be taken up by new generations of artists.

If you've enjoyed our series of blogs on Art Movements, then be sure to have a look at our book on The World's Great Masterpieces of Art, which covers an impressive selection of the key artworks from each movement. Also: Pop Art, Op Art, Minimalism and Conceptual Art were all inspired in part by earlier influential ideas, which you can read more about in our book Origins of Modern Art.

Links

– Find out more about Jasper Johns in this essay from the Met Museum.

– Watch a video interview with one of Yves Klein's 'Anthropometries' models here.

– Discover a little of the science behind Op Art here.

Images in Order of Appearance:

– Campbell’s Soup Cans (1962), Andy Warhol, © 2016 Andy Warhol Foundation / ARS, NY / TM Licensed by Campbell's Soup Co. All rights reserved, via Museum of Modern Art

– Bed (1955), Robert Rauschenberg, © 2016 Robert Rauschenberg Foundation/Licensed by VAGA, New York, NY via Museum of Modern Art

– Girl with Hair Ribbon (1965), Roy Lichtenstein, via Modern American

– A Bigger Splash (1967), David Hockney, © David Hockney, via Tate Gallery

– Hesitate (1964), Bridget Riley, © Bridget Riley 2015. All rights reserved, courtesy Karsten Schubert, London, via Tate Gallery

– Three Flags (1958), Jasper Johns © Jasper Johns/Licensed by VAGA, New York, NY via Whitney Museum of American Art