Some of the most visually stunning works of art have been painted directly onto walls and ceilings. The amount of time and effort that must have gone into these pieces is reflected today in the care taken to preserve them. Understanding the history and method behind this technique can help us appreciate it even more.

Ancient Beginnings

Paintings dated to around 3,000 BC were used to decorate the walls of tombs and temples. Paint was probably also applied to the murals in palaces and villas as well, but none has survived. Like the earlier cave paintings, tomb-paintings survived because they were not exposed to sunlight or weather. Similar paintings have been recorded in the Minoan civilization of Cyprus at a slightly later date and the same techniques continued through the Classical periods of Greece and Rome.

Early Practice

The technique invented by the Egyptians and perfected by later civilizations is known as fresco (the Italian word for ‘fresh’). It may be defined as painting on wet lime plaster using pigments mixed with water and lime. As the water evaporates, the setting of the lime binds the pigment to the plaster. The process is completed by chemical reaction: exposure to the air converts the lime to carbonate of lime and this has the effect of fixing the pigment, just as if the painting on piece of pottery was glazed and fixed by firing in a kiln.

Colours and Materials

The pigments used by the earliest Egyptians were basically the same as those used by the prehistoric cave-dwellers, but gradually the range has extended to include ochre (reds and browns) and malachite (greens and blues). These minerals were ground to a very fine powder and mixed with water and lime, but the Greeks, and possibly also the Minoans of Knossos, gave body to their painting materials by adding egg yolk, size, gum arabic or beeswax.

Rome

The earliest written account of the technique of fresco painting was given by Vitruvius, who stated that the Romans borrowed the practice from the Greeks. Immense care was taken in the preparation of Roman plaster, which was several inches thick. The basis was composed of the arriccio, a mixture of rumbled bricks, sand and lime, on top of which were several layers of lime and powdered marble, progressively finer and smoother and carefully applied with a trowel to create a highly polished surface. It has been argued that only the ground colouring was applied in a mixture of pigment and lime water, and that the final painting was executed in an emulsion, but it is impossible to say for certain.

Roman painters also used a technique whereby colours with a wax base were applied by some kind of heat treatment, and there is some evidence to suggest that this refinement was used to create the astonishingly colourful frescoes at Pompeii. This technique, however, seems to have been uncommon, and when fresco-painting was revived at Rome in the thirteenth century the usual method was either to apply the paint to the still-wet plaster or to dampen dry plaster immediately prior to painting. Whichever was the case, there was no way in which frescoes could be repainted and there was no margin for error on the part of the painter.

Cartoons

This method of painting continued more or less unchanged until the fifteenth century and the great era of ecclesiastical decoration. By that time the Italian painters were distinguishing between fresco secco, the art of painting in watercolours on dry plaster, and buon fresco, the more traditional technique of mixing pigments with lime and water applied to fresh wet plaster. Because of the haste with which the painter had to work, he would plan the exact design in pencil on paper or parchment as a preliminary cartoon (from the Italian cartone, literally ‘a little card’) – long before this term took on the more specialized meaning of a satirical drawing. The cartoon was often overlaid with grid lines, corresponding, on a larger scale, to a pencil drawing on the plaster itself, known as the sinopia (from the Greek synopsis, meaning ‘overview’).

Larger Murals

In the case of large murals a thin layer of wet plaster (intonaco) was applied to an area sufficient for each day’s painting, working from the top left-hand corner to the bottom right-hand corner, in daily sections known as giornate. Whatever portion remained unpainted at the end of the day was carefully scraped away and the edges undercut, the process being repeated the following day. A careful examination of late medieval frescoes will often reveal the joins in the plasterwork. Buon fresco might be used for the principal subjects. Such features as the texture of clothing, hair and fur could be suggested with the point of a very fine hard brush.

Pigments

Treatises on painting dating from the fifteenth century give various recipes for both lime and the mixture of pigments. The exact proportions of lime and sand (a ratio of 1:2) were just as important as the preparation of the lime itself, which could take years to mature correctly. White colouring was known as bianco sangiovanni (‘St John’s white’) and was produced from little cakes of slaked lime exposed to air and sunlight for several months. To the basic pigments of the ancients, the Italians added raw or burnt sienna, terra verte, metallic oxides such as chrome yellow and the cobalt blues and greens.

The Germans invented smalt (Schmalte), a deep blue pigment which revolutionized the appearance of stained glass and enamels, but which was also adapted to fresco painting. Previously the Italians had obtained this colour from ground azurite, which tended to turn green with exposure to the atmosphere and the carbonic acid in the lime. This chemical reaction was countered to some extent by mixing the powdered azurite with egg-yolk, but to achieve a true deep-blue effect only ultramarine (an expensive substance produced by grinding lapis lazuli) would suffice. Fresco painting has been revived in recent times; notable exponents include the Italian José Clemente Orozco (1883–1949) and the Mexican muralist Francesco Clemente (b. 1952).

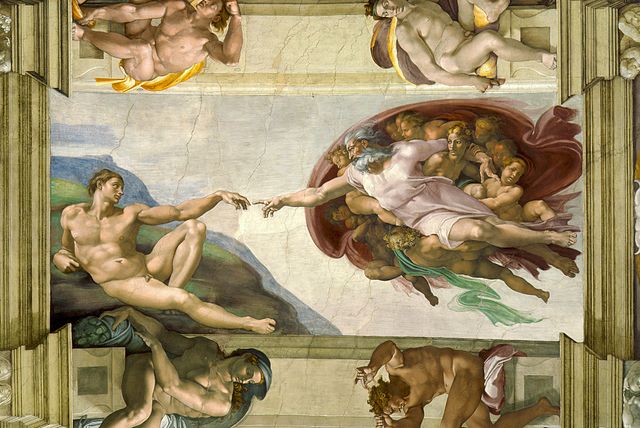

If you want to learn more about techniques and styles, our book How to Paint Made Easy comes out at the end of the month and can provide wonderful insight on how to get started on creating beautiful paintings. Alternatively, if you'd like to see more fresco artworks, our Michelangelo Masterpieces of Art book delves into his life and works, including stunning images of his frescoes in the Sistine Chapel and the Pauline Chapel.

Links

- The Tate has some more information on frescoes here

- Further information on fresco artists and works can be found here

- Read more about Renaissance art here

Check out all of the Painting Techniques blog posts!

- Painting Techniques | 1 | Perspective

- Painting Techniques | 2 | Watercolour

- Painting Techniques | 3 | Fresco

- Painting Techniques | 4 | Tempera

- Painting Techniques | 5 | Pastel