One of the most wide-reaching and influential art movements of the 20th century, the Arts and Crafts movement has had a significant impact on how we perceive design.

One of the most wide-reaching and influential art movements of the 20th century, the Arts and Crafts movement has had a significant impact on how we perceive design.

Founded in 1880, the movement brought together like-minded creators from around the world. This resulted in a wide array of works within the movement, whilst their individual aesthetics could vary wildly.

The first president of the Arts and Crafts Exhibition Society (created in 1887), was Walter Crane. He was an illustrator and artist, but more importantly he sought to ‘give opportunity to the designer and craftsman to exhibit their work to the public for its artistic interest and thus to assert the claims of decorative art and handicraft to attention equally with the painter of easel pictures’.

Though the society floundered at first, in part due to the publics very clear distinction between 'fine' and 'decorative' art, its fortunes were reversed after William Morris took over the presidency in 1891.

Due to this, Morris is often seen as the founding father of the Arts and Crafts Movement. However, in truth he was only one of a small group of people in the mid-nineteenth century who were appalled at the lack of good design practice. For them, the Industrial Revolution had corrupted sensibilities. Mass production of many items such as furniture and housewares had been ill conceived, shoddily made and often over-decorated for no purpose other than effect.

That said, before we learn more about Morris we must first discuss two other figures...

John Ruskin and A.W.N. Pugin

By the mid-nineteenth century Ruskin had already established himself as a well-respected writer - as an apologist for the artist J.M.W. Turner and the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood of artists.

Prior to Ruskin’s essays on design and aesthetics, an English architect, designer and polemicist, Augustus Welby Northmore Pugin, had already written to demonstrate how classical architecture was inappropriate to a Christian country such as England, since its origins were in the pagan ancient worlds of Athens and Rome. In short, Pugin advocated a return to the medieval forms of craftsmanship and a ‘truth to materials’, central tenets of the later Arts and Crafts Movement.

(Pugin died at the age of 40, exhausted by the sheer output of his work. Not only did he design churches and all of their elaborate interiors but also many of the accoutrements of church life, such as the priests, vestments and Eucharistic objects. His most celebrated work is the interiors of the Houses of Parliament, London)

Building on Pugin’s ideas, Ruskin himself stopped short of a return to a medieval society, which he considered feudal and inappropriate to modern Victorian Britain. Like Pugin, however, Ruskin saw Gothic as the only authentic style for Britain - despite his own tastes being more eclectic.

Ruskin expressed his social ideas in the form of monthly pamphlets under the title Fors Clavigera, beginning in 1871. Although specifically intended to be read by the working classes, an enthusiast for these and other Ruskin works was William Morris.

William Morris

Morris studied theology at the University of Oxford with the view of becoming a clergyman, but instead became enamoured of an artistic life after attending some of Ruskin’s lectures and seeing at first hand the naturalism he advocated in the paintings of the Pre-Raphaelites.

Morris had also become disillusioned with the church and its lack of vibrancy. He visited many ancient churches and was appalled at the lack of maintenance and/or inappropriate refurbishment of their fabric and interiors. Morris vowed to arrest this problem and later set up the Society for the Protection of Ancient Buildings (SPAB), in 1877. It was Burne-Jones who introduced Morris to the Pre-Raphaelite artist Dante Gabriel Rossetti.

Dante Gabriel Rossetti

Rossetti was one of the founders of the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood, along with John Everett Millais and William Holman Hunt. The Brotherhood was established in 1848 to reverse the mode of painting that had become ‘mannered’ since the sixteenth century, following the death of Raphael. They felt that this style of painting was ‘sloshy’ and lax, and advocated a return to more naturalistic forms by referring to nature for inspiration. In this regard they were supported by Ruskin, who told them to ‘follow nature’, wrote supportive articles about them and their aims, and purchased their work.

All three Pre-Raphaelite artists were initially drawn to the romanticism of medieval culture and also enjoyed reinterpreting biblical narratives whilst using more natural contemporary models. In this morally righteous Victorian era, many of the pictures were seen as scandalous and even blasphemous since they depicted Holy figures in an informal setting.

William Morris was drawn to the charismatic Rossetti when they met in 1856, at a time when the artist had moved away from the ideals of his ‘Brothers’ in favour of a more spiritual dimension to his work. He encouraged Morris to take up painting himself; a venture that was very short lived. In the following year, Rossetti introduced Burne-Jones and Morris to his friend, the architect Benjamin Woodward (1816–61), who had recently completed the construction of the Debating Hall at the Oxford Union and asked them to decorate the interior with medieval-style frescoes.

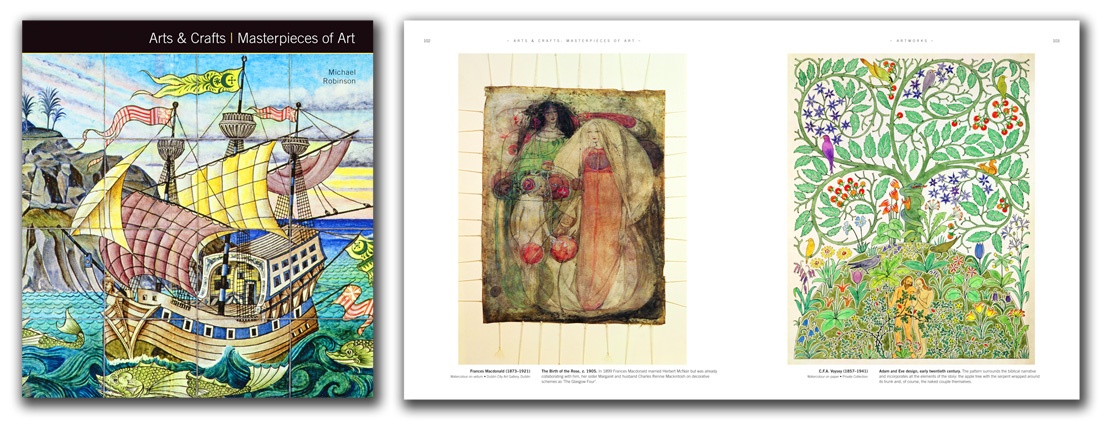

This article is a heavily truncated extract of text from our new book Arts & Crafts: Masterpieces of Art. Take a closer look on our wesbite here, or take a look on Amazon.